New media of all times

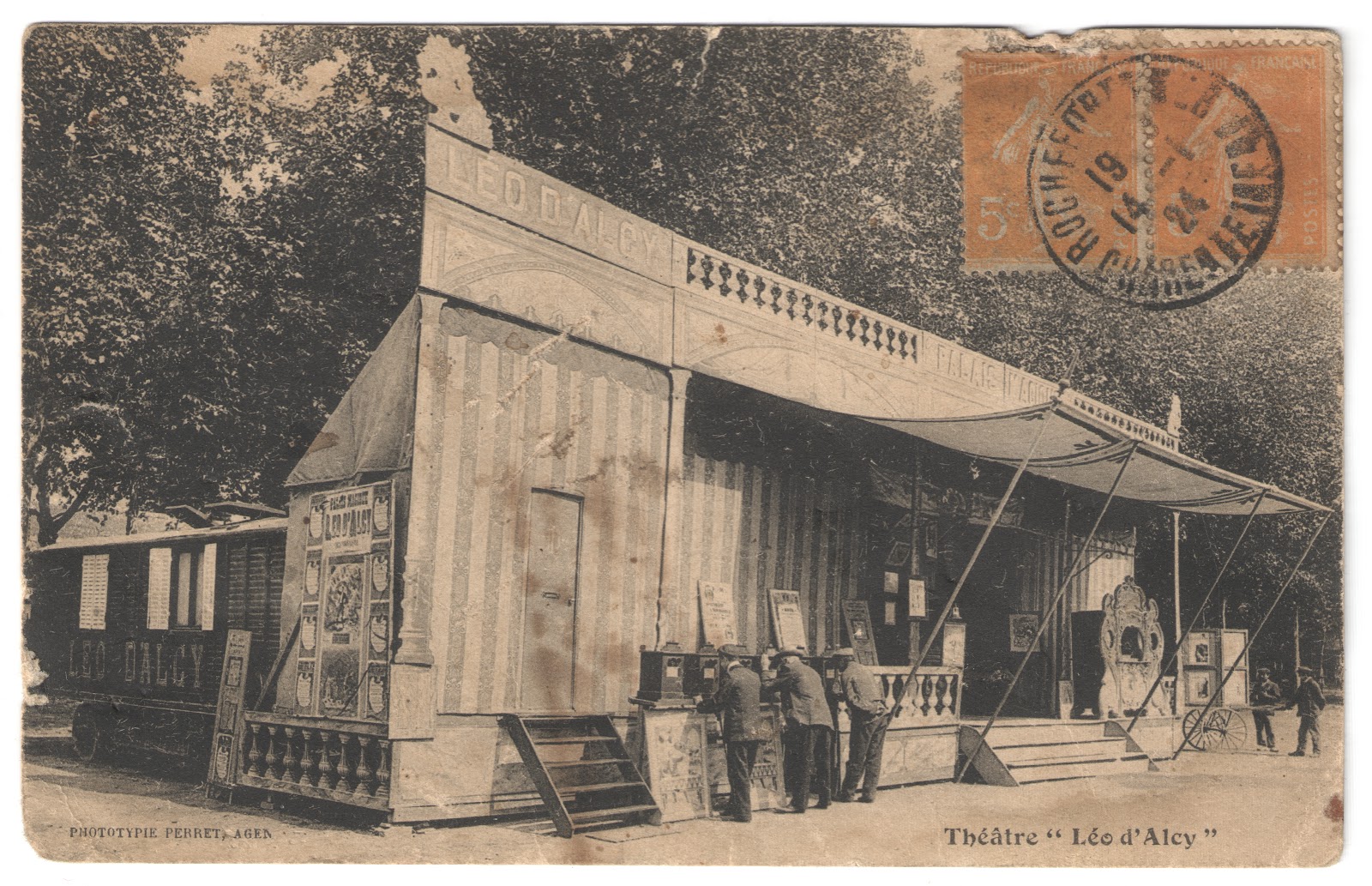

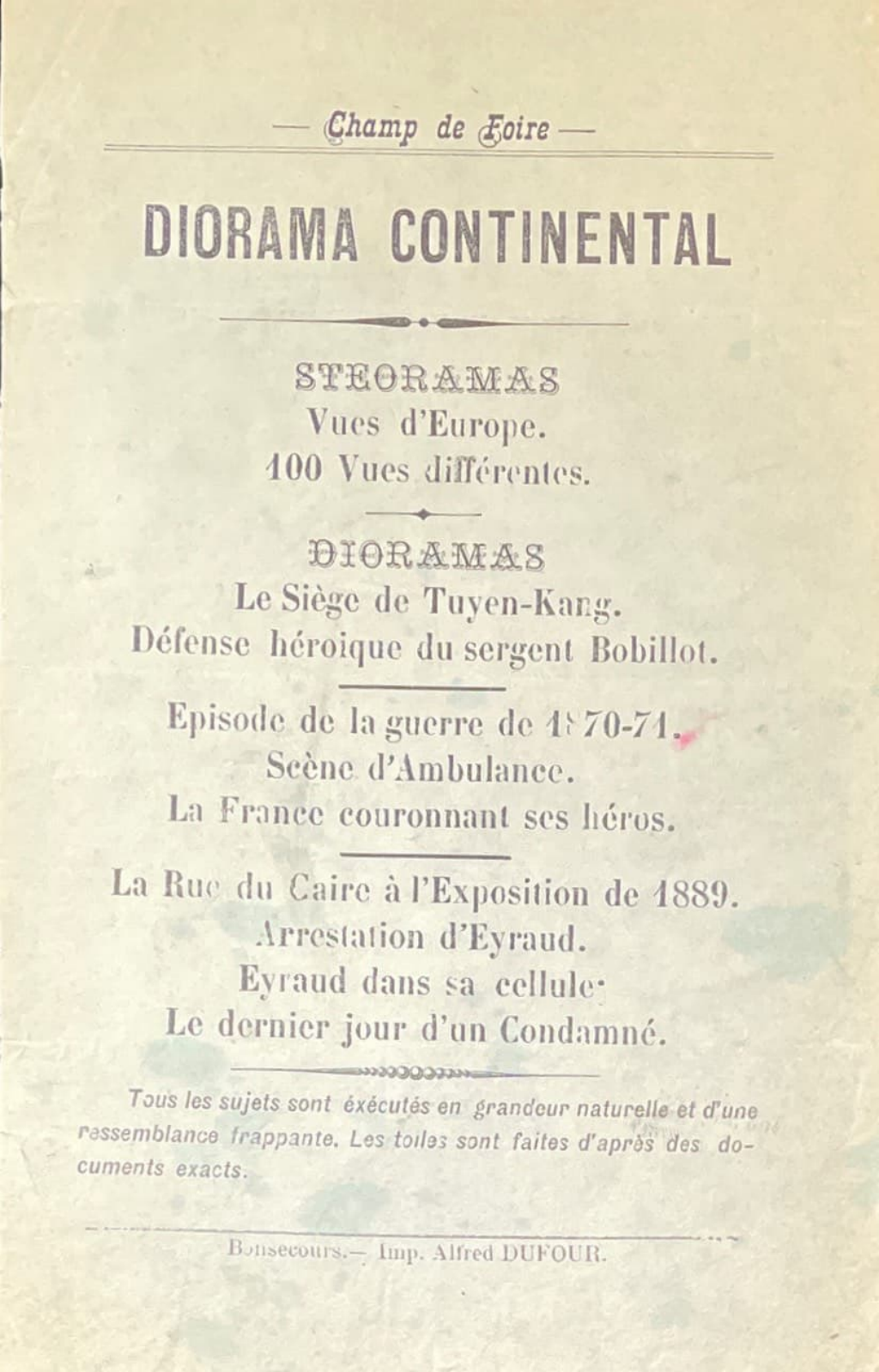

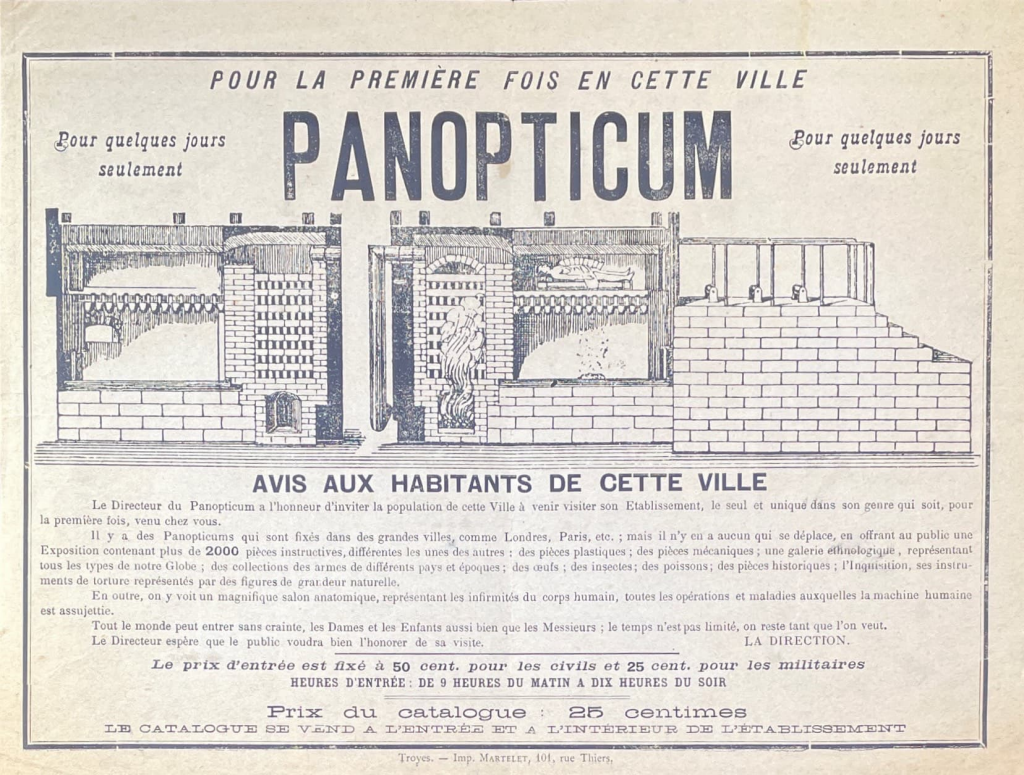

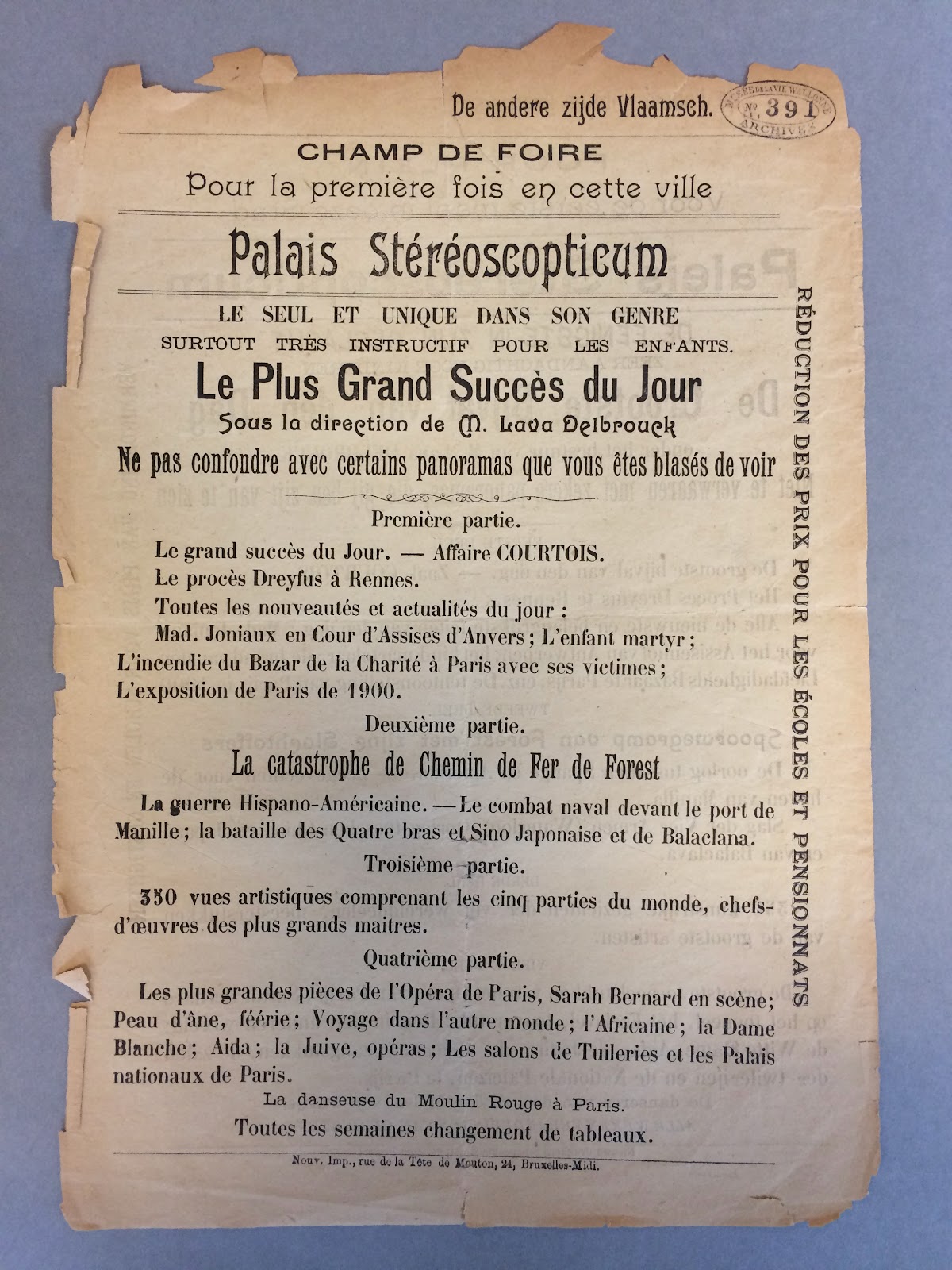

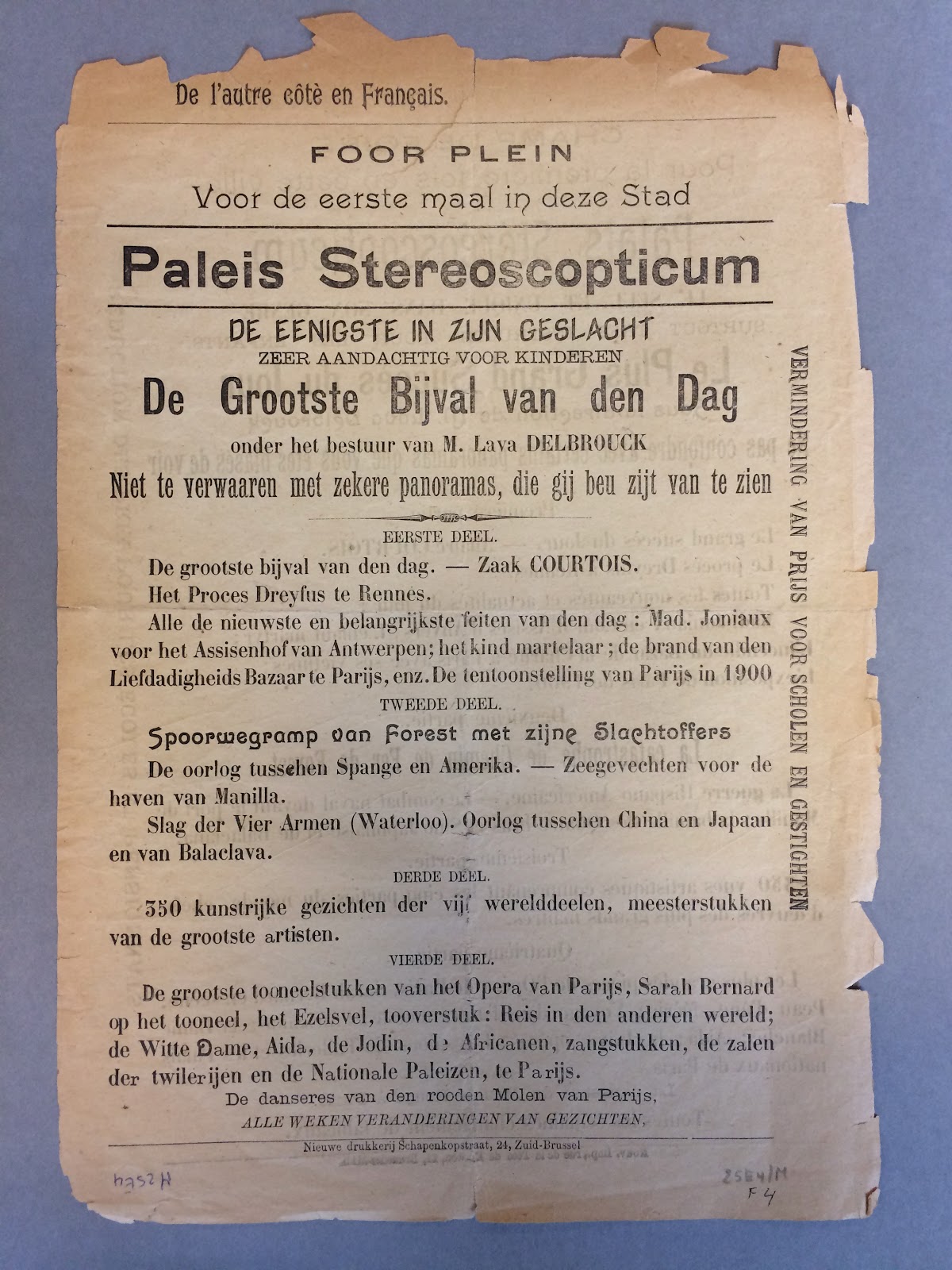

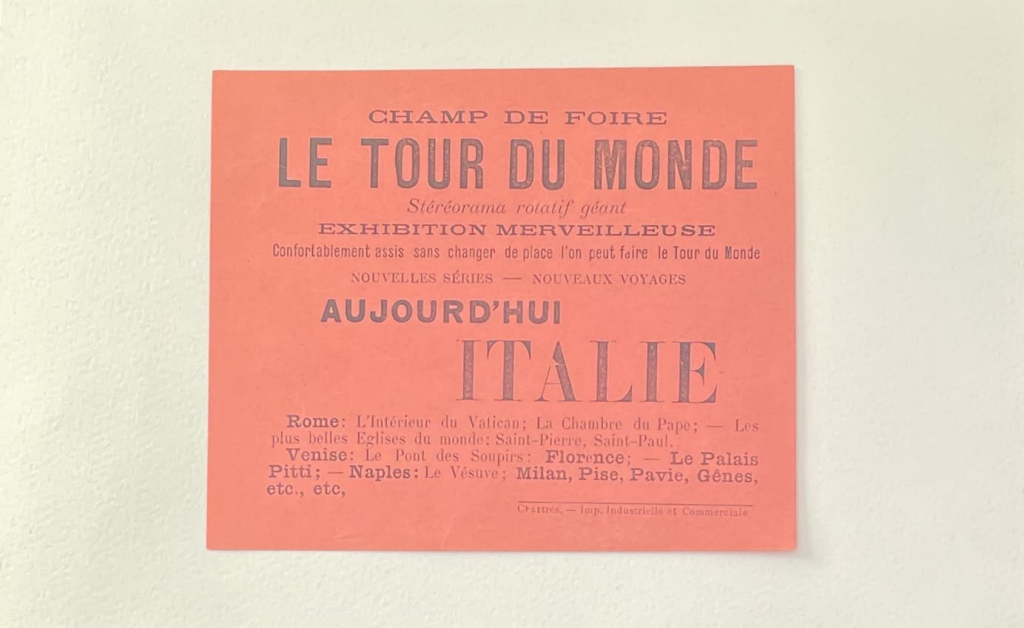

Nineteenth-century fairs facilitated a multitude of cultural encounters. Merchants offered nougat from Constantinople, while other market vendors sold Egyptian dates, rose water, and exotic spices. This unique mix of goods gave visitors the sense of experiencing a 'miniature world'. But the fair offered more than just culinary surprises — it was also a feast for the eyes. Since the Middle Ages, travelling showpeople had drawn large crowds with their visual attractions. Ballad singers illustrated their songs with large painted canvases, and in peep shows or so-called 'rarekieken', visitors could peer through a lens into a box to see a three-dimensional world unfold. There were also magic lantern spectacles that, long before the advent of film, projected colourful images onto a white screen.

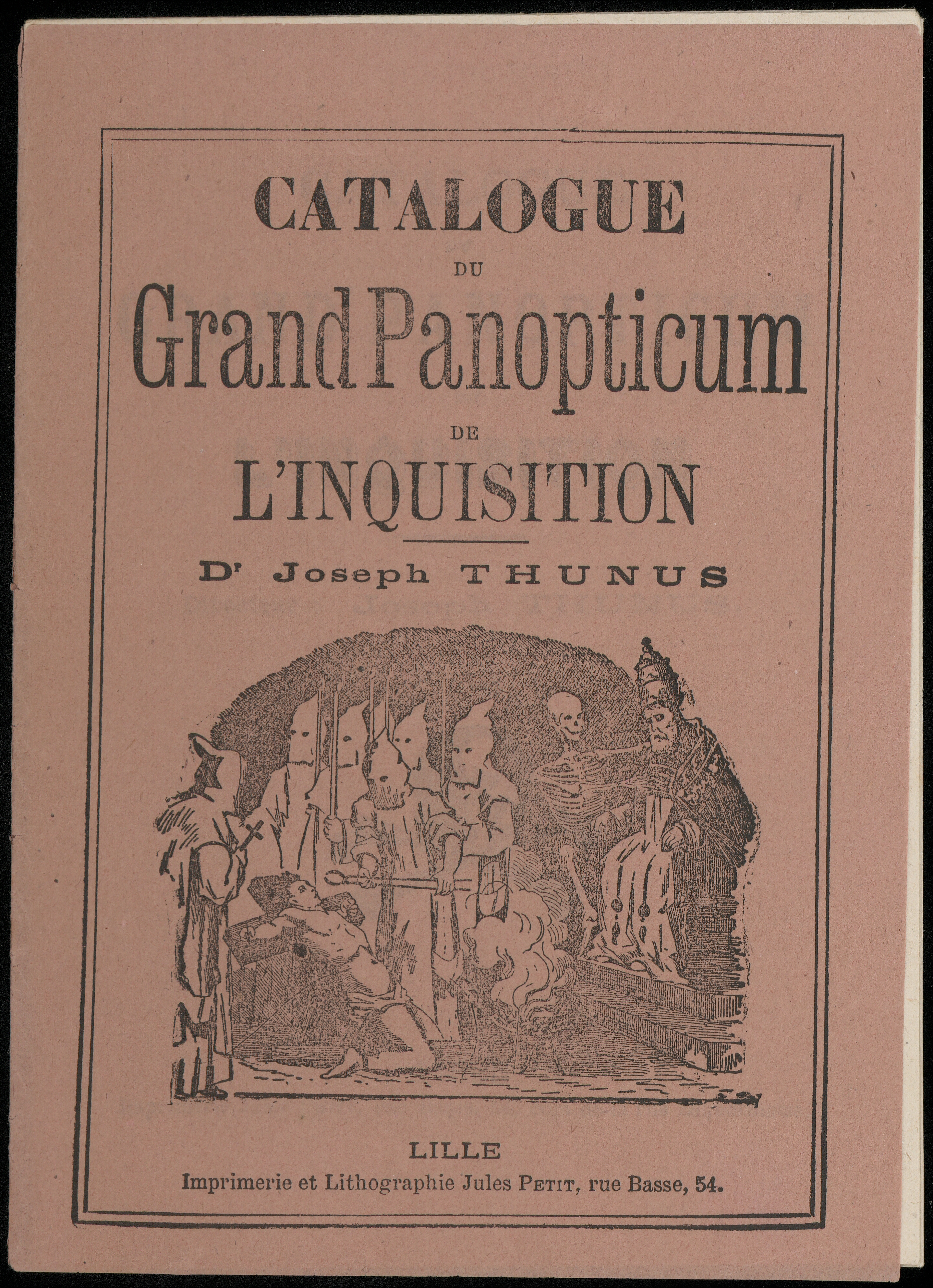

All these enchanting performances, often combined with music and live acts, reached their zenith in the nineteenth century. New media forms such as panoramas, cosmoramas, and panopticons captivated broad audiences, offering the masses a glimpse into the world and its history.

A particularly notable example of such fairground entertainment can be found in the travelling puppet theatre of the Van Weymersch family. Between 1820 and 1870, father and son Van Weymersch toured villages in East Flanders and Antwerp, where their marionette performances enchanted audiences during festivals and fairs. The true highlight came at the end of the show: a visual spectacle they proudly called 'Chinese fireworks'. For this, a transparent painting was illuminated from behind by dozens of candles. Between the candles and the painting, a perforated wheel rotated, creating flickering light effects that mimicked fireworks and brought figures of well-known personalities to life. The audience could marvel at famous religious and historical figures such as Saint Cecilia and Napoleon III. Meanwhile, the spectators were provided with detailed explanations of what they were seeing. This interplay of light, art, and storytelling made their performances truly unique.

Related Sources

Knocke_00605.jpg (Illustration)

Explore the database

The Halfpenny Showman by William Henry Pyne (Illustration, 1804)

Explore the database