Lantern pioneers

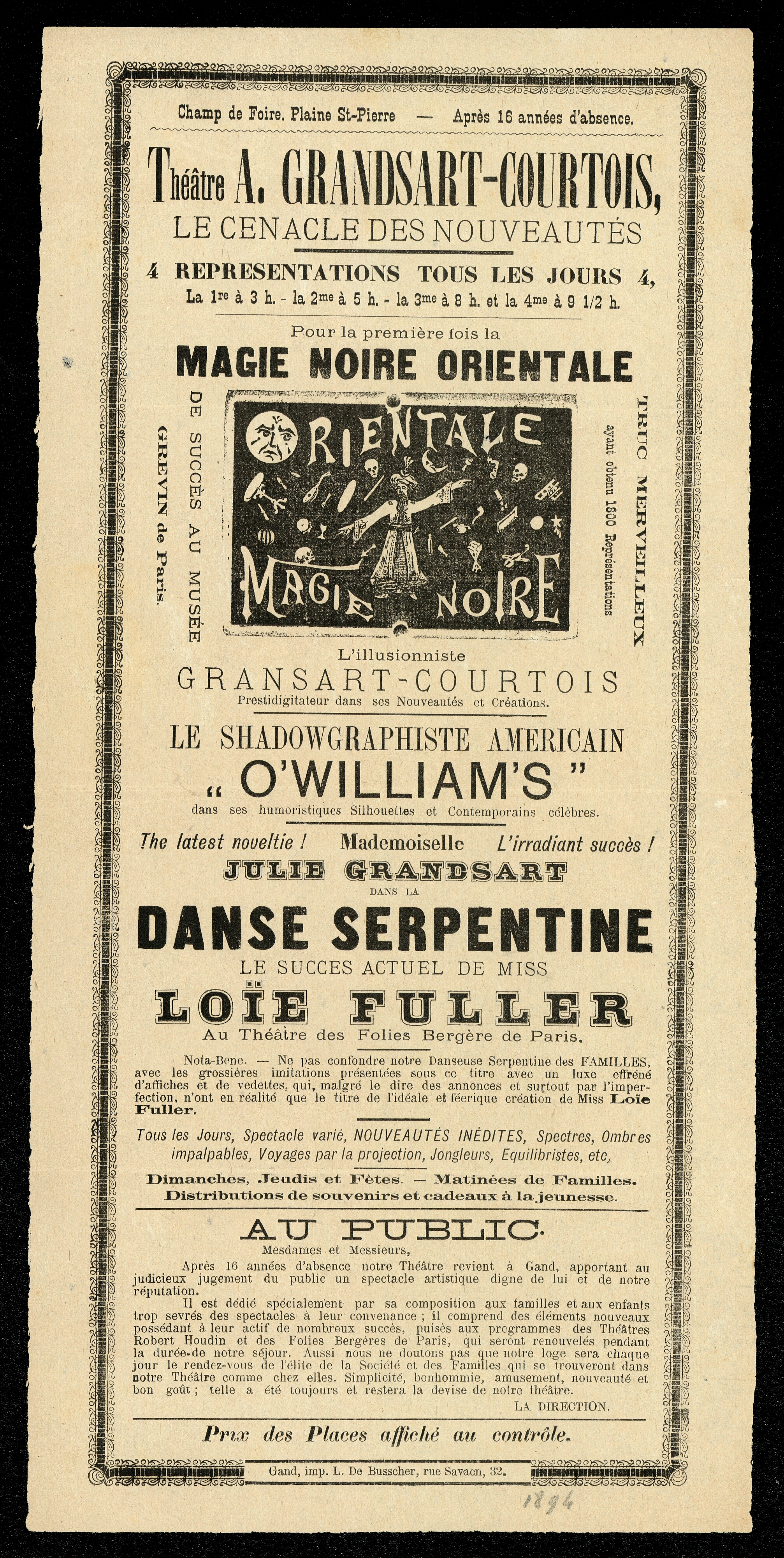

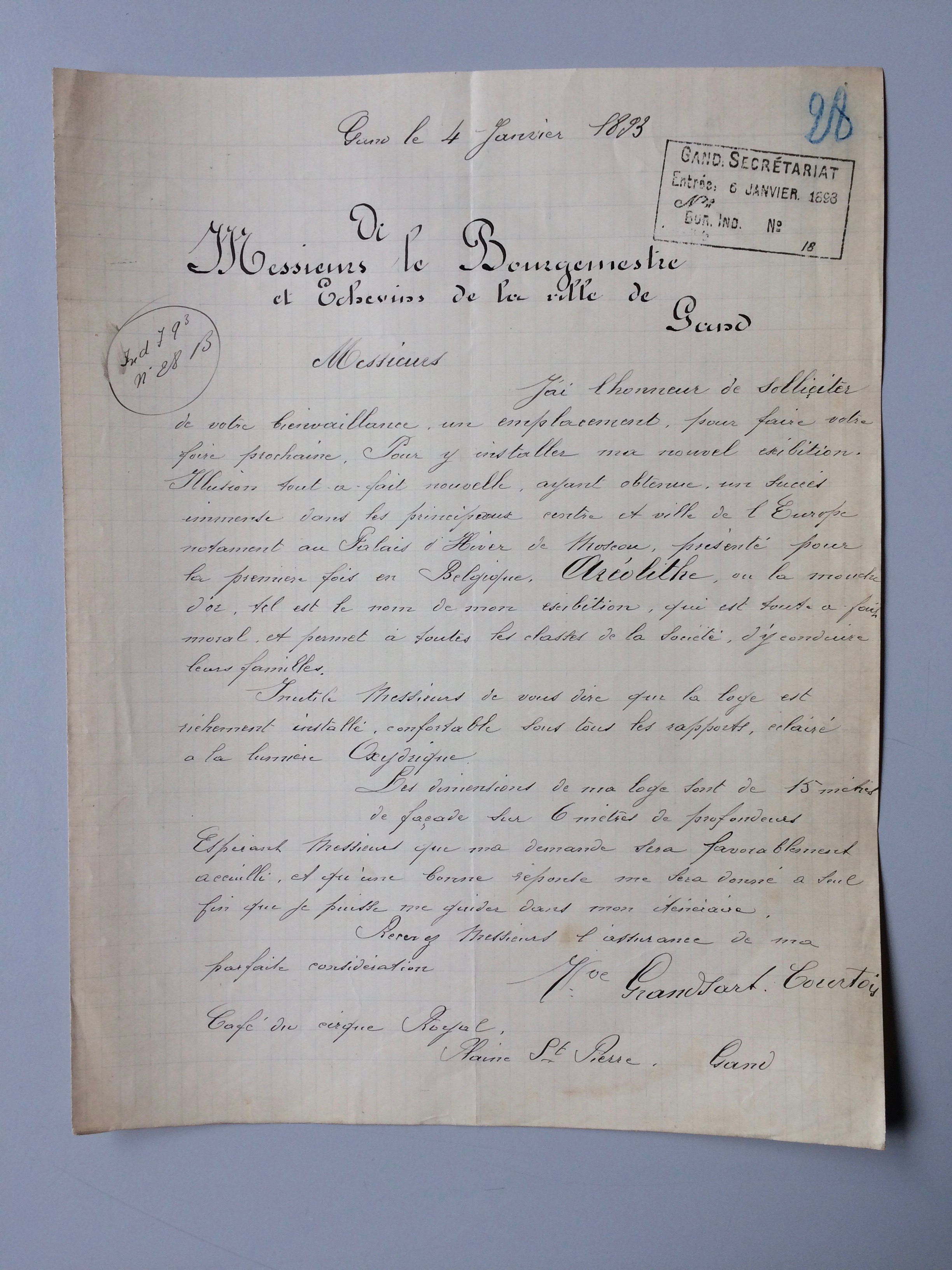

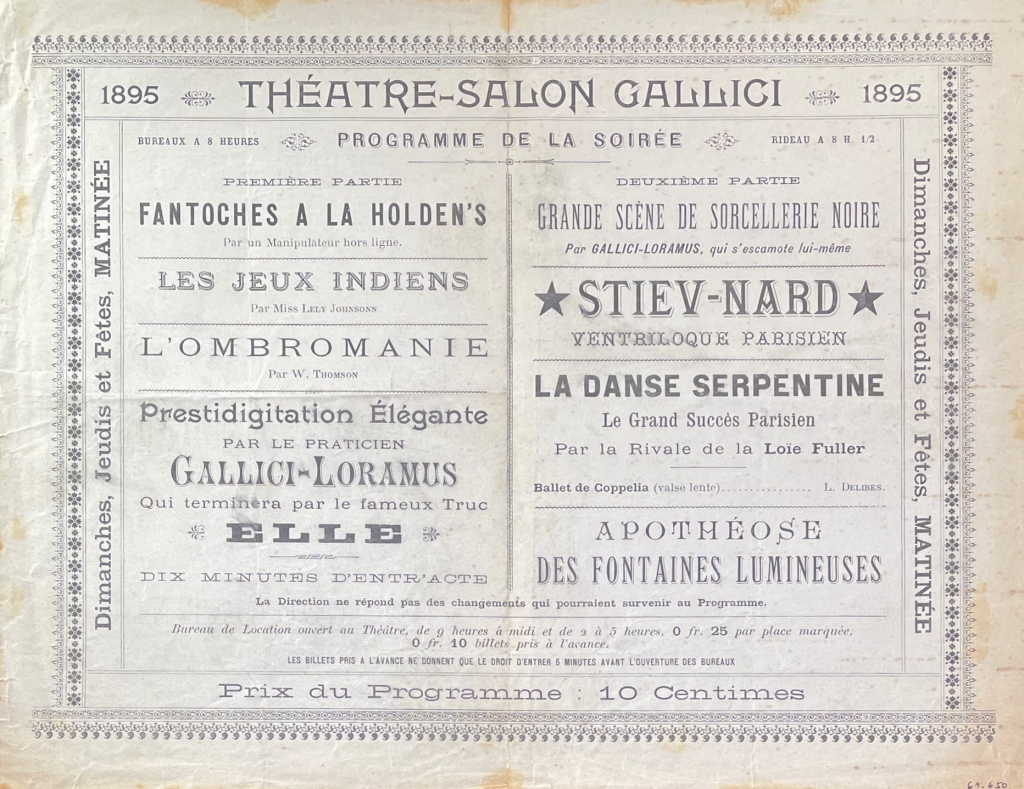

The Courtois family achieved international renown with the theatre of Louis Courtois, best known as 'Papa Courtois'. Louis, born in Waasmunster in 1785, was a visionary who acquired a magic lantern long before its breakthrough as a visual mass medium. As a son of itinerant showpeople, he inherited their nomadic lifestyle as well as their creative talent, which he combined with his fascination for technology and illusion. According to the press, his experiments with life-size puppets and optical instruments depicted various scenes of a bygone era. His shows were heralded as 'cabinets de physique et mécanique' and included spectacular optical demonstrations with the lantern as a highlight.

As early as 1818, Courtois and his family toured Flemish fairs in cities such as Ghent and Bruges, where he projected 'Italian Nighttime Scenes' with his lantern. Audiences were captivated by the large, bright images that took them to far-off places often only known from stories. The programme intertwined imagination with the macabre. In 1824, Louis moved to Paris with his large household of nine children and his compatriot Jean-Baptiste Van Hoestenberghe. Meanwhile, their repertoire had expanded to include phantasmagoria. In the tradition of their fellow-countryman Robertson, stage name of Liège-born Etienne Gaspard Robert, they used the magic lantern for which it was best known: to make ghosts and spirits appear before a bewildered audience. The technique created a terrifying atmosphere that thrilled spectators.

Related Sources

Robertson's Phantasmagoria in Wonders of Optics by Fulgence Marion (Illustration, 1871)

Explore the database

Buytengewoon spectakel [...] de dry minnaers [...] : [...] tot slot de groote en vermaerde fantasmagorie 25-03-1831 Gent BE Buytengewoon spectakel [...] de dry minnaers [...] : [...] tot slot de groote en vermaerde fantasmagorie. (Leaflet / poster, 1831)

Explore the database

Portrait of Louis Courtois (Photo, 1859)

Explore the database