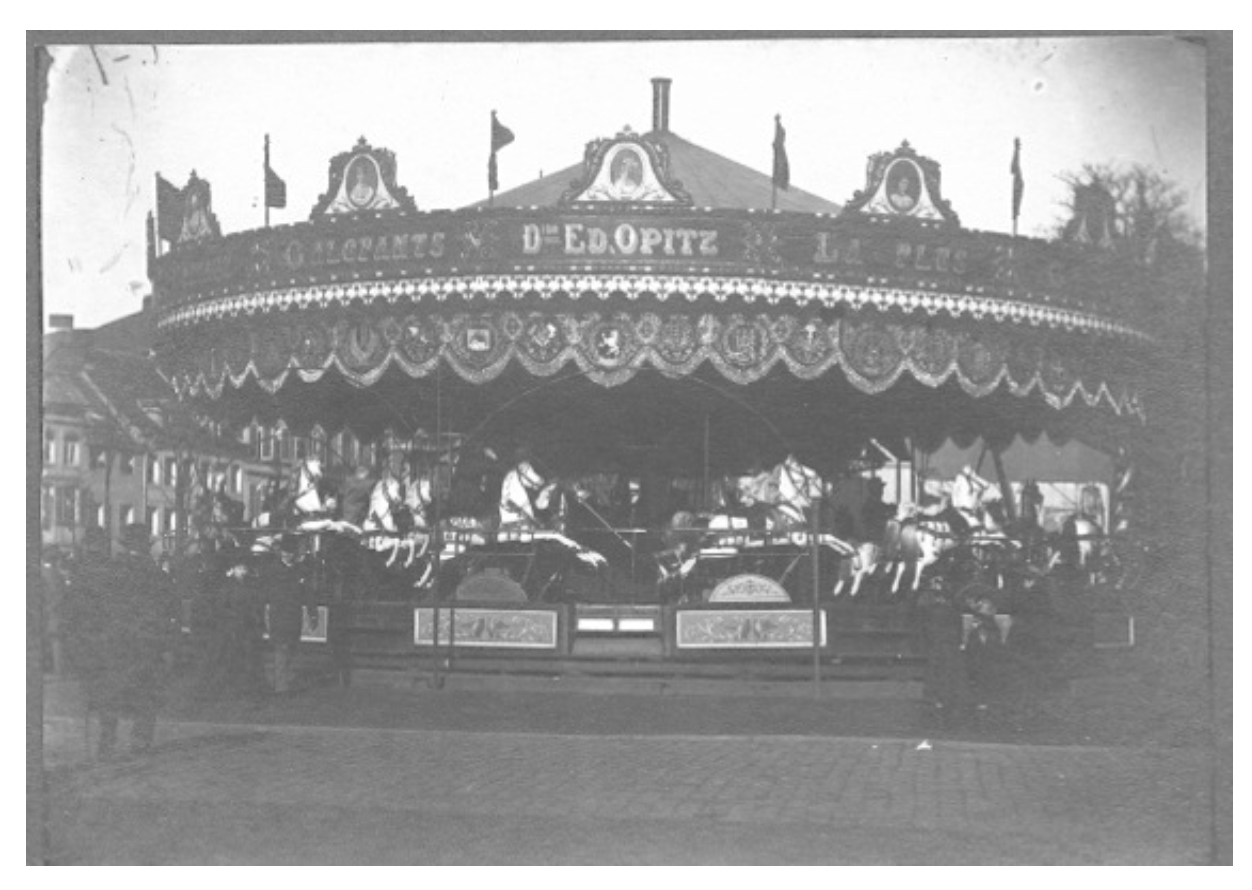

The Opitz fairground family

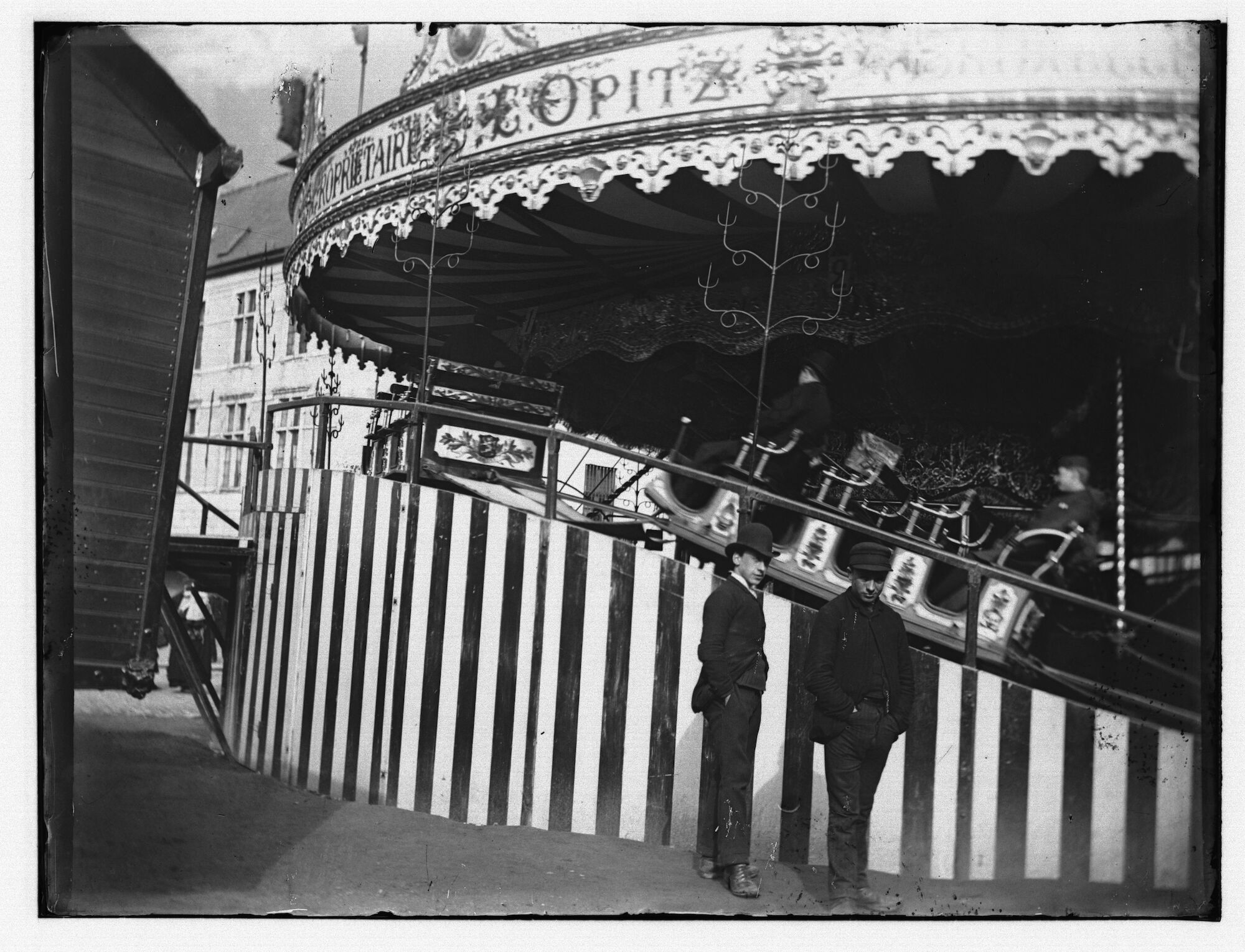

In the world of itinerant fairground families, the name Opitz certainly rings a bell. This family of German origins travelled through Western Europe in the late nineteenth century with a colourful collection of attractions. Using Belgium as their base, they mainly toured with spectacular carousels. Thanks to the newly-introduced steam power, carousels proved to be a very profitable business. Soon, the Opitz family expanded its fairground operation with associated carousel attractions, such as those of Leener-Opitz and Opitz-Van Haverbeke.

Over the years, the carousels became increasingly elaborate, culminating in the salon-carousel. This attraction not only offered a ride, but created a complete experience with tables, seating, a bar, and sometimes even a buffet. As a result, a carousel visit took on a social function as a dance and meeting hall. The role of the organ at the fair should not be underestimated: it provided (dance) music, attracted potential visitors, and masked the noise of the roaring machinery running the rides.

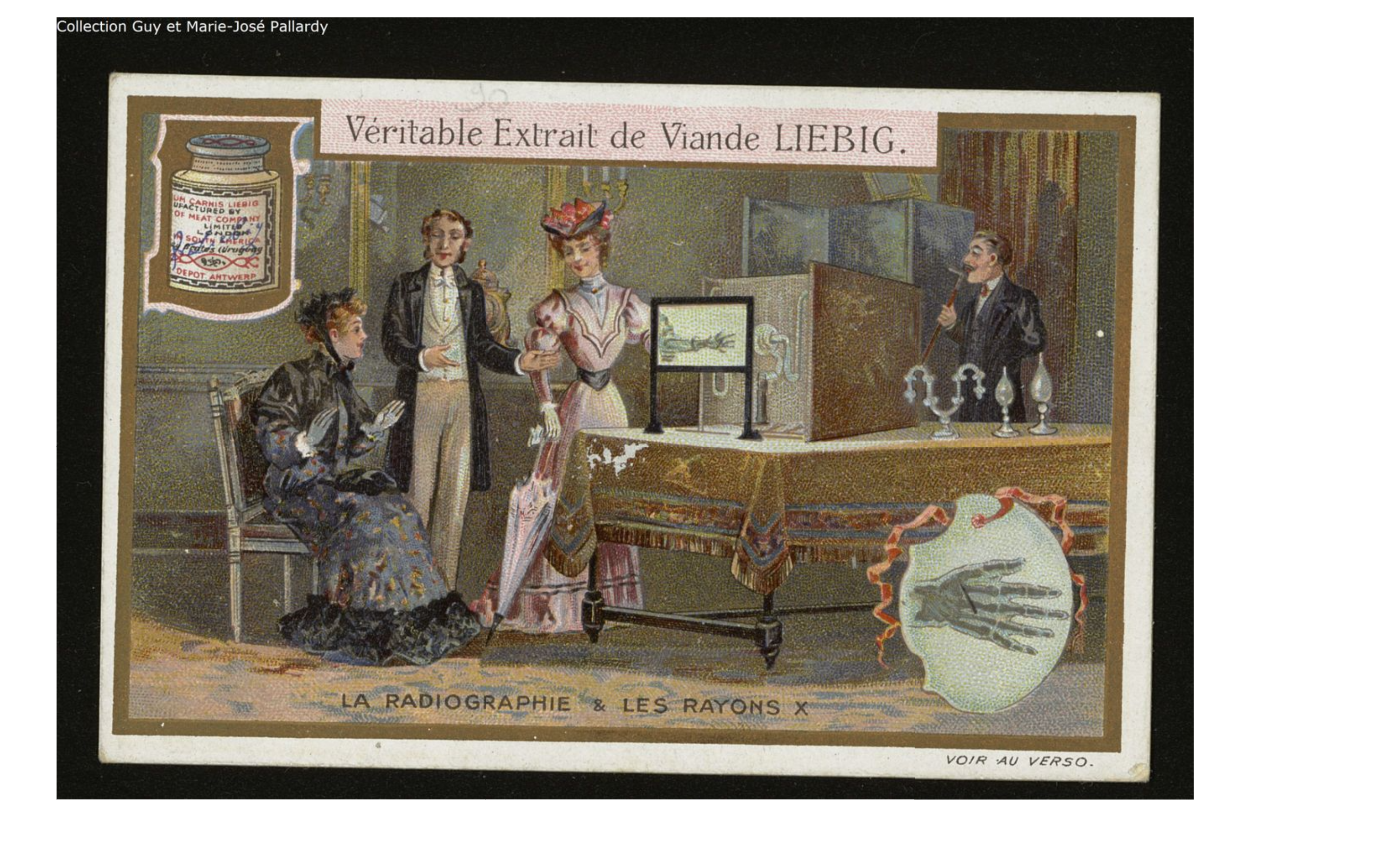

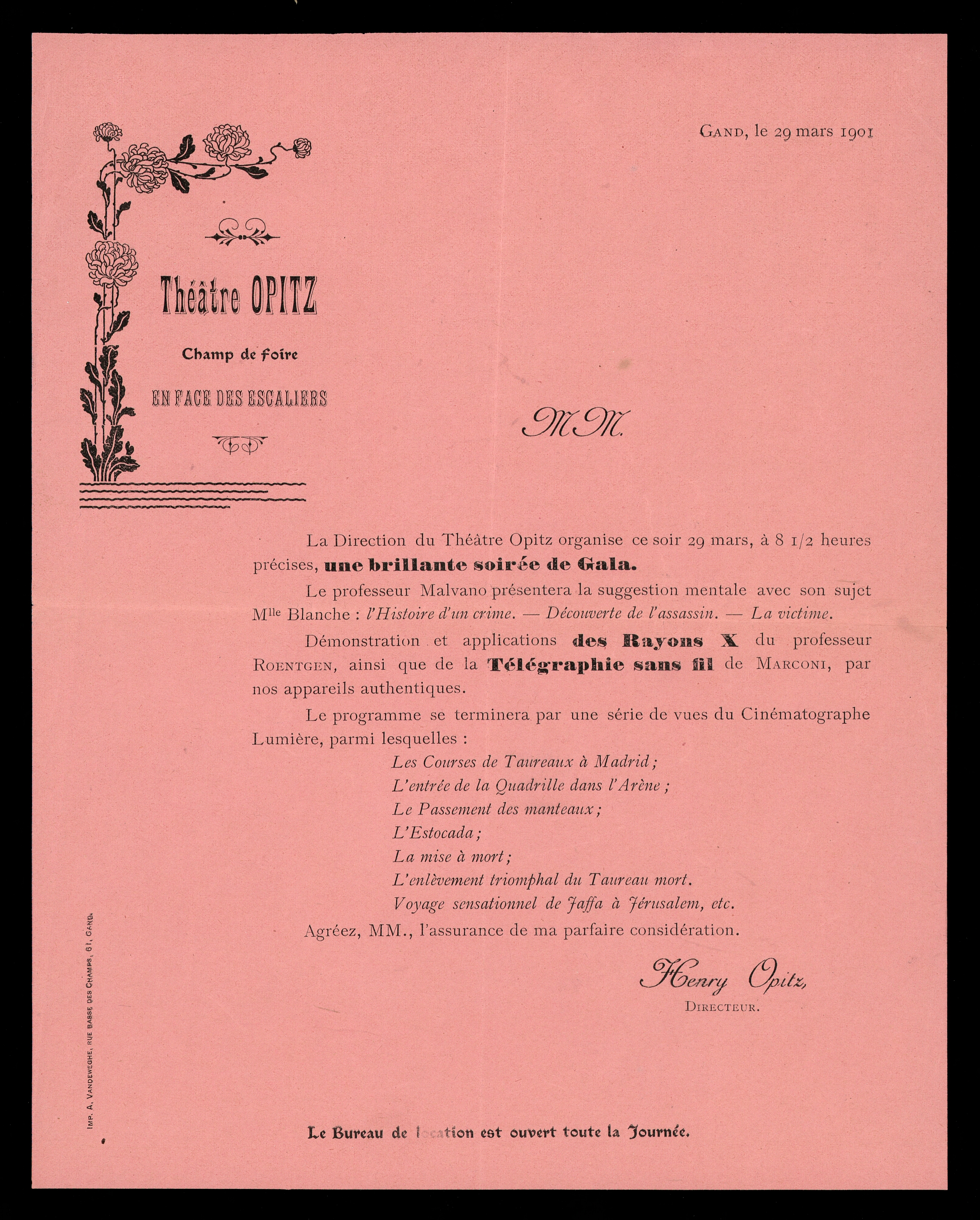

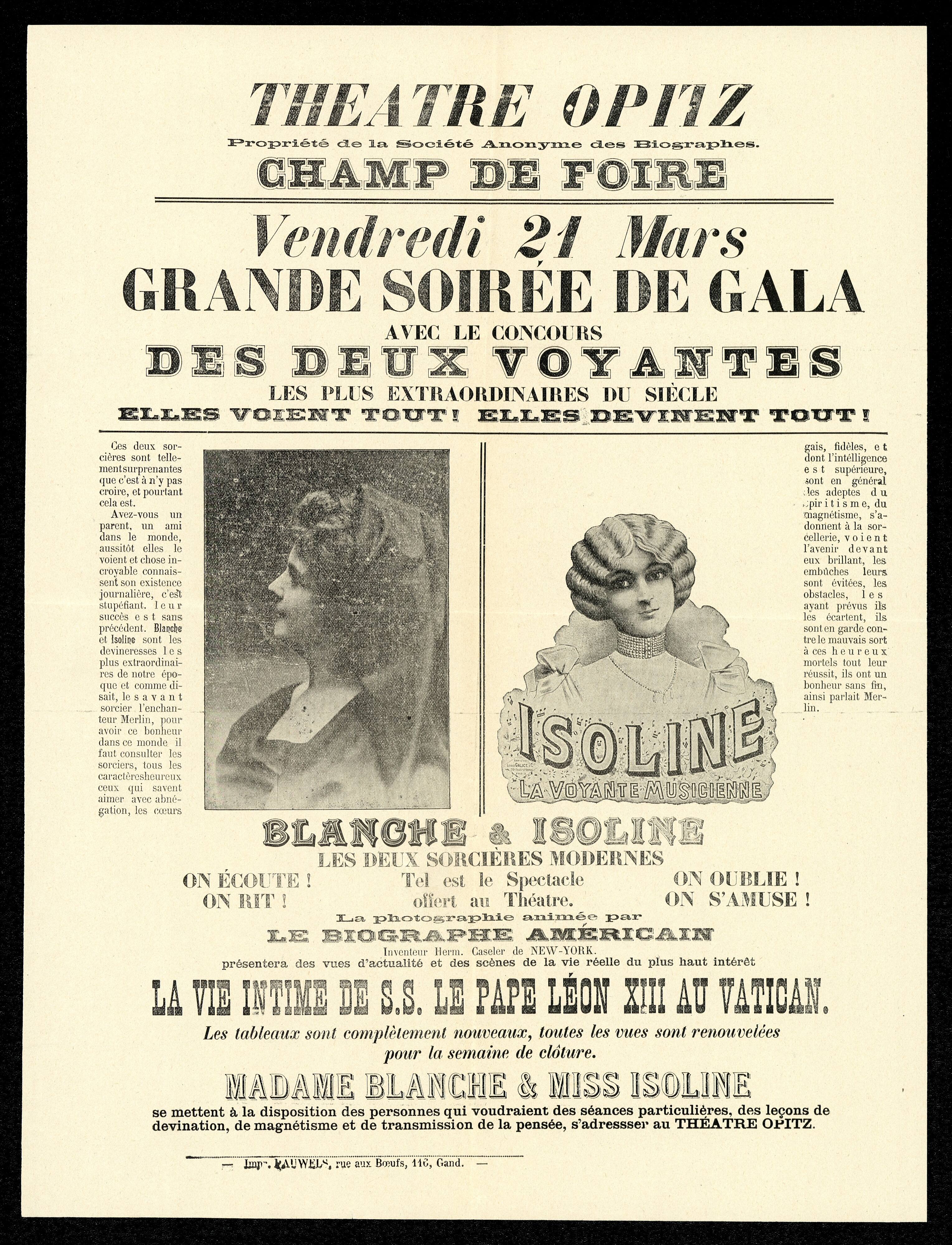

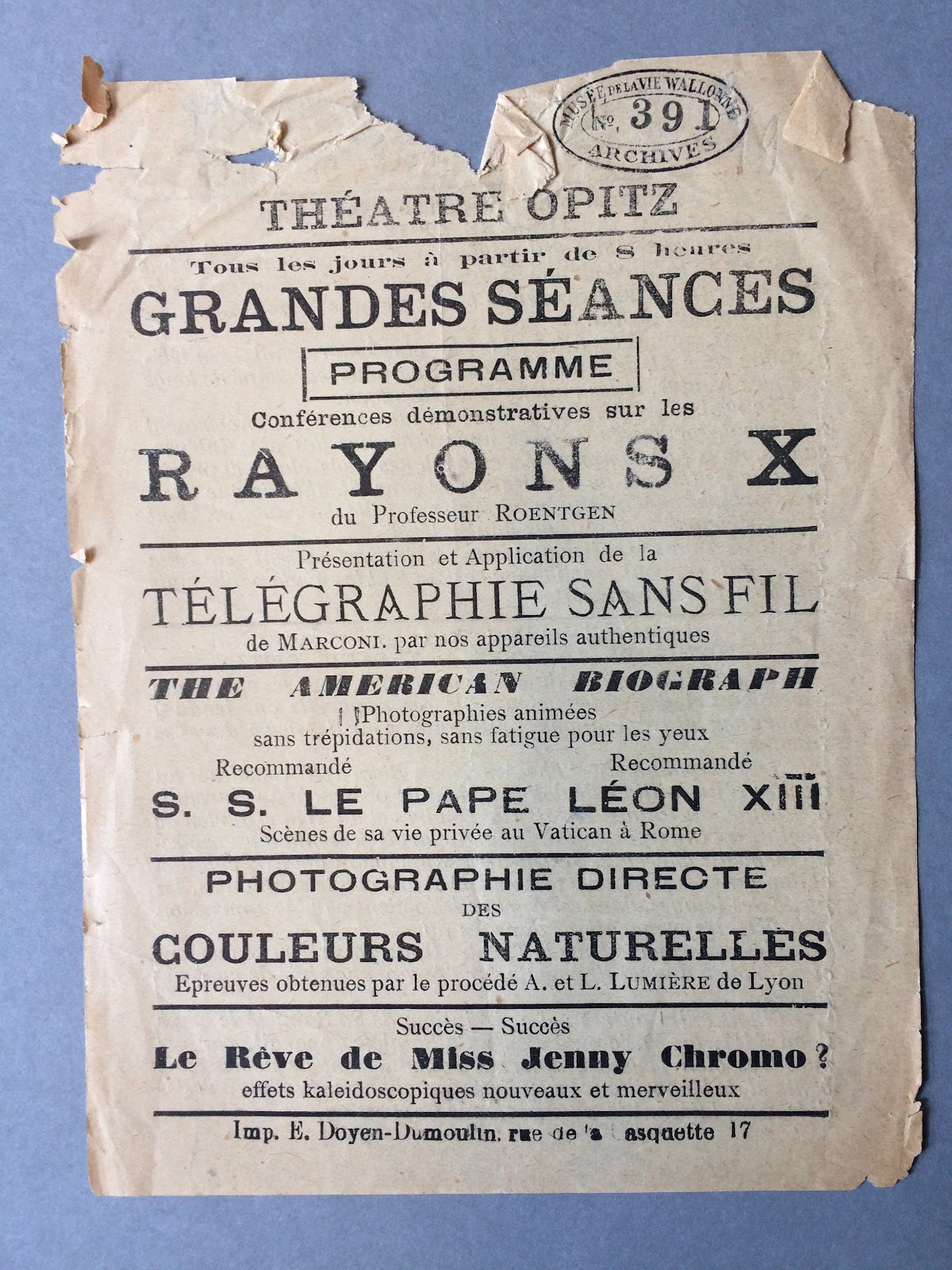

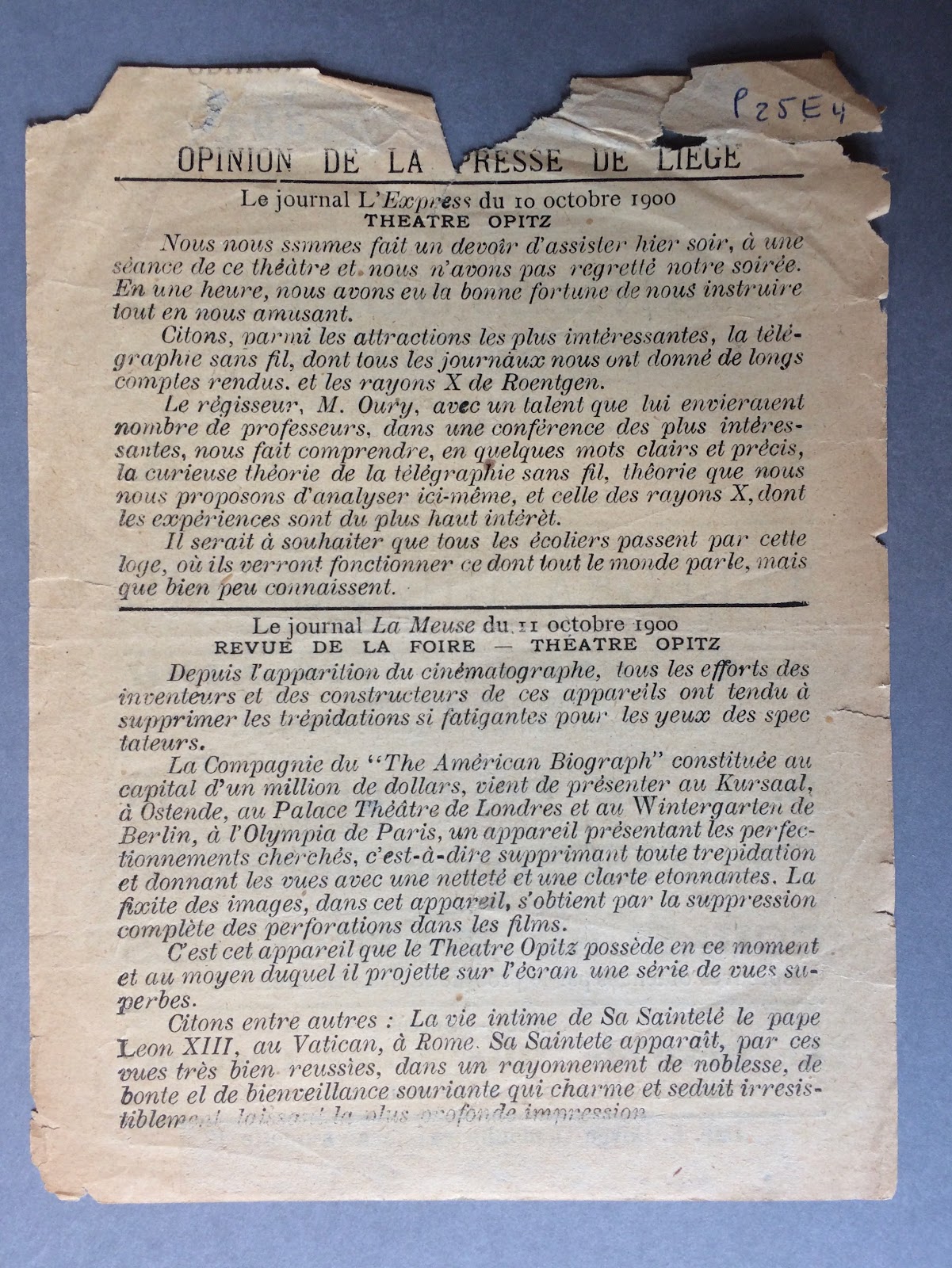

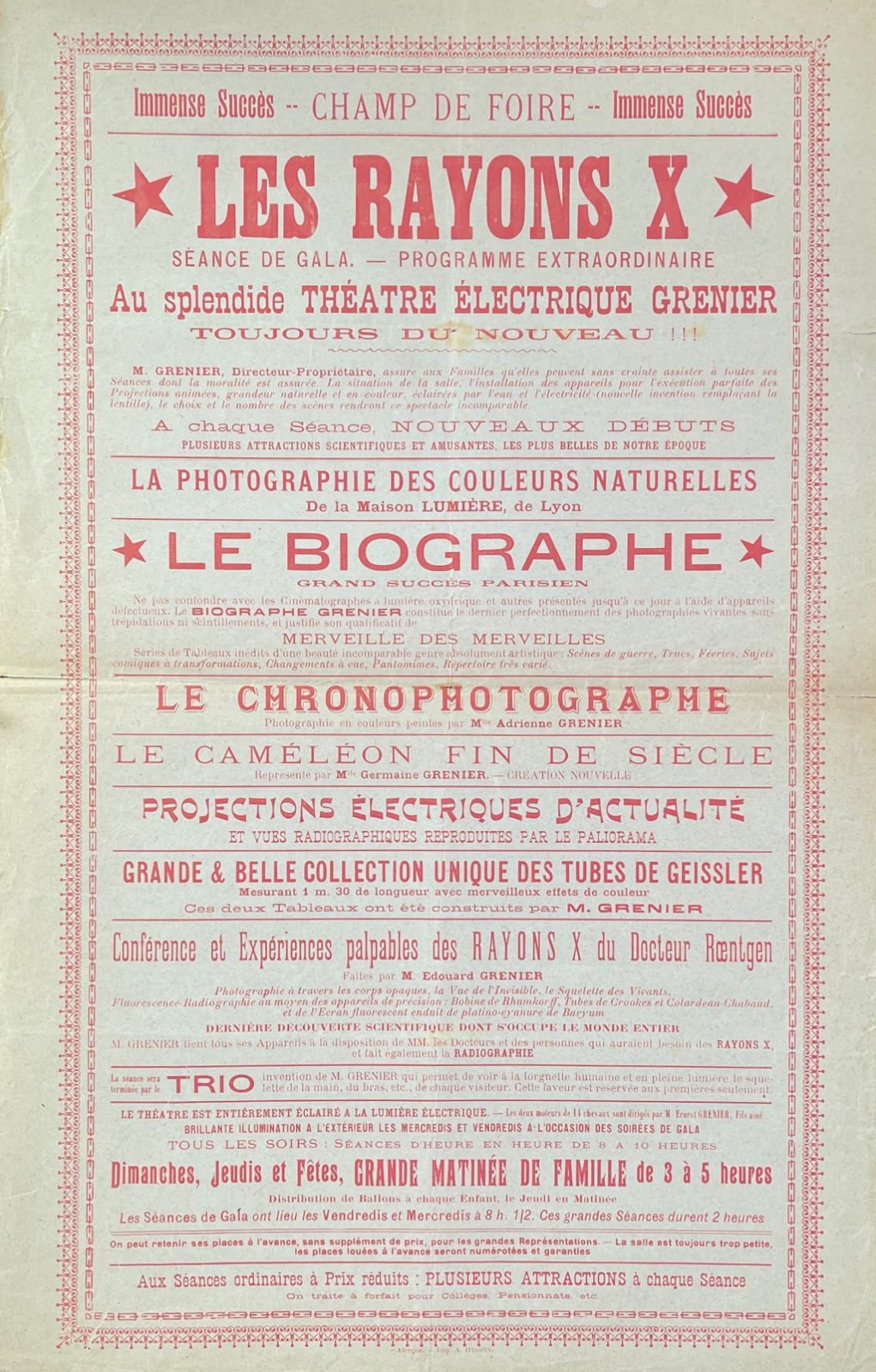

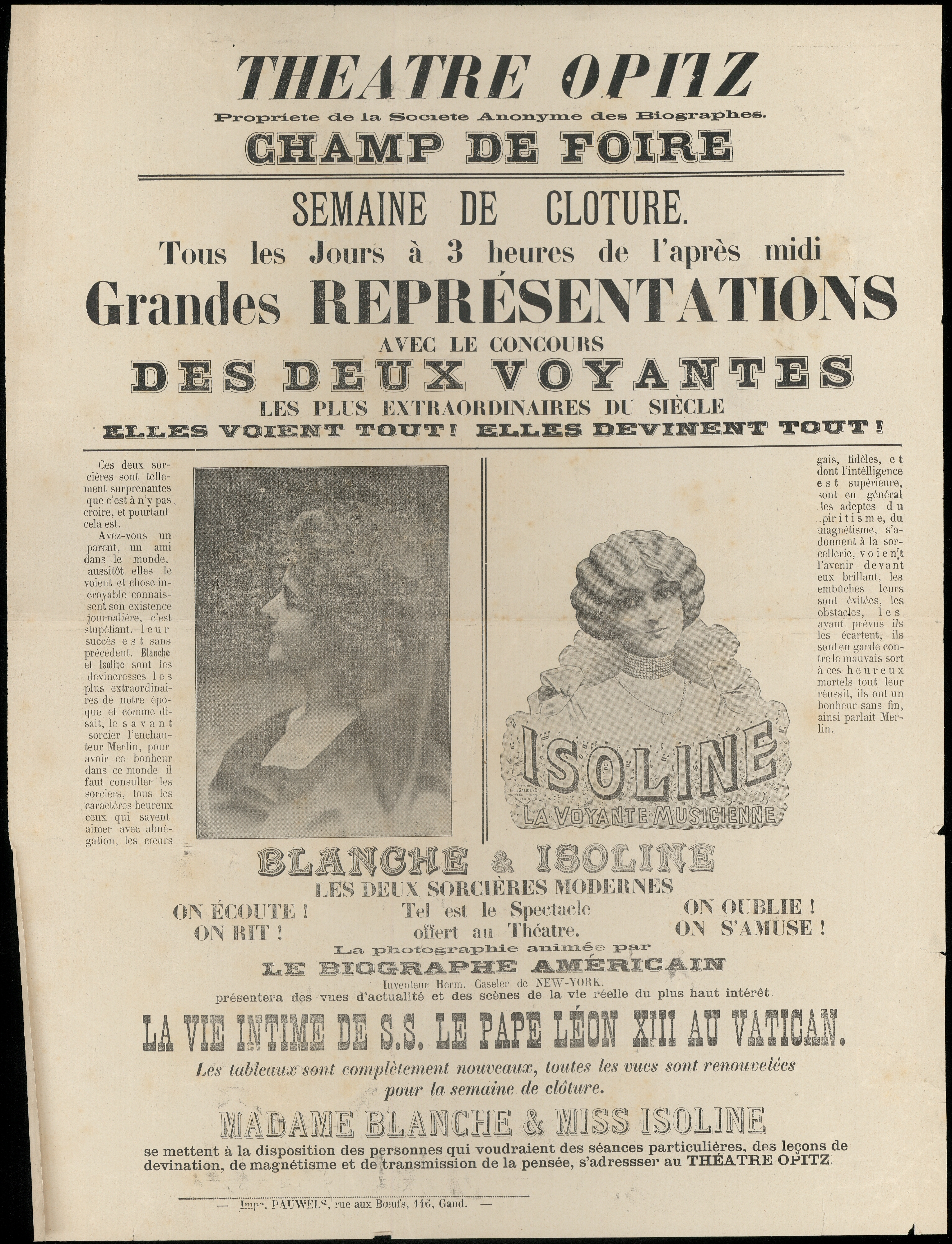

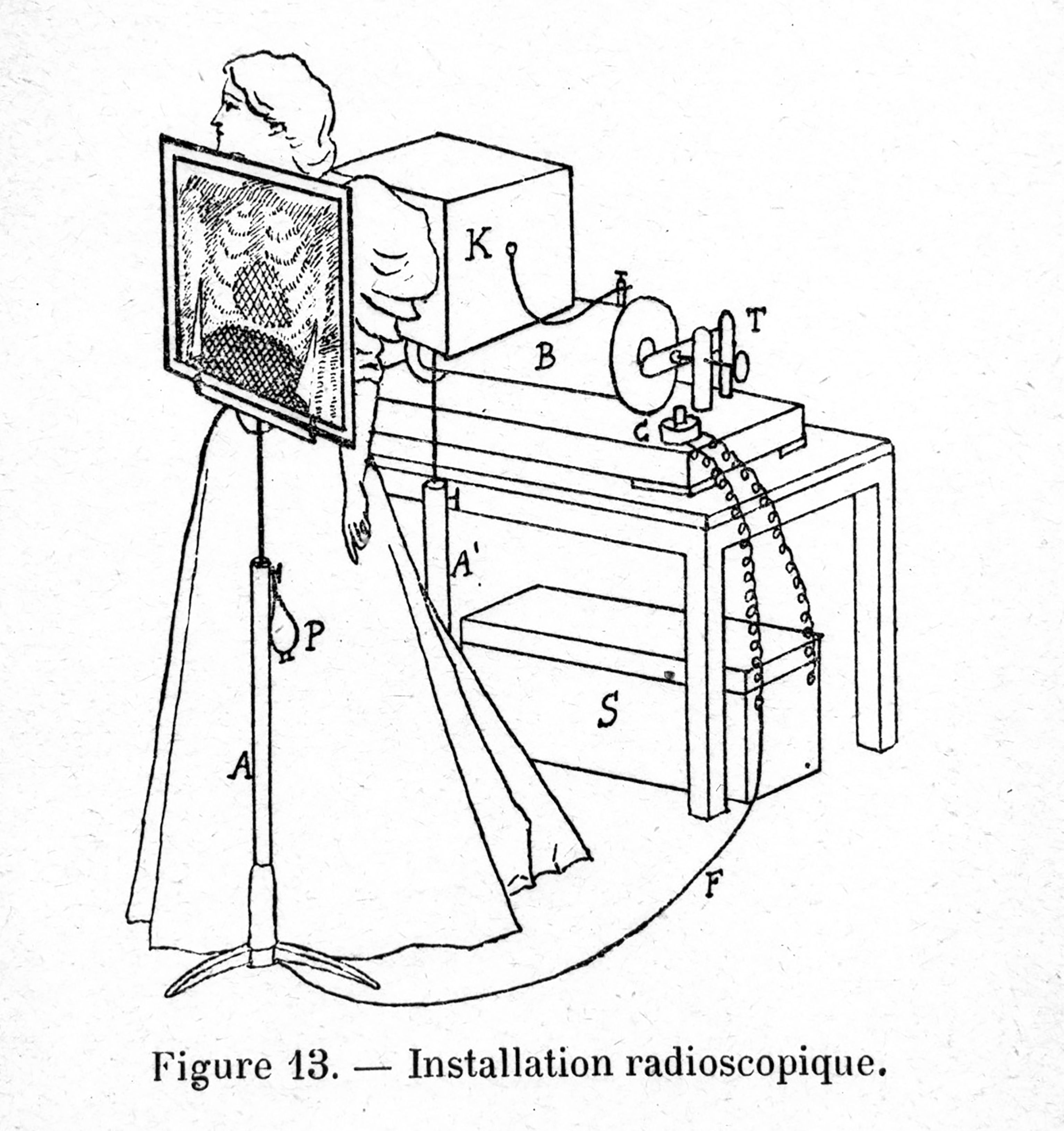

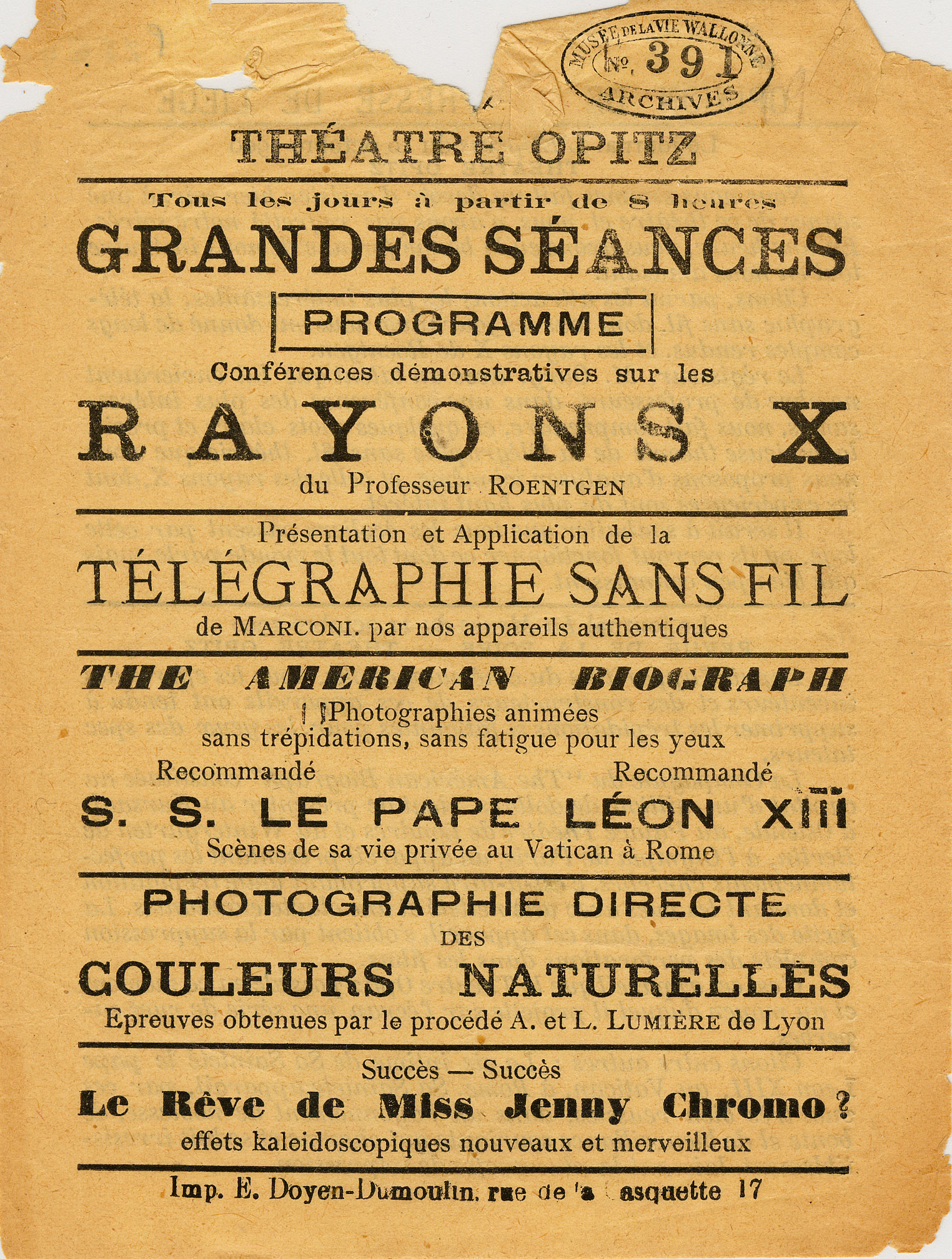

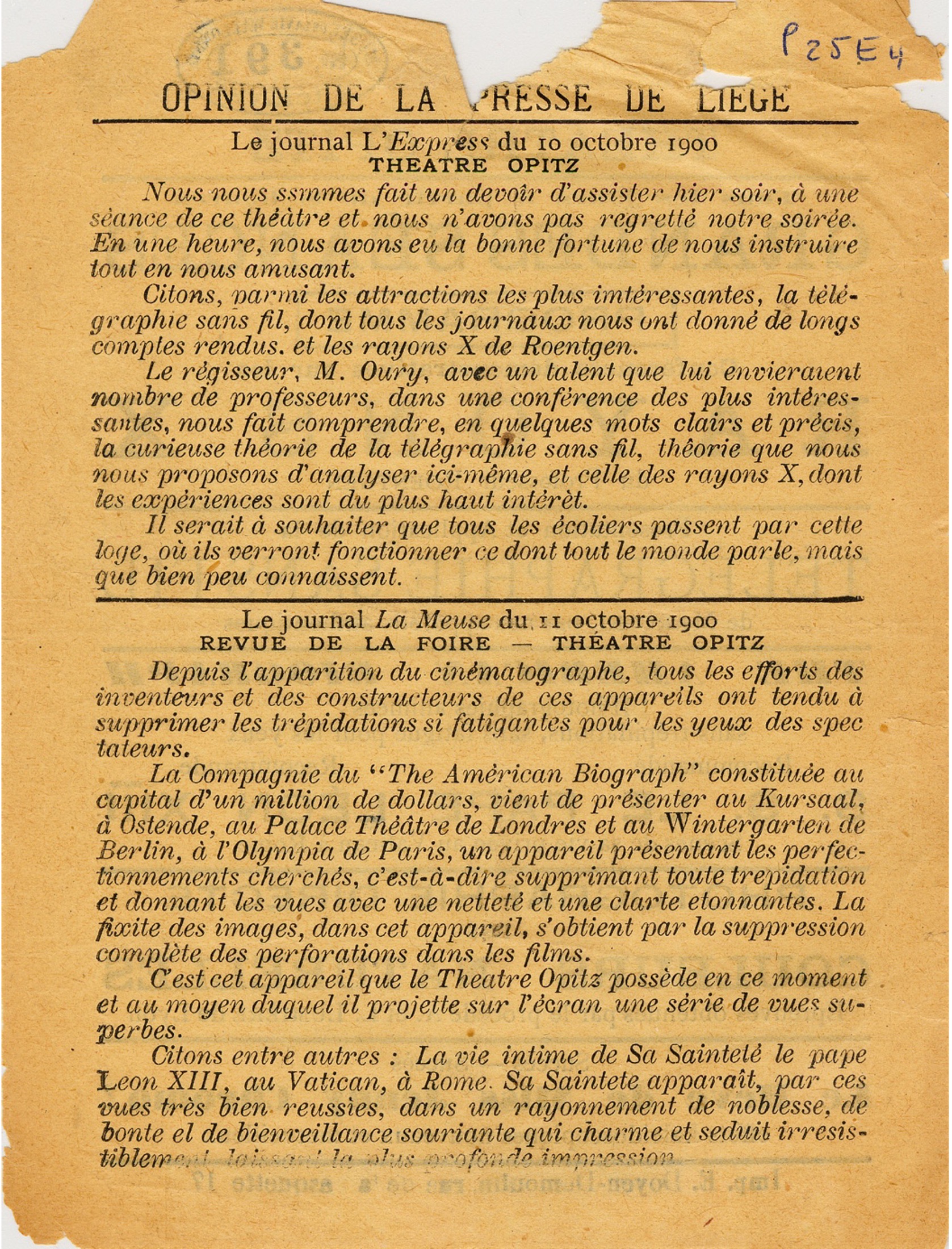

The Opitz family expanded its fairground empire to include rollercoasters and a scientific theatre under the leadership of son Henri. This went beyond the traditional forms of fairground entertainment: He introduced innovative techniques such as colour photography, wireless telegraphy, and the American biograph for playing film footage. However, the most breathtaking part of his programme was the demonstration of X-rays. The Theatre Opitz presented this 'conference on the Rayons X du Professeur Roentgen', in which Henri not only entertained his audience but also offered educational worth.

Related Sources

[unknown] Ed. Opitz, Montagnes russes H.E. Opitz (père) (Photo)

Explore the database

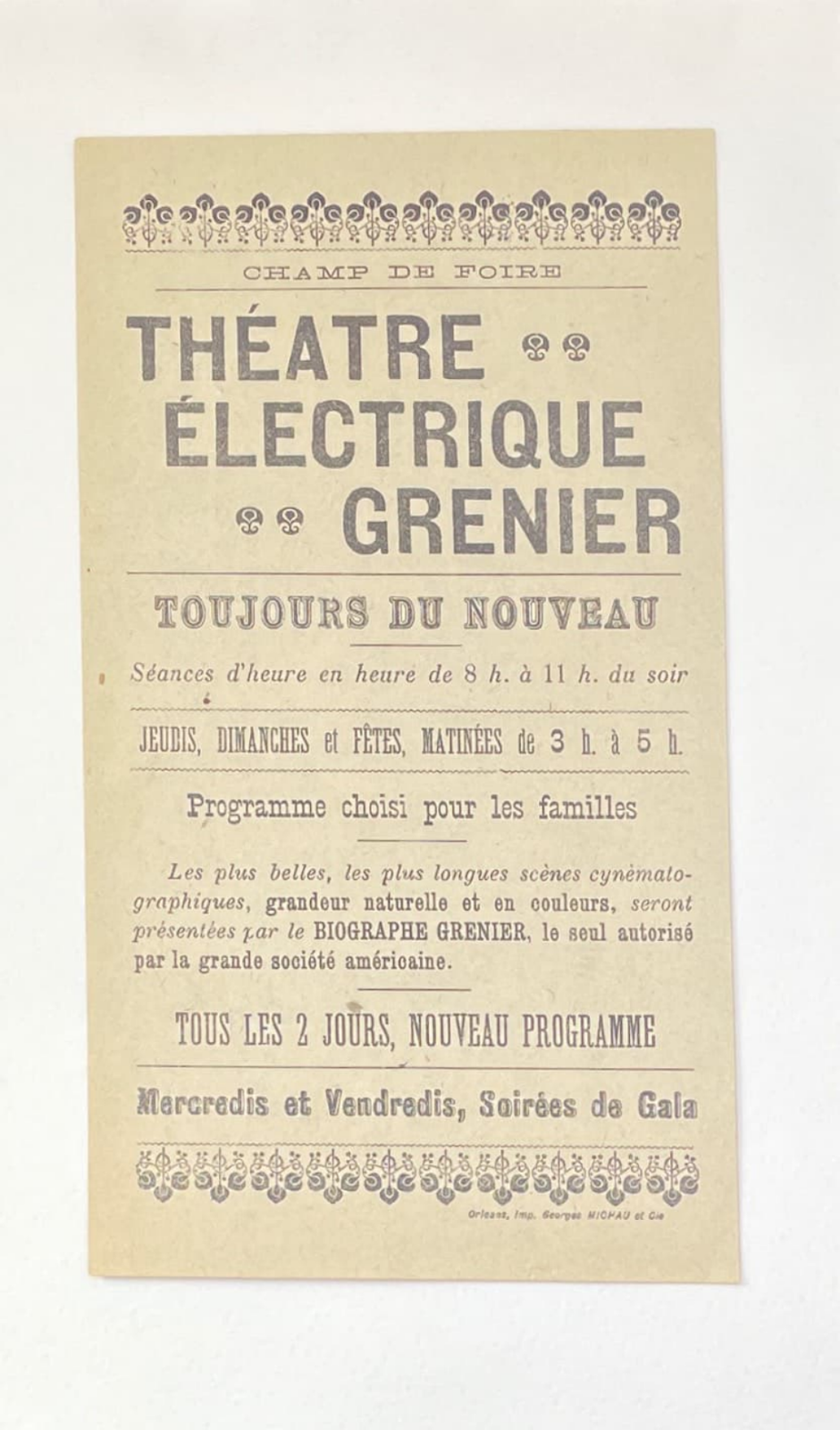

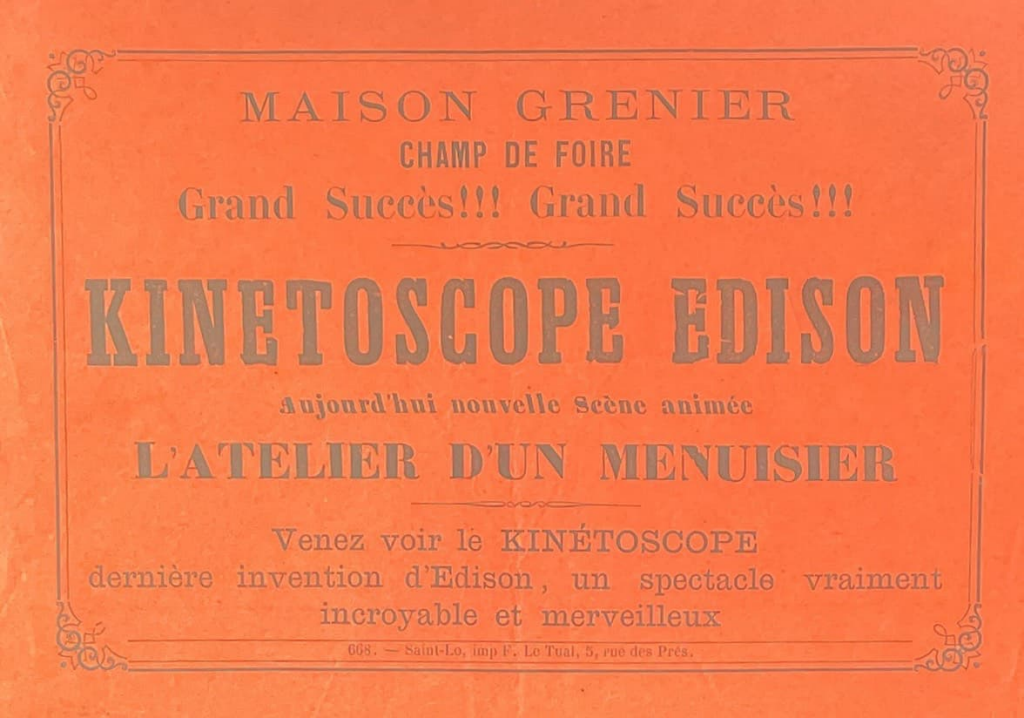

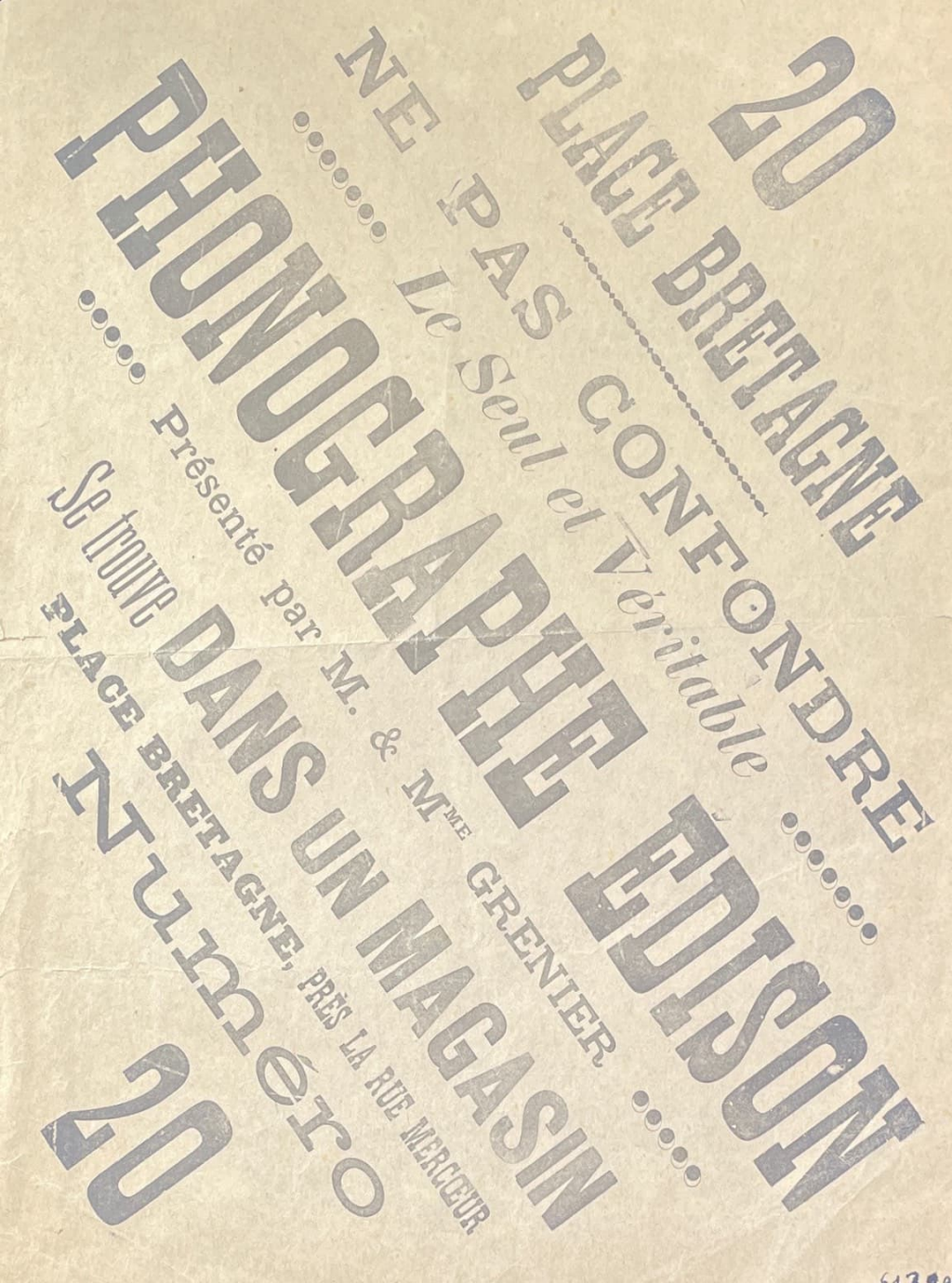

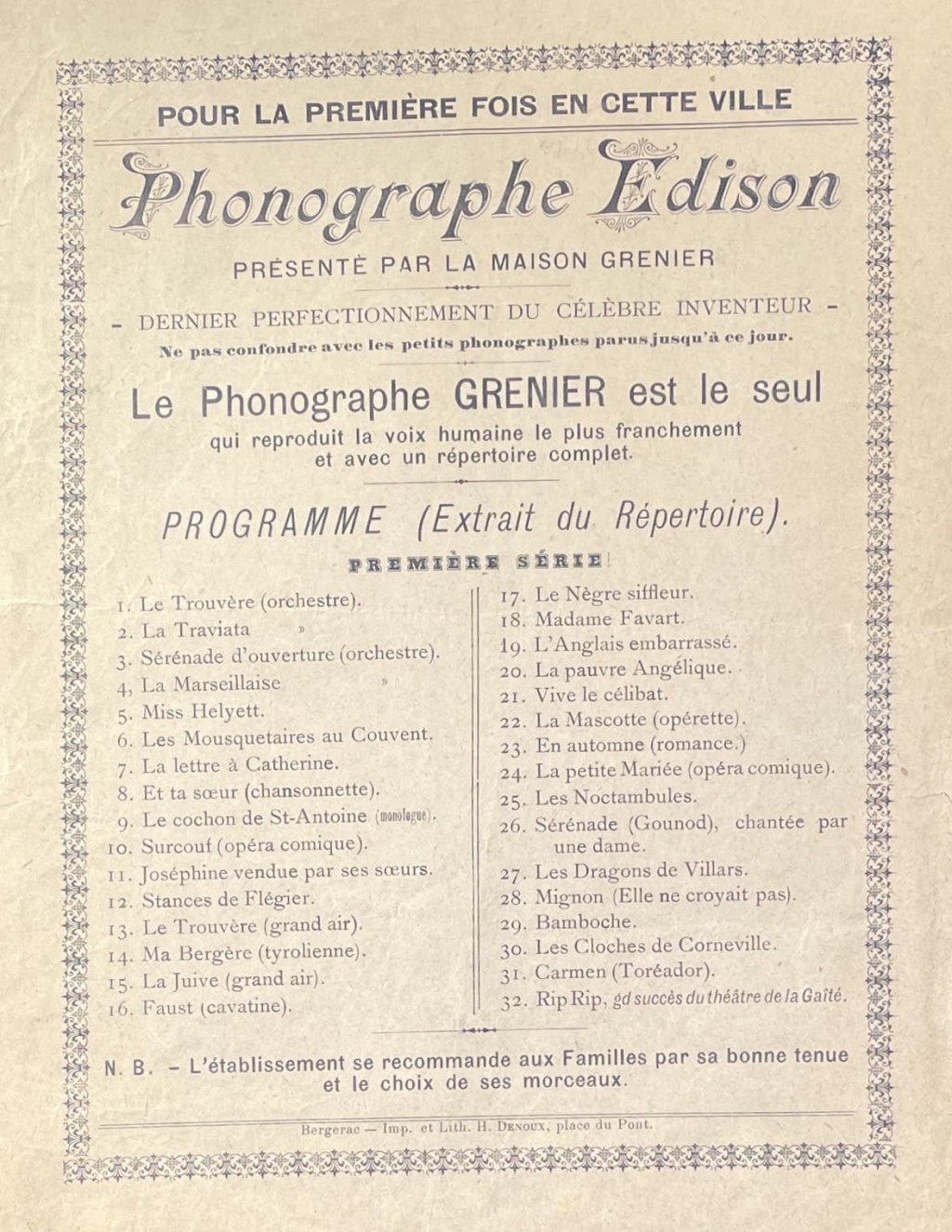

Théâtre Opitz (Leaflet / poster, 1900)

Explore the database

Théâtre Opitz (Leaflet / poster, 1900)

Explore the database

Carousel Eduard Opitz (Photo)

Explore the database

Knocke_PC_00963.jpg (Photo)

Explore the database

Knocke_PC_00963.jpg (Photo)

Explore the database