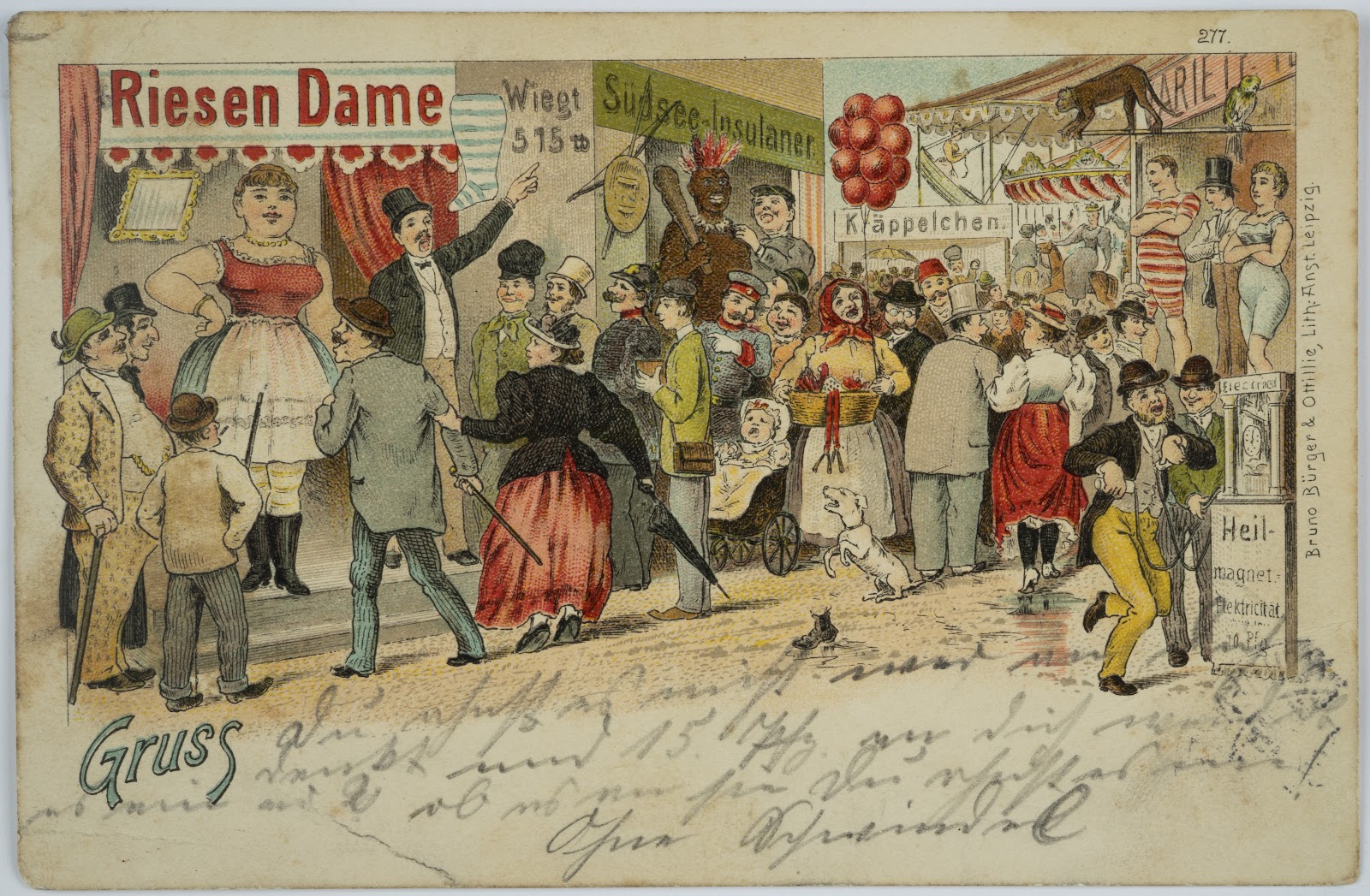

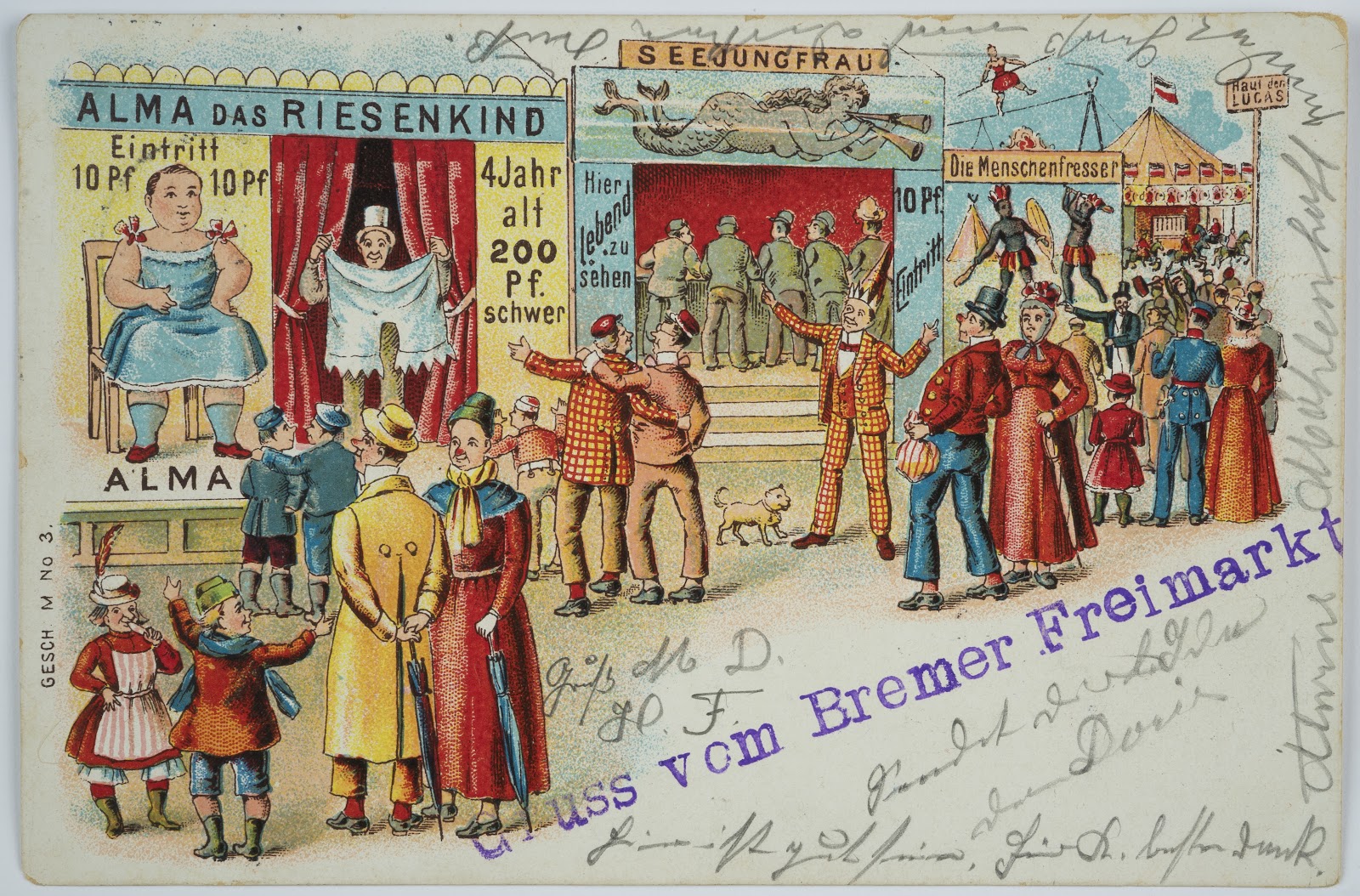

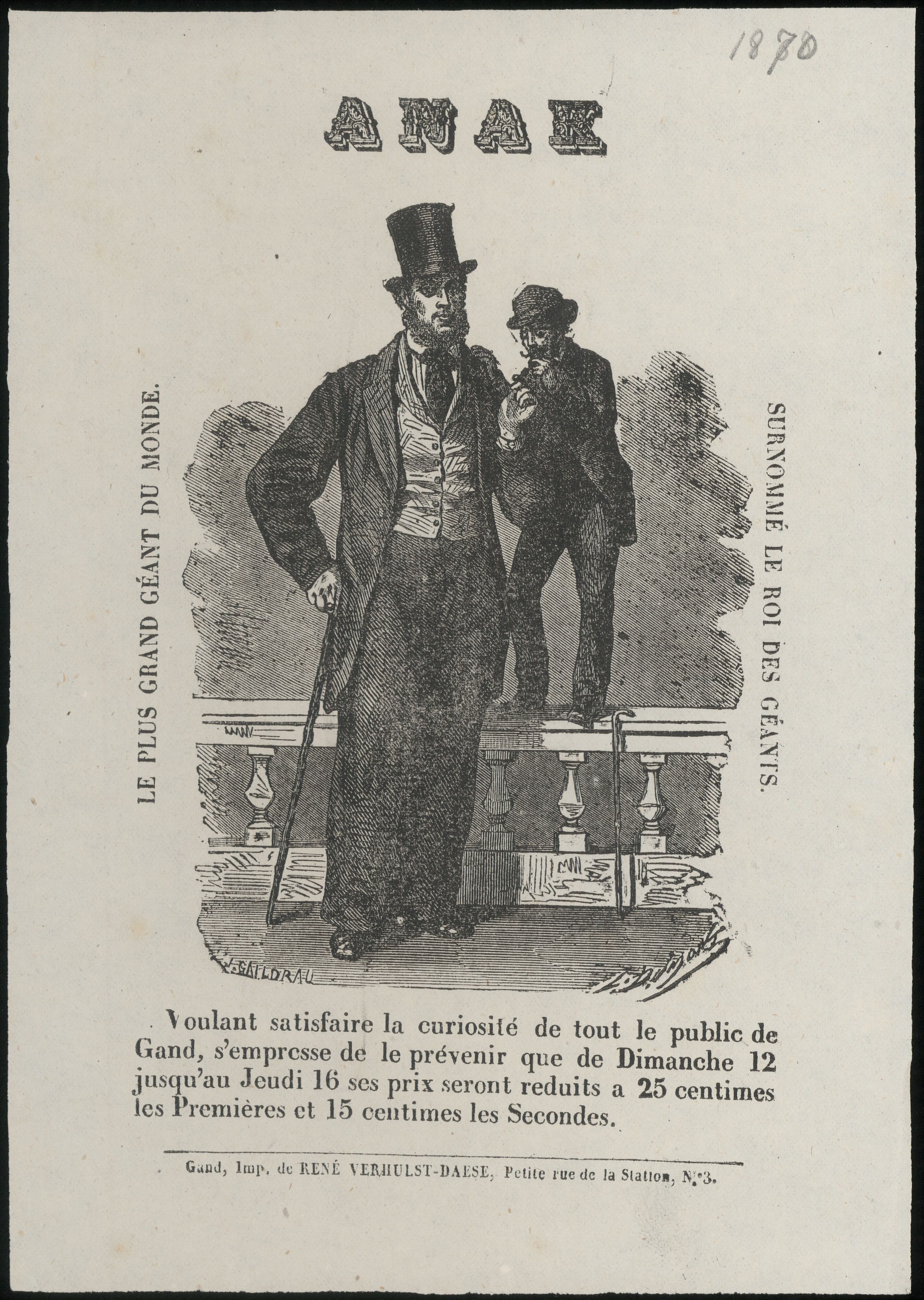

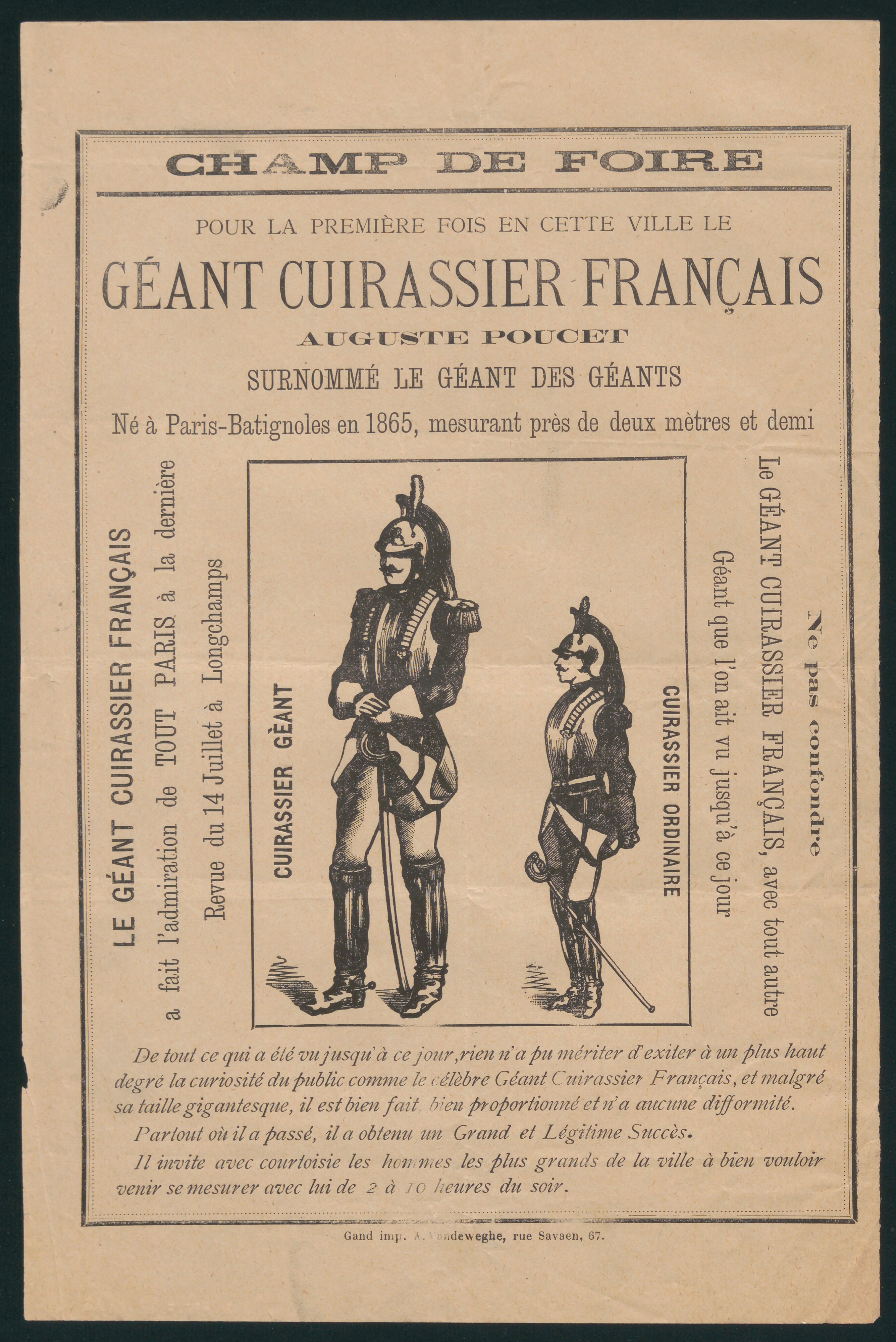

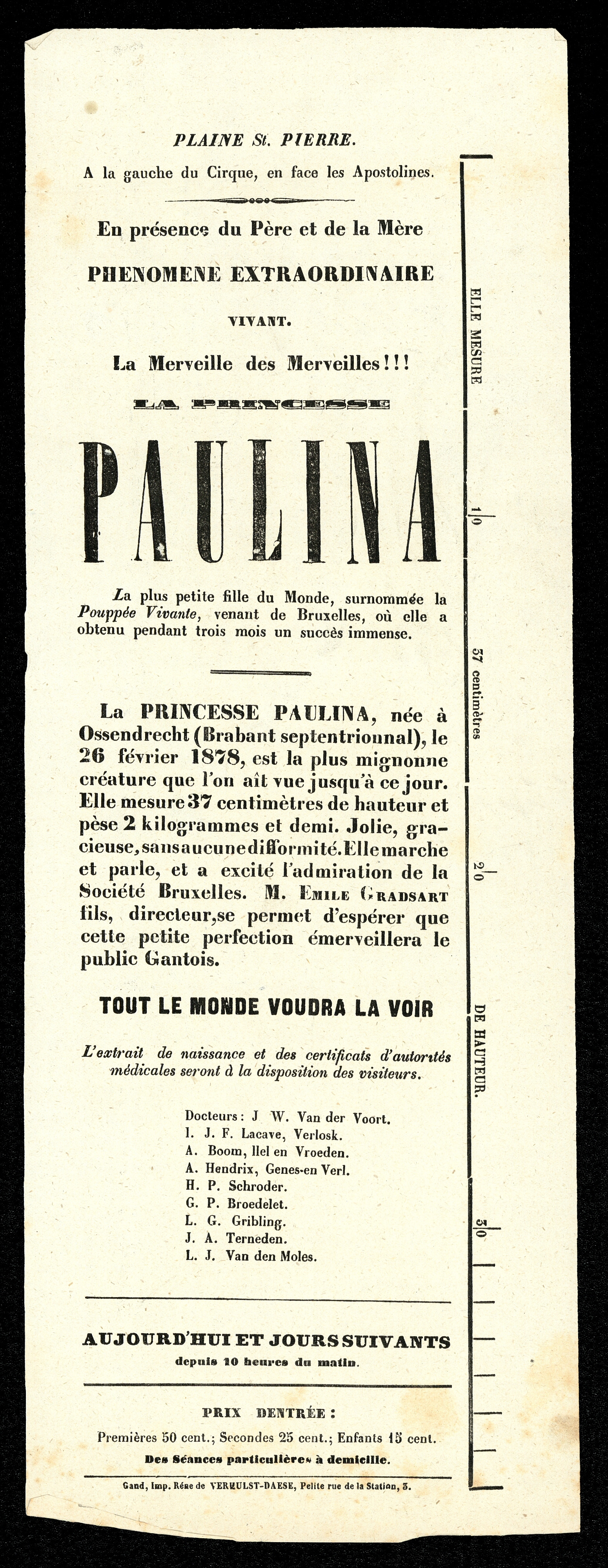

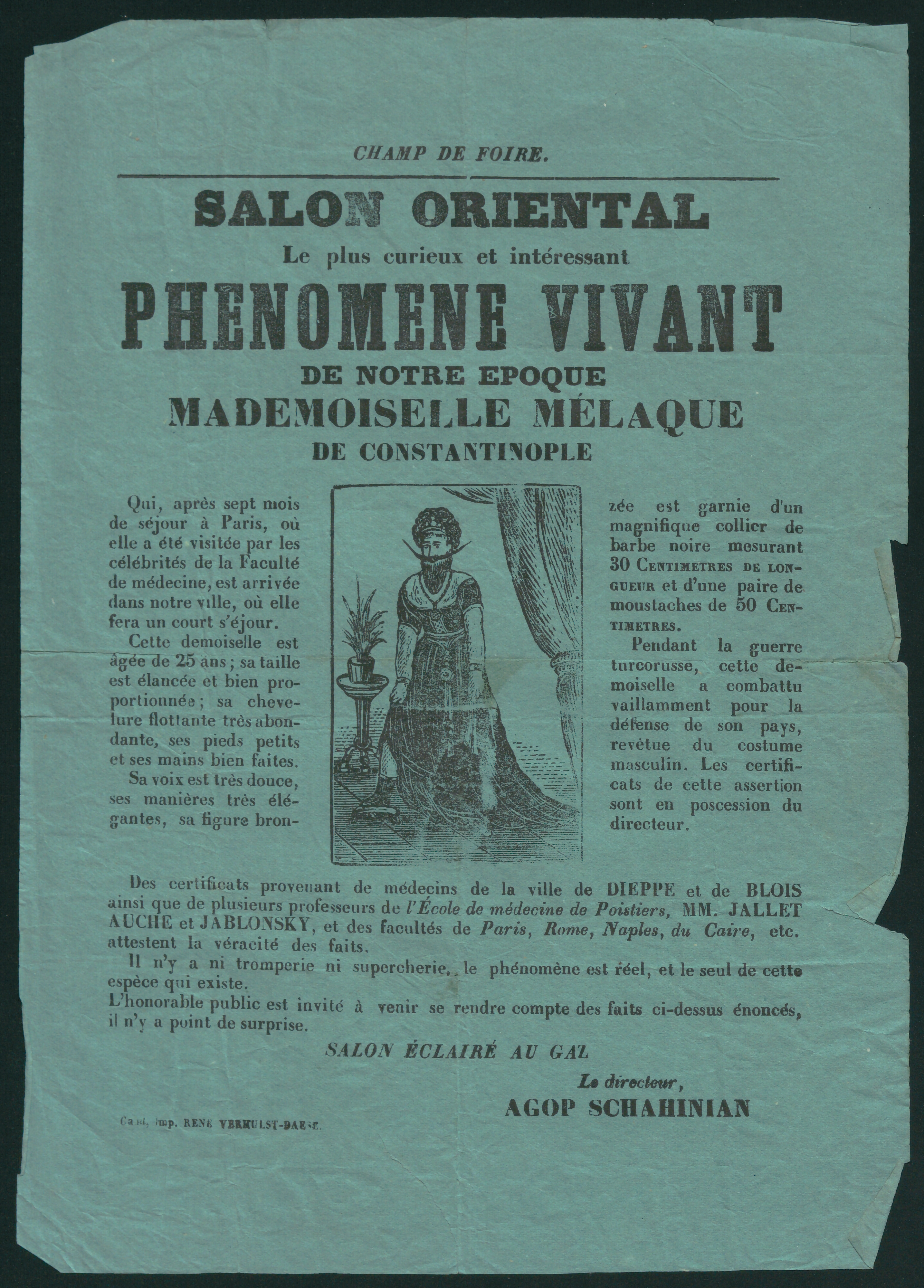

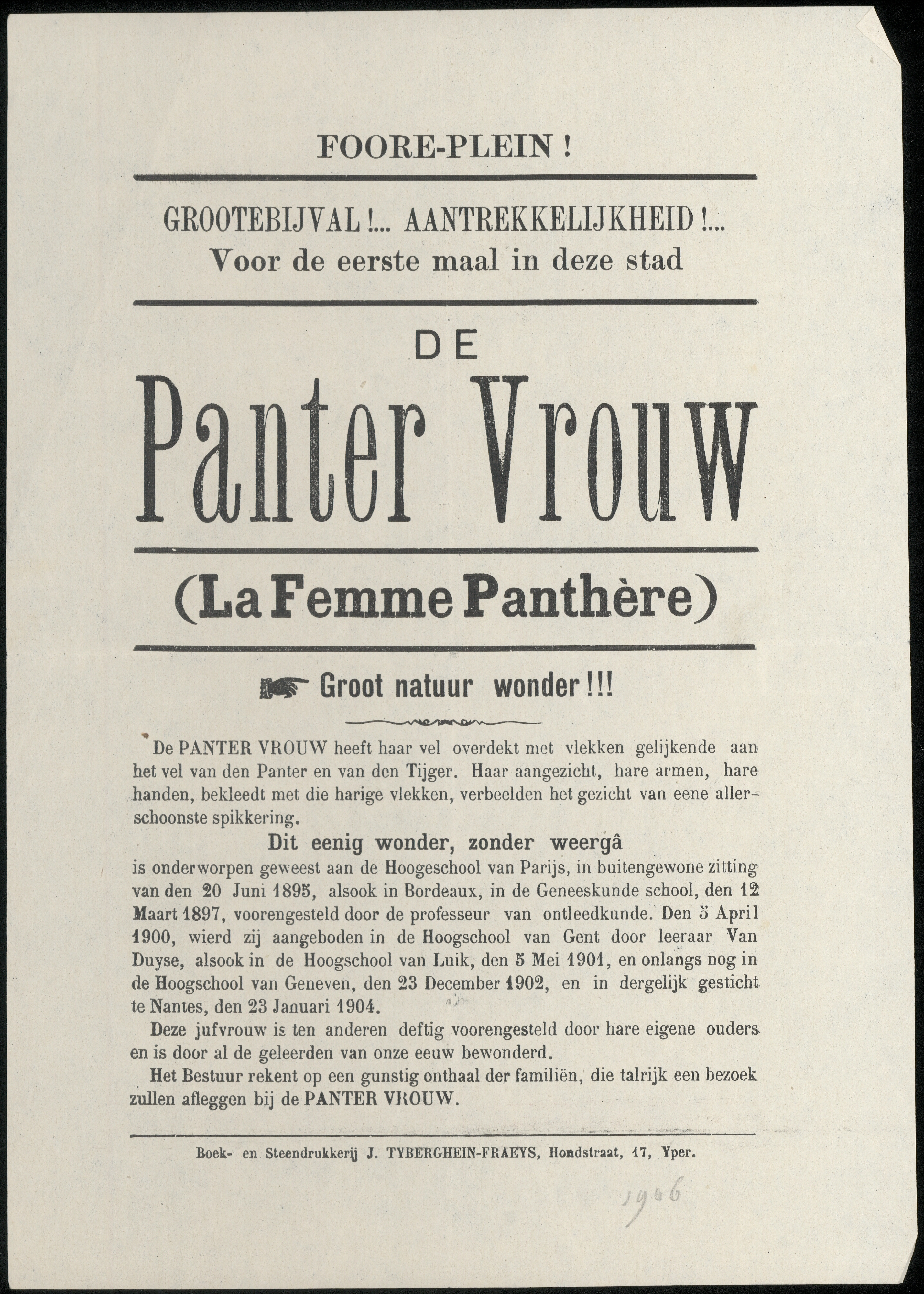

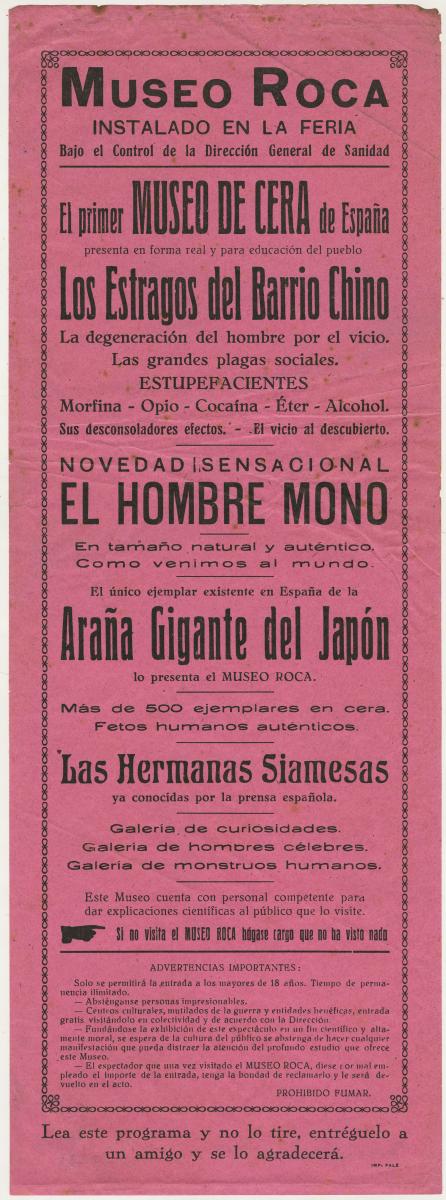

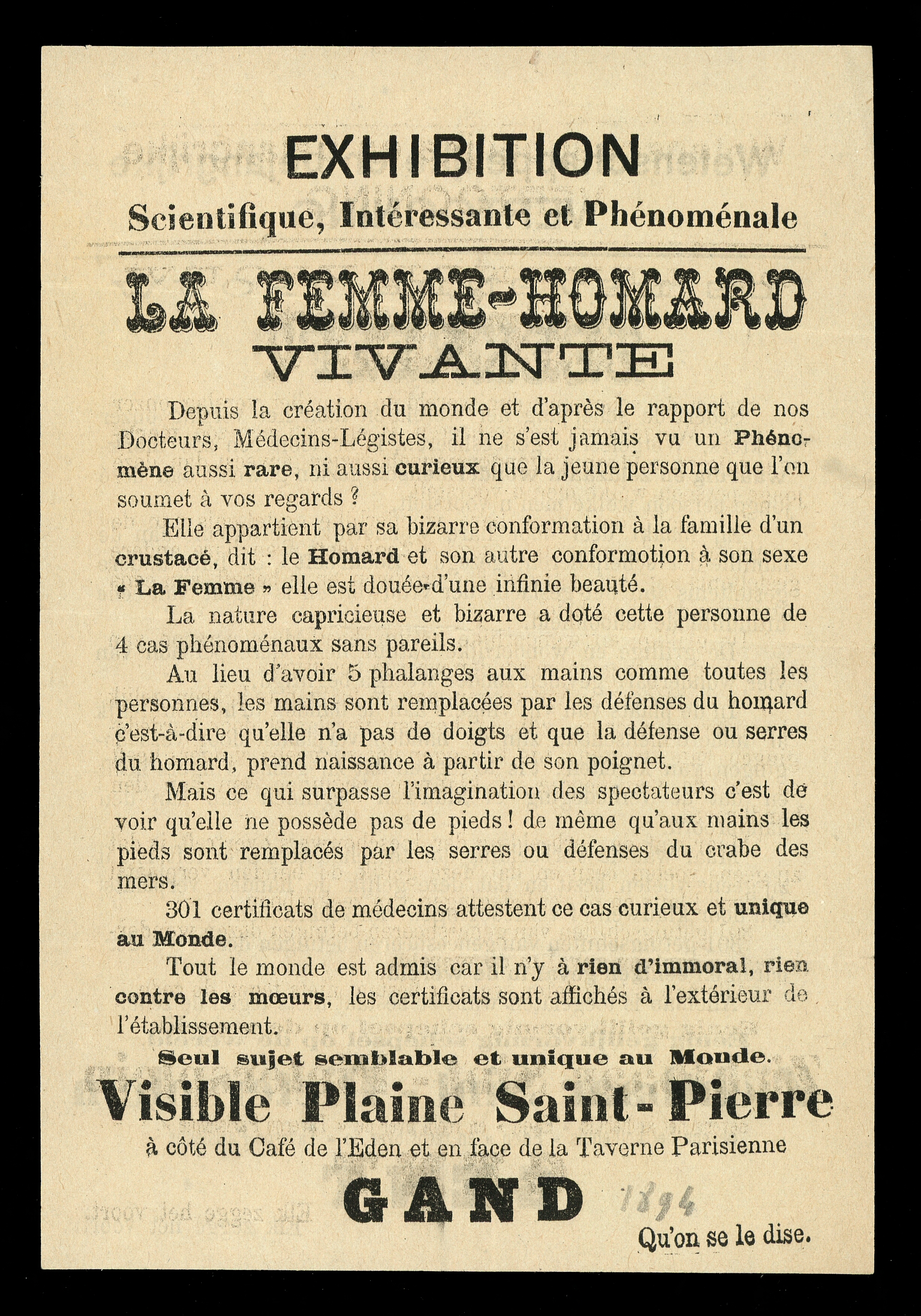

'Freaks' of nature, living wonders, and phenomena

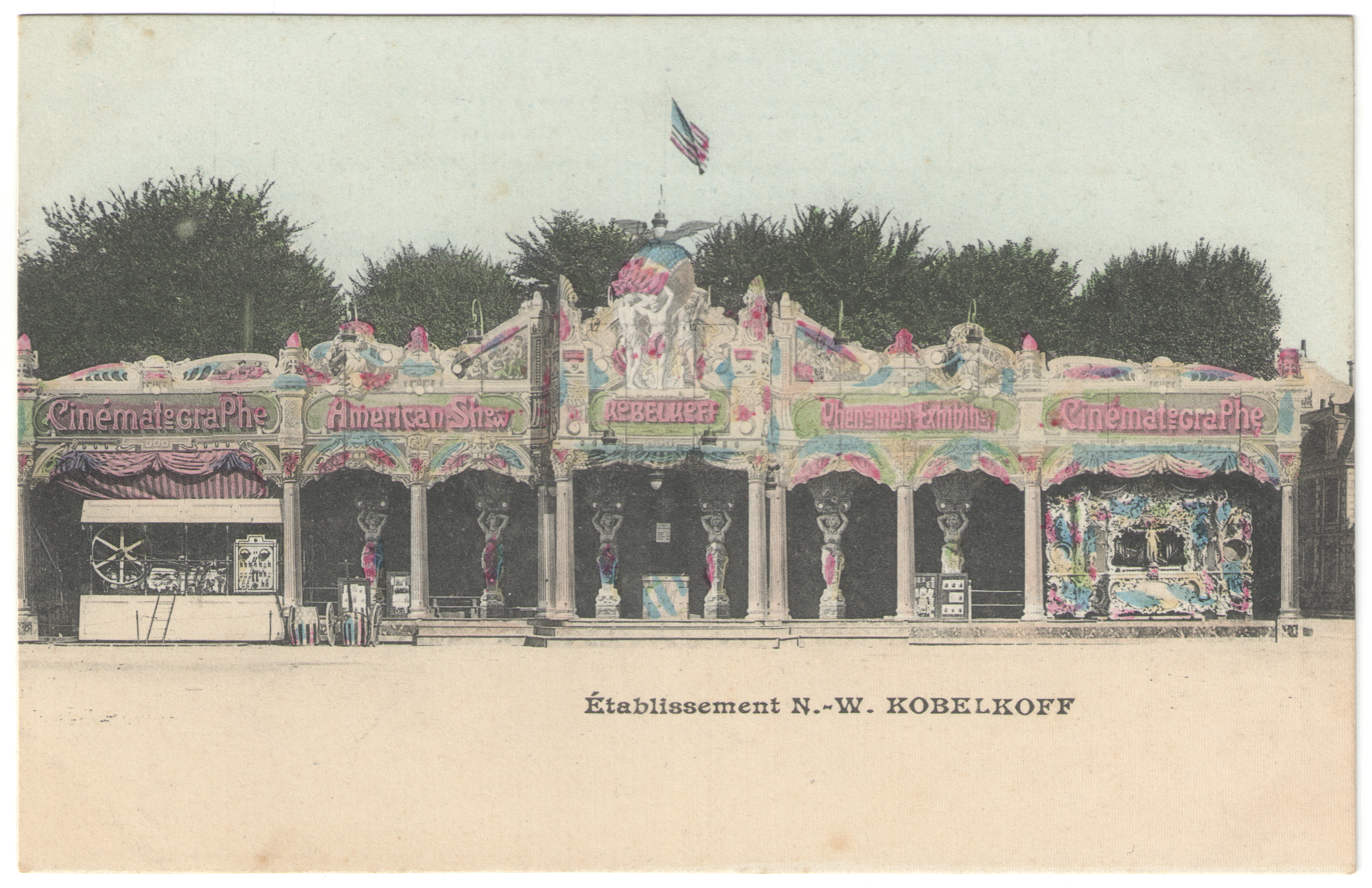

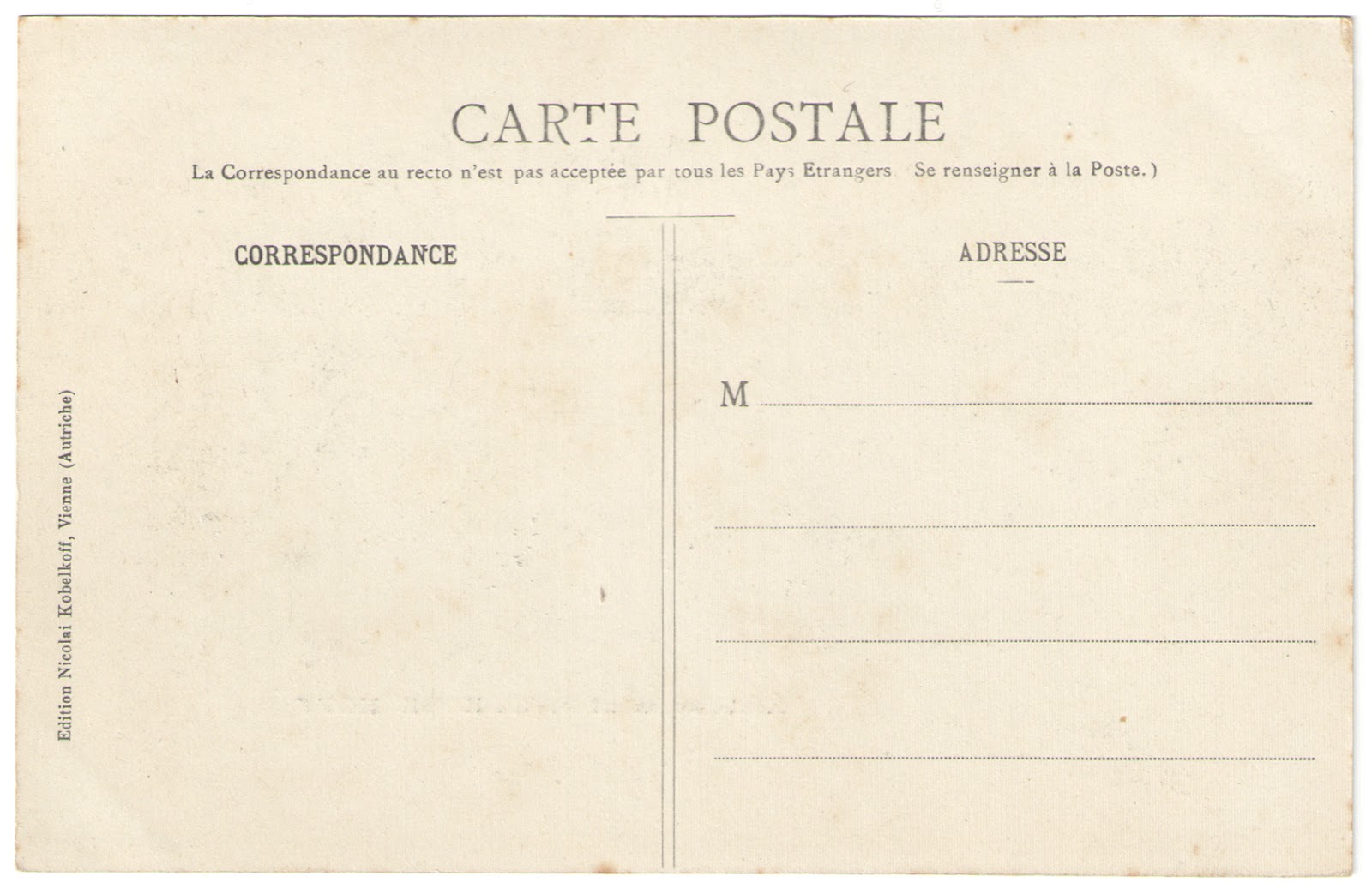

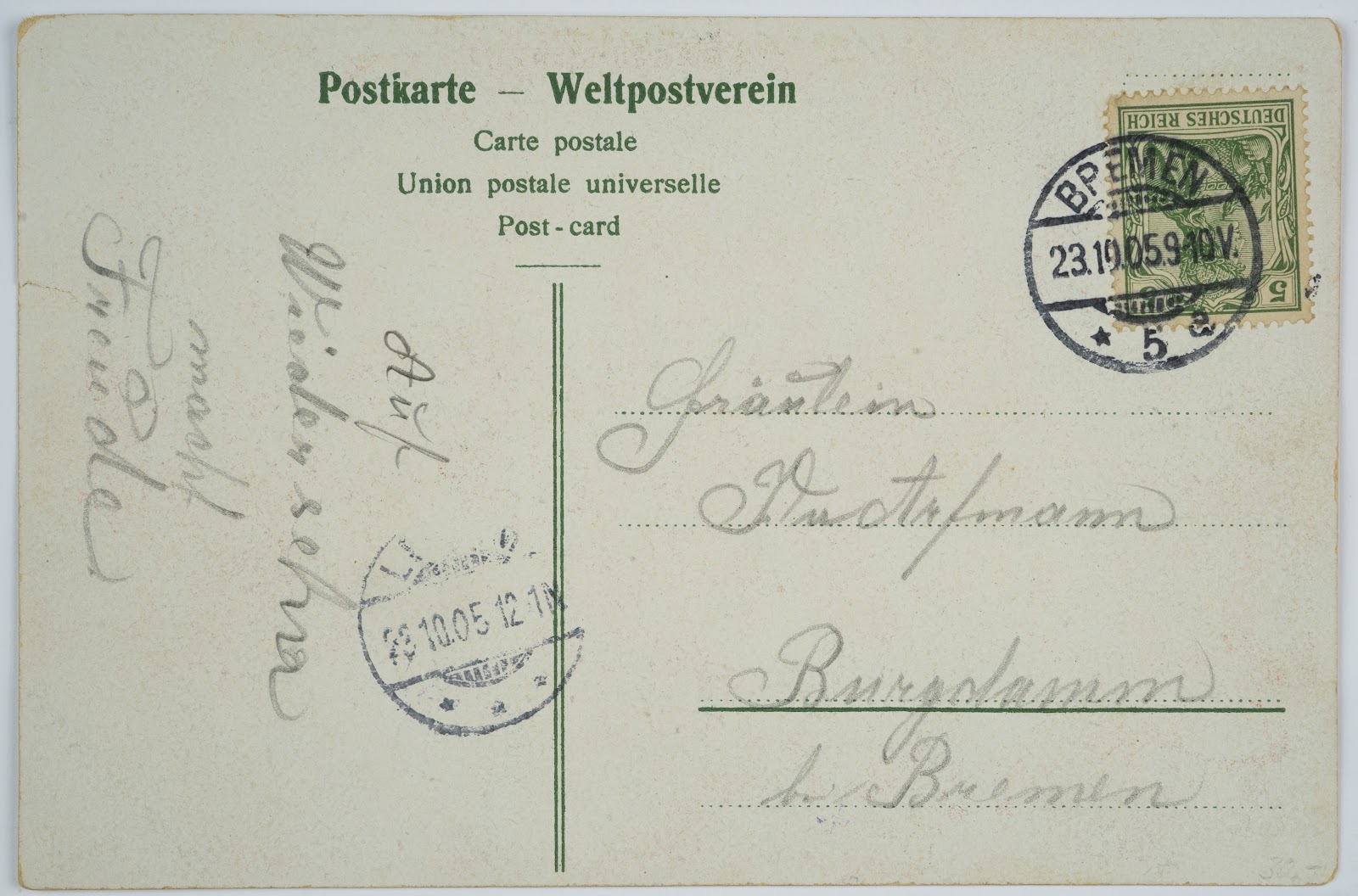

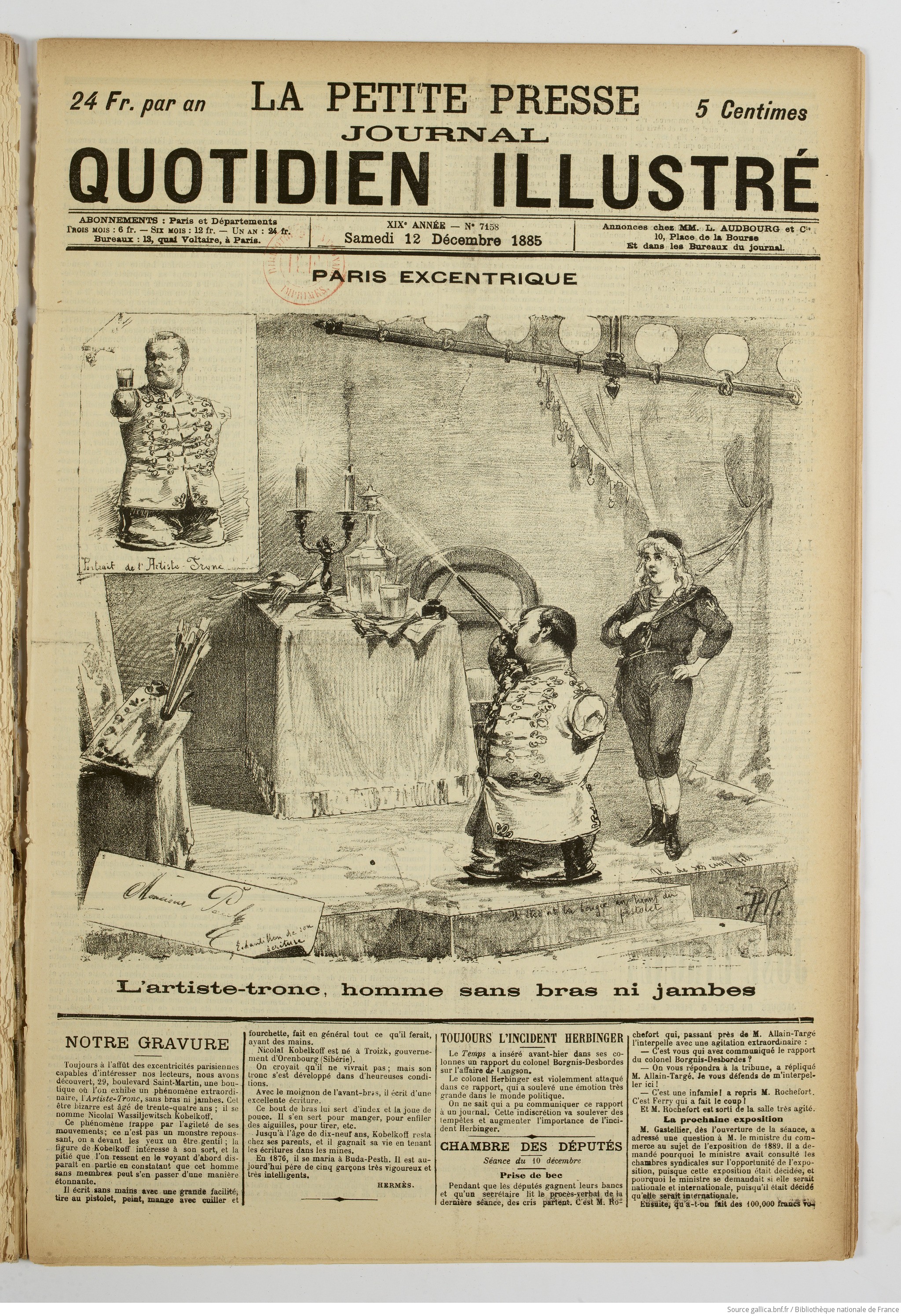

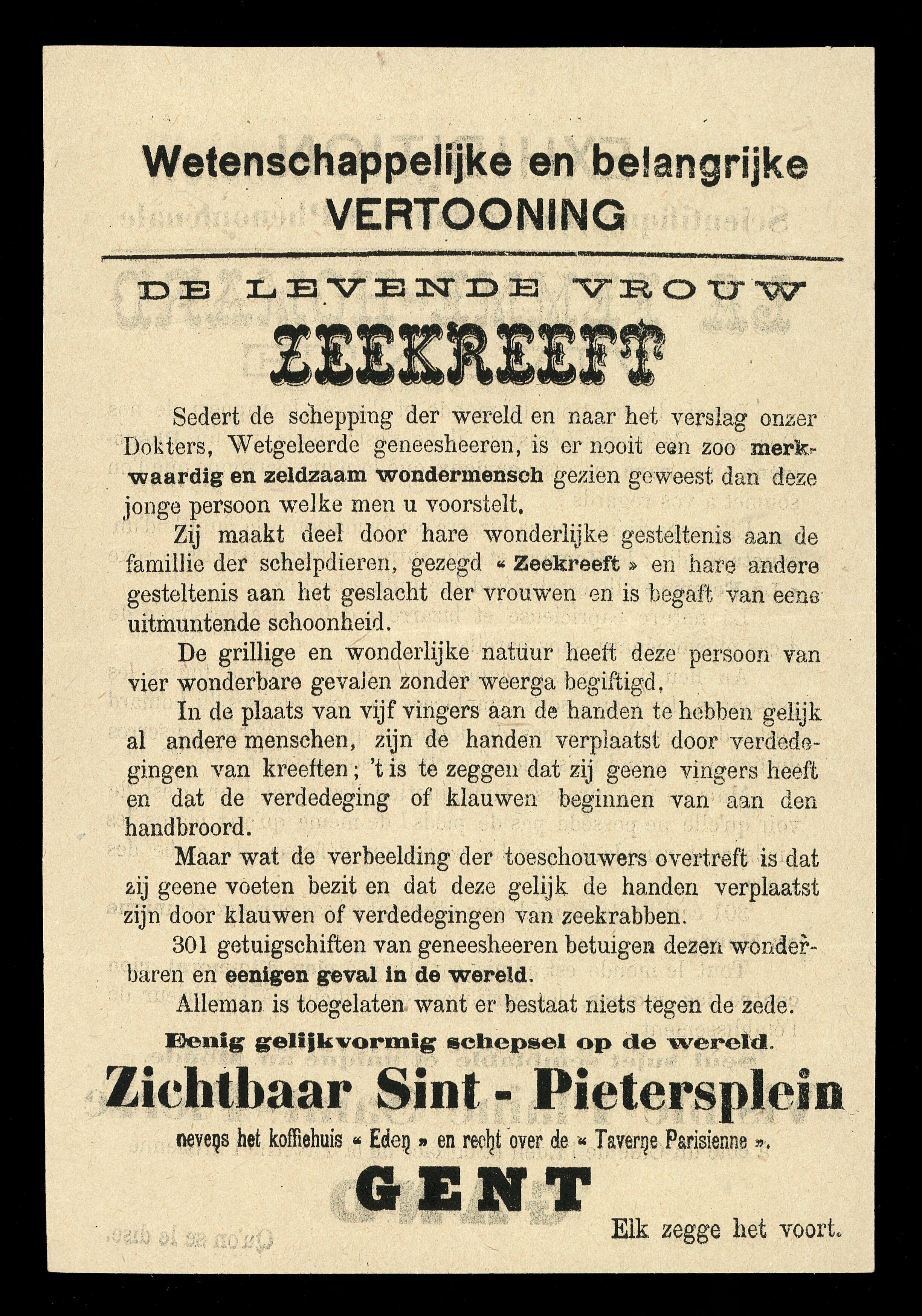

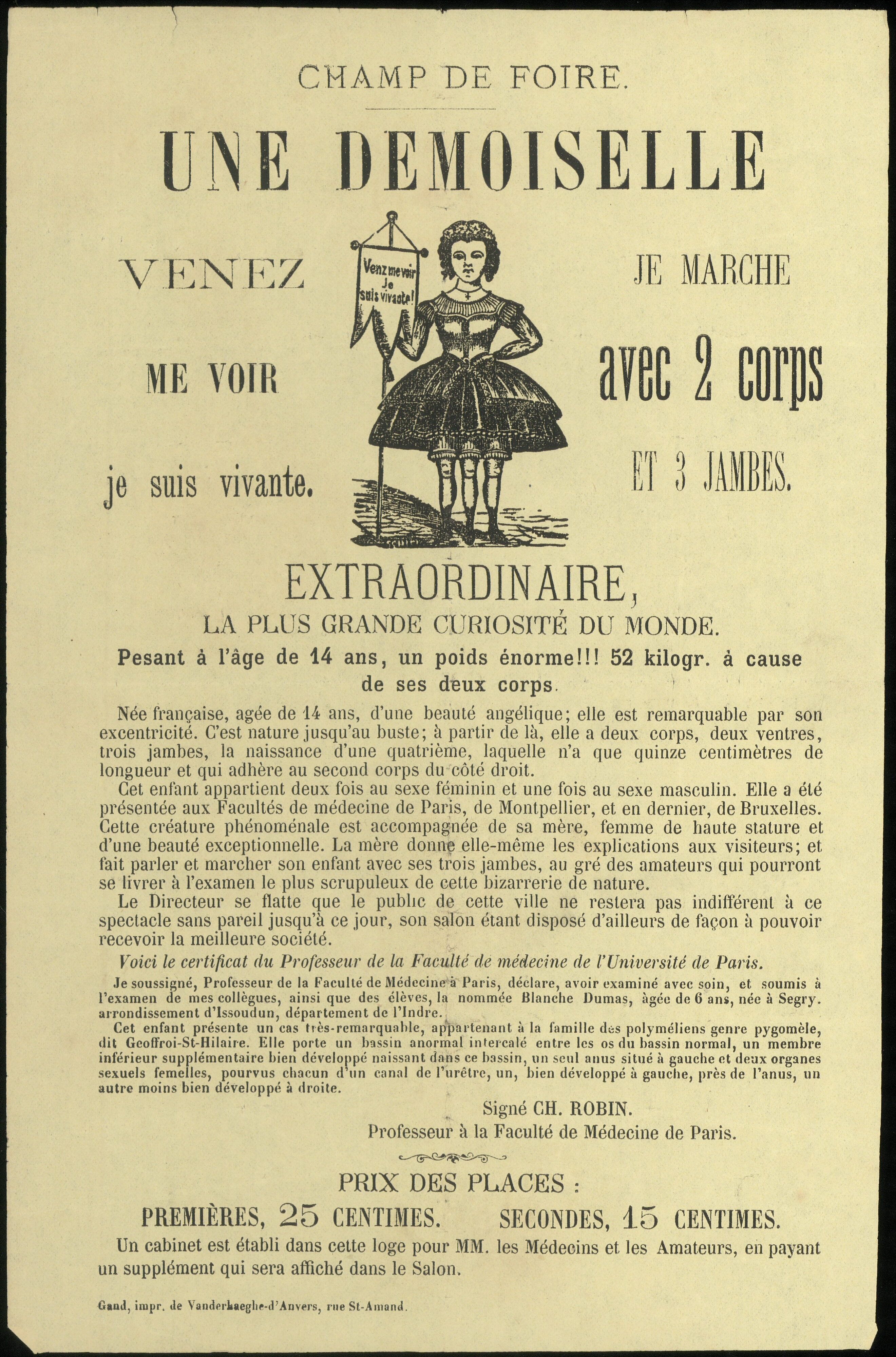

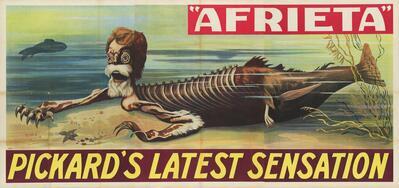

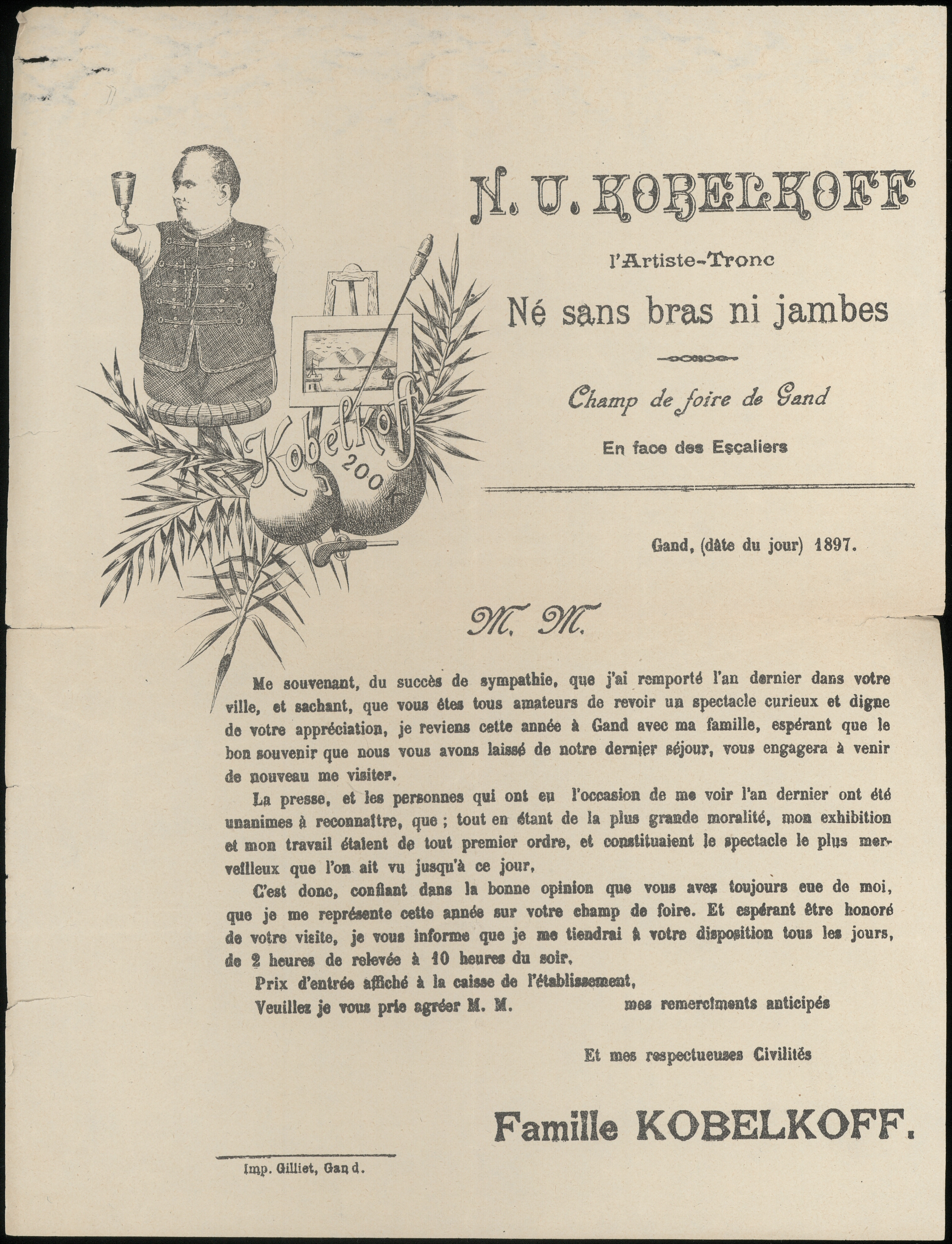

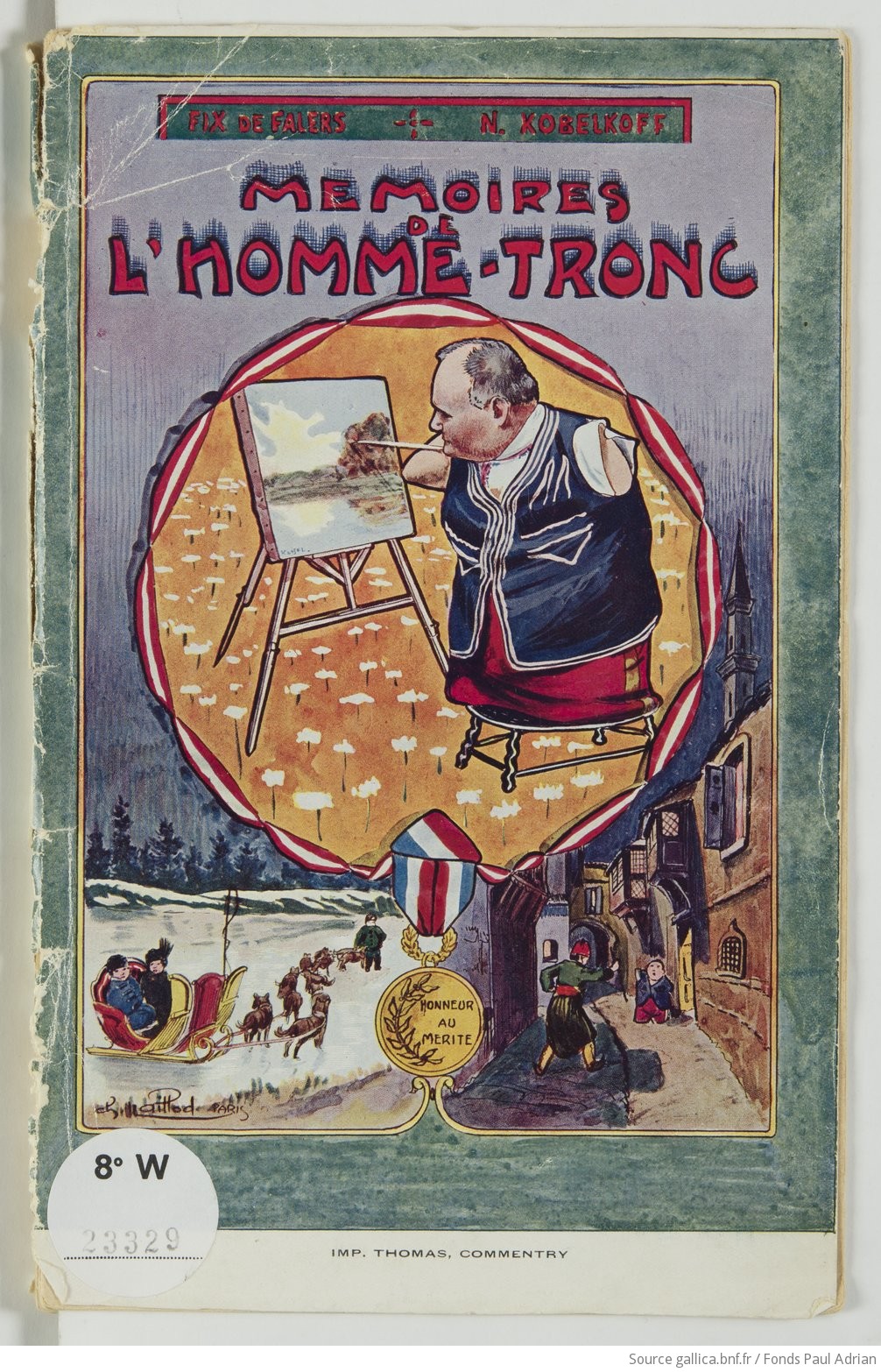

Who and what could be seen in the so-called 'freak' shows? Circus and fairground performers often made a distinction between people with congenital disorders and those with acquired exceptionalities. The latter category included sword swallowers, hypermobile 'snake people', or people with a fully tattooed body. These artists created their unique appearance themselves through exercise, body modification, or special talents. Others, like Kobelkoff, were born with a body outside of the norm and used their physical situation to make a living. Such a division seems to imply that for people with congenital conditions, their identity was an inevitable consequence of their bodies. However, the figure of the 'freak', even then a contested term, is a cultural construct, created by the way society views the body.

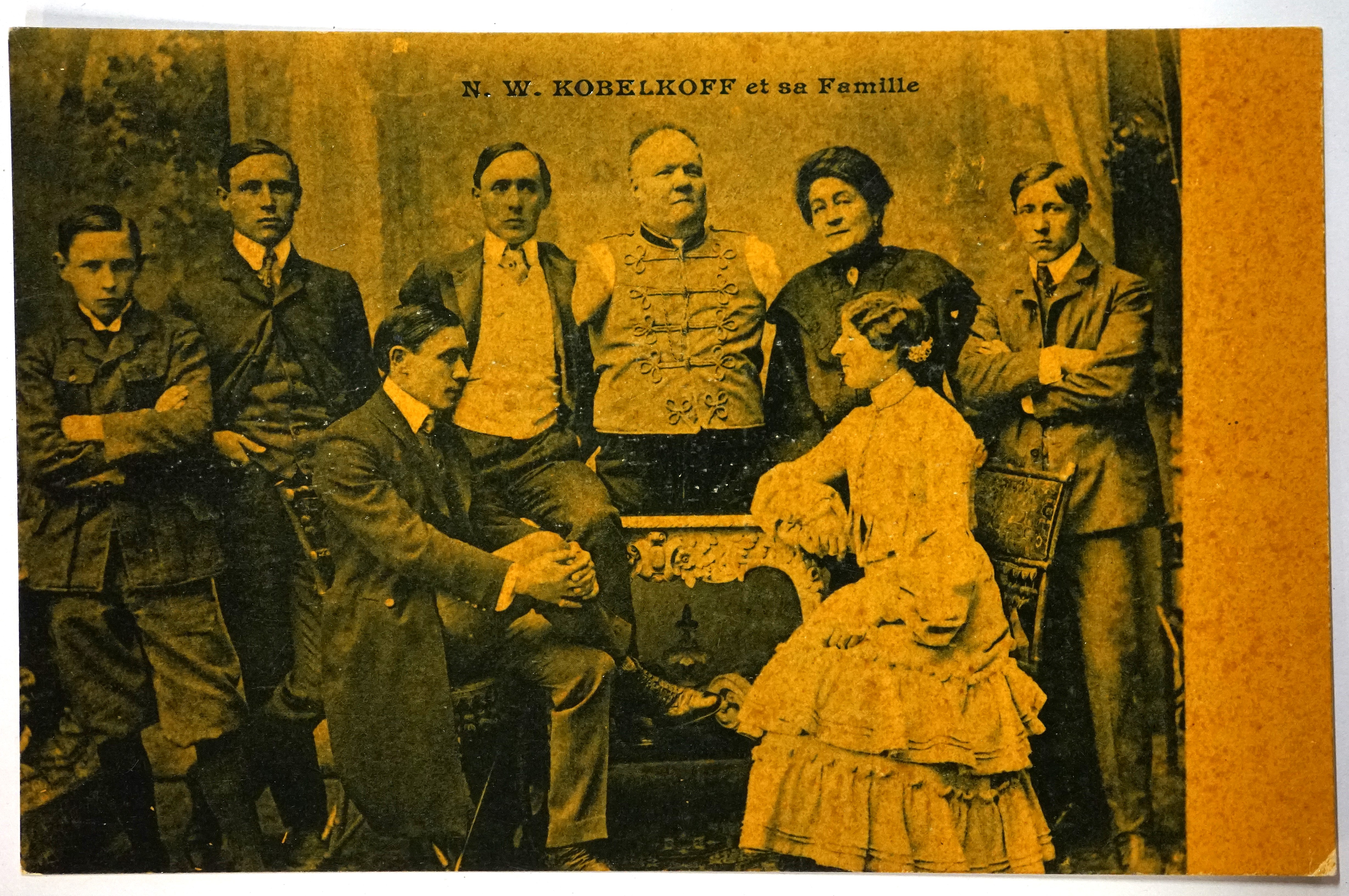

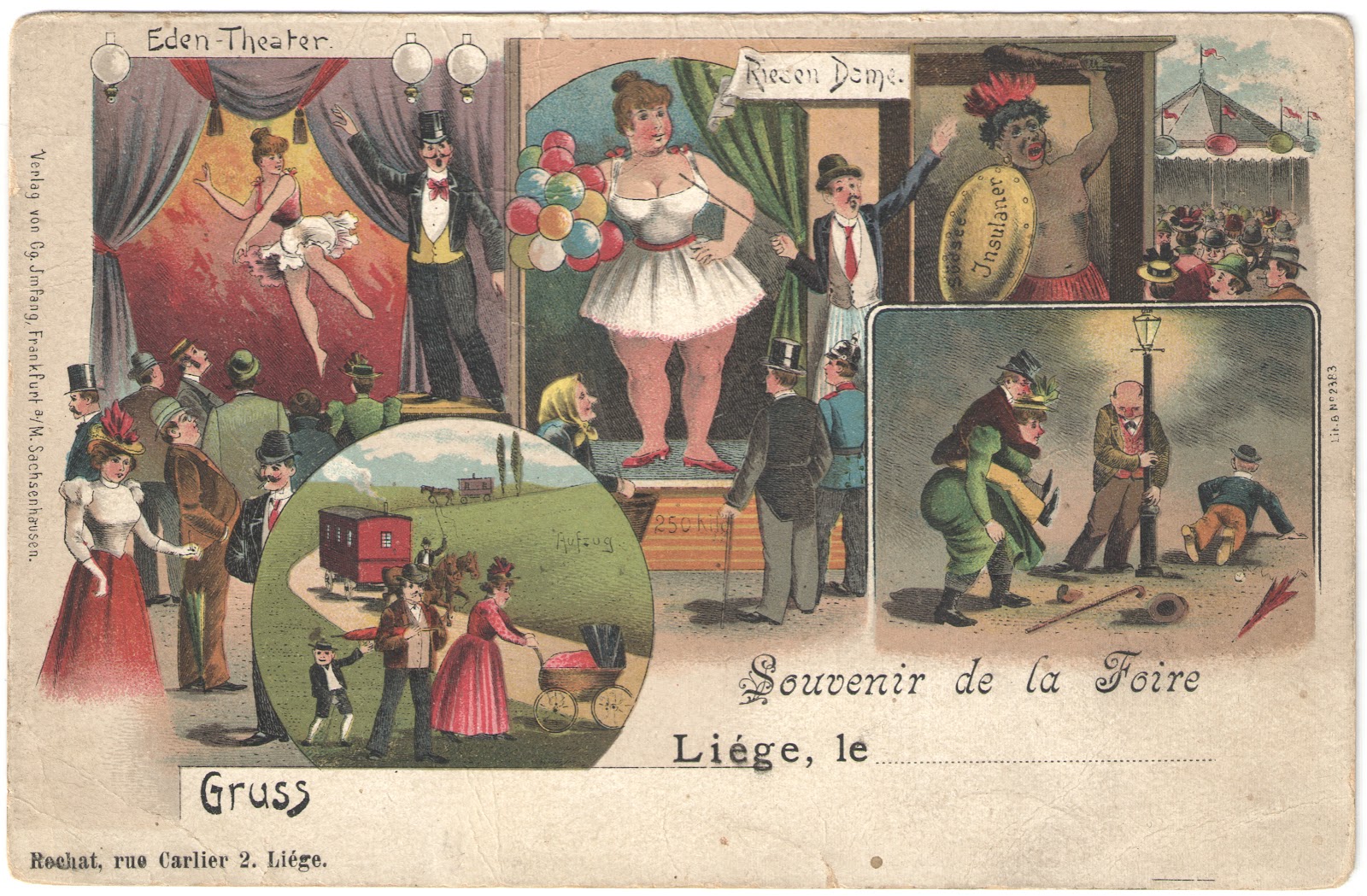

These shows tell us how nineteenth-century society gave meaning to physical differences. Today, we use terms like 'disability' or 'disorder', while someone from the fifteenth century would perhaps have regarded physical deviation as a divine harbinger of either prosperity or misfortune. The nineteenth century cast off those superstitious interpretations and looked to science for answers. The bodies put on stage challenged the limits of the socially imaginable. For instance, conjoined twins raised questions on individuality, while the bearded woman created doubts about the strict division between men and women. Historians therefore interpret these exhibitions as a mechanism through which spectators could construct their own identities as modern citizens. By putting these 'extraordinary' people on stage and singling out what was different about them, the audience defined itself as the norm.

Related Sources

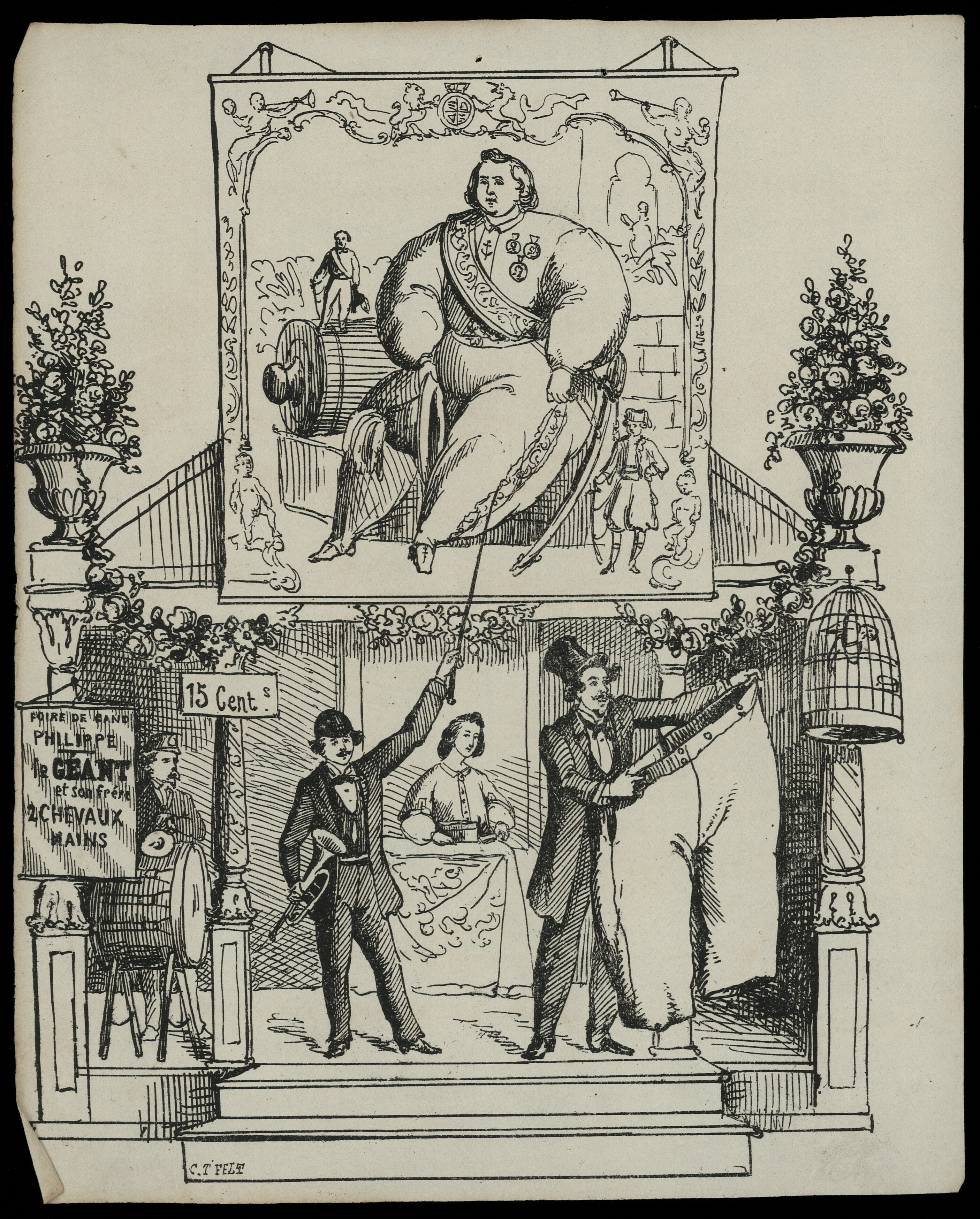

souvenir de la foire de Gand: Album comique, 1865 (Illustration)

Explore the database

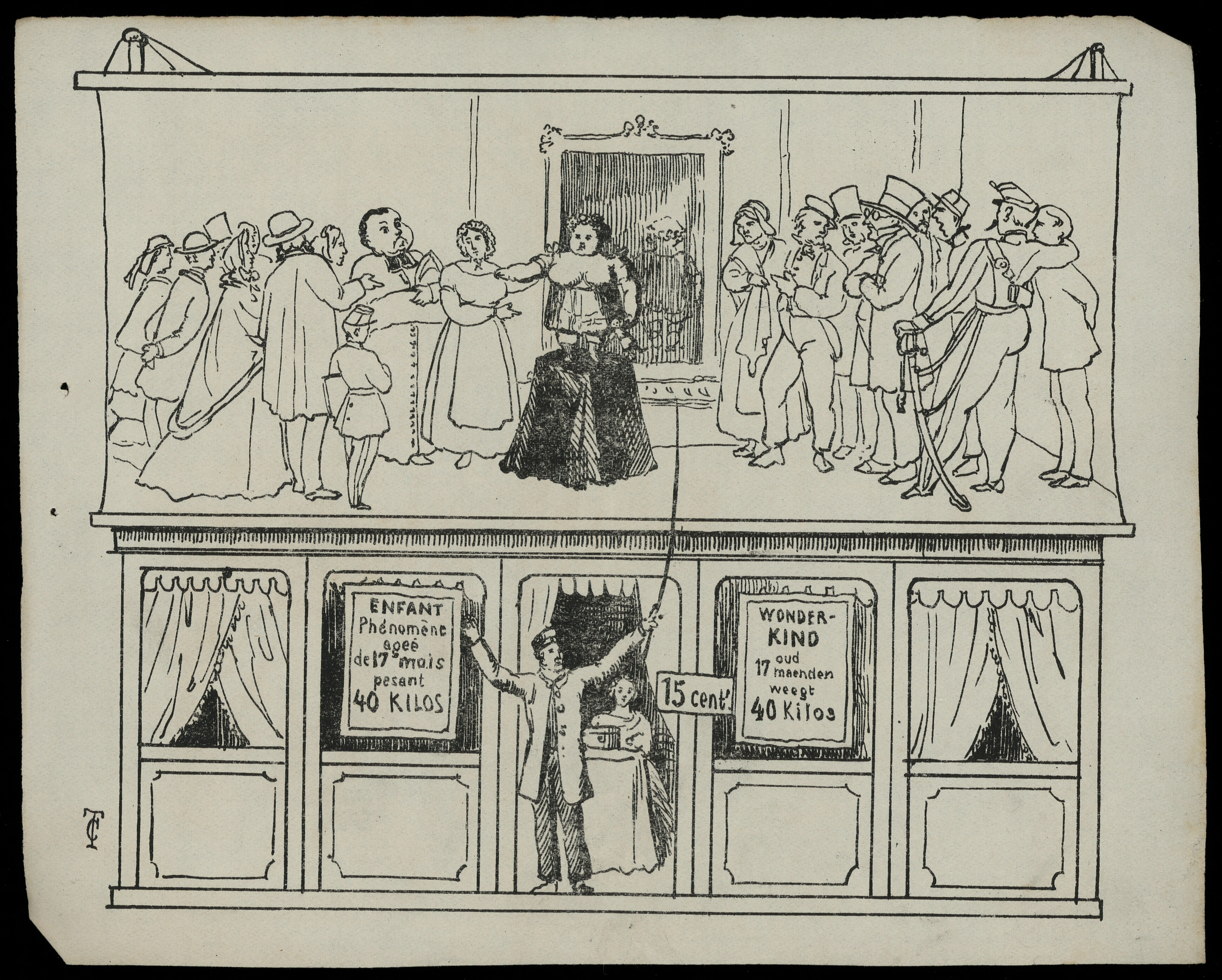

Phénomenes (Illustration, 1830)

Explore the database

souvenir de la foire de Gand: Album comique, 1865 (Illustration)

Explore the database