Professor of Dog Studies

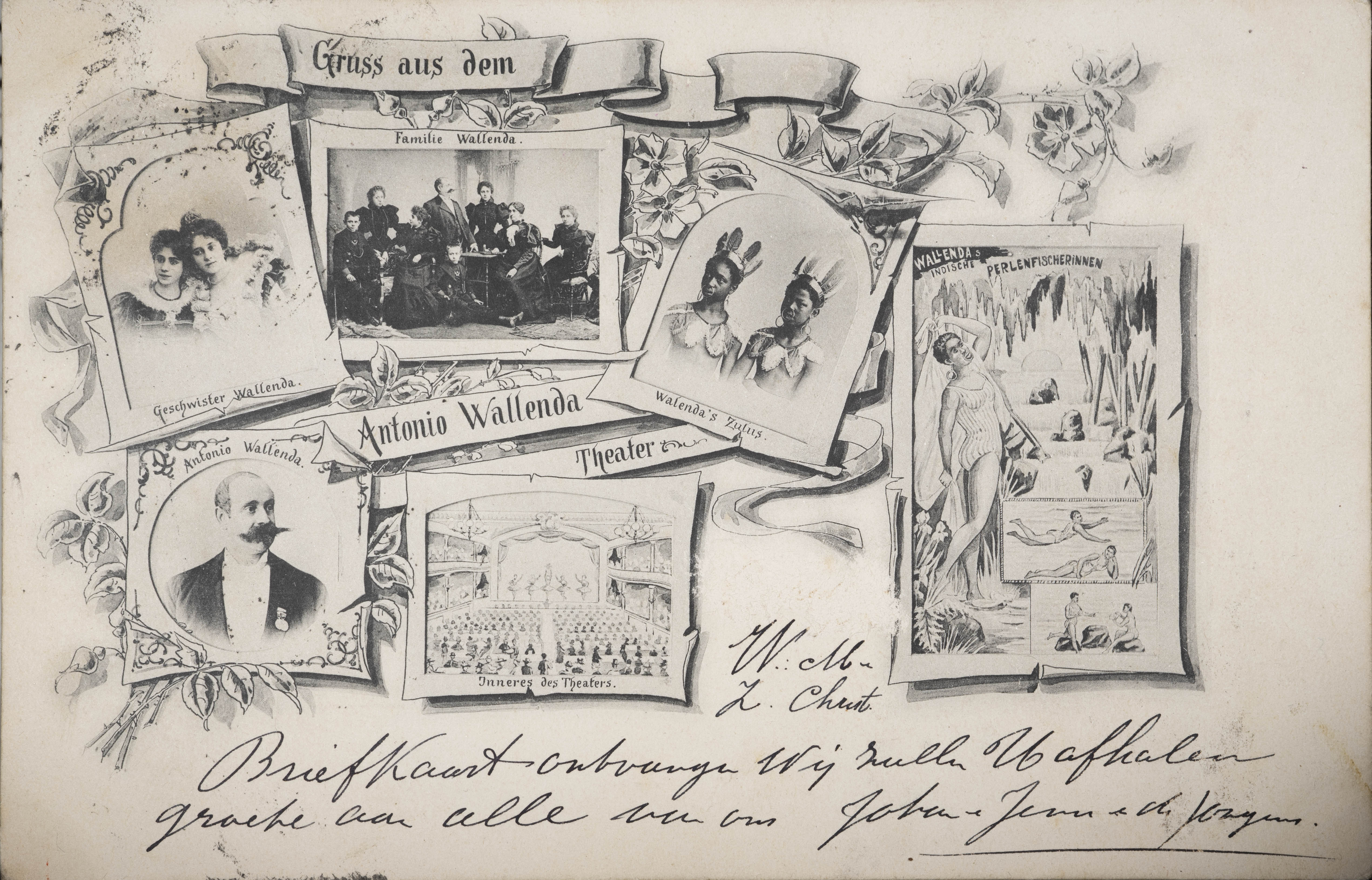

Antonio Wallenda grew up in an itinerant artist family from Austria-Hungary with a rich history dating back to the eighteenth century. He developed an early fascination with animals and their behaviours. His father, an itinerant theatre director, introduced him to the world of the fairground and spectacle. Antonio Wallenda's first venture in Bavaria, a cabinet full of mechanical automata, went up in smoke due to a fire. However, this setback proved to be a turning point: Young Wallenda decided to focus on training live animals from then on. He proudly called himself 'professor of cynology', the study of dogs, based on his insights into the complexities and peculiarities of dogs.

At the time, dog training was mainly focused on smaller breeds such as poodles, but Wallenda decided to experiment with imposing Ulmer dogs, known for their size and intelligence. This proved to be a brilliant move. His shows soon attracted the attention of international audiences, who were full of admiration for his dogs' discipline and human-like skills. The press praised his innovations and devoted illustrated articles to his remarkable training experiments. As a result, the theatre quickly expanded its repertoire to include a range of other smart animals, such as geese, cats, cockatoos, and, at one point, even elephants.

Related Sources

A clever marketing strategy

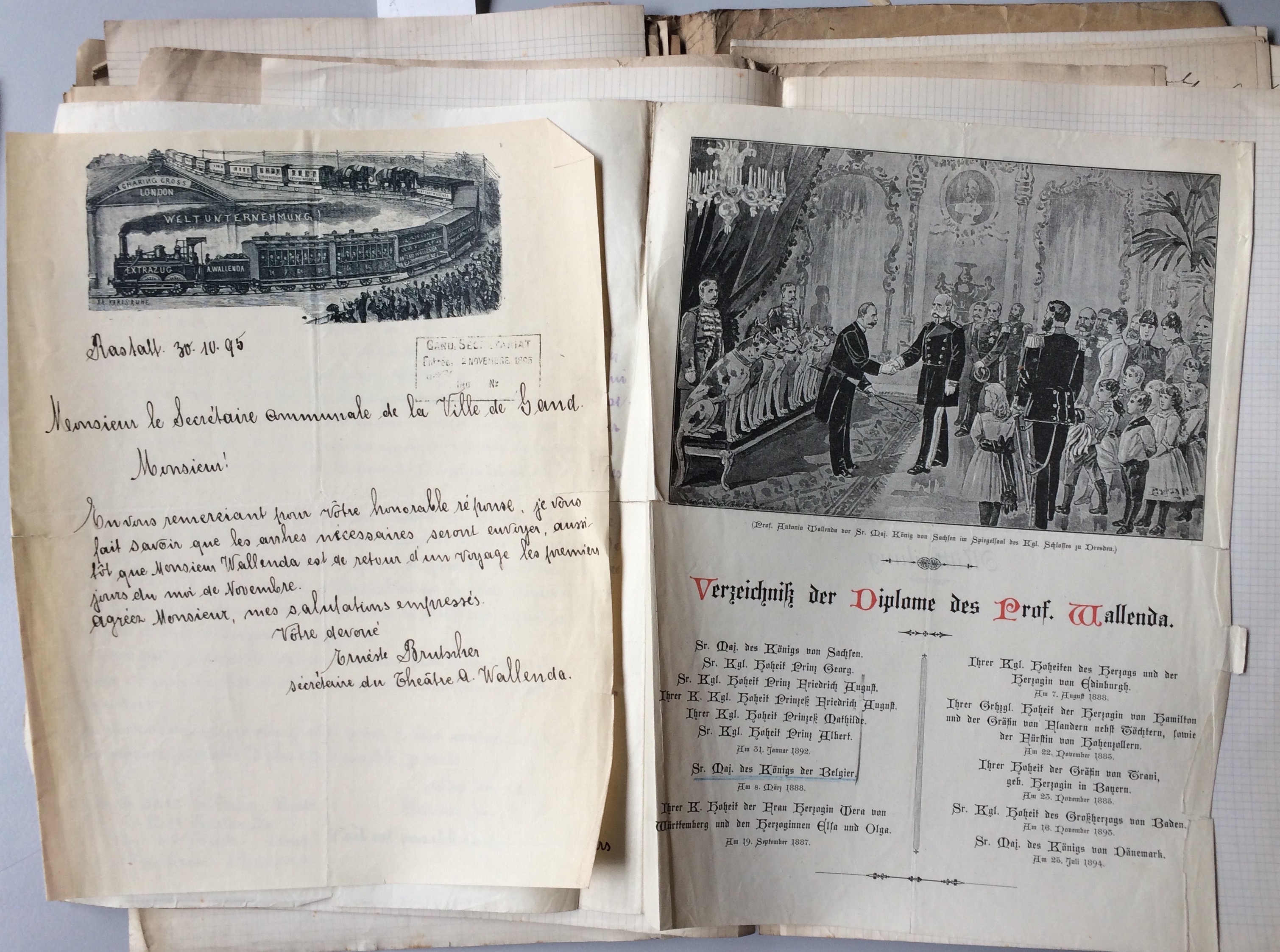

Wallenda understood that his success at the fairground not only depended on the quality of the shows, but also on clever self-promotion. He introduced himself as a scientist and published a manual called Praktisches Handbuch für Hundeliebhaber (Practical Manual for Dog Lovers), in which he described his methods and philosophy, profiling himself as an expert in animal welfare and training. In his advertisements, he invariably cited his many titles and awards, including a ring from Albert, King of Saxony, and compliments from the king of Belgium. His promotional materials listed no less than 26 diplomas and certificates, confirming the alleged recognition and praise he would have received in his career.

This self-promotion as a professor was appropriate at a time when audiences were becoming increasingly interested in science. Wallenda's shows were more than just entertainment. They were a form of education, showcasing animals as intelligent beings capable of learning and cooperation. This reflected the scientific interests of the time, in which Darwin's theory of evolution and studies of animal behaviour received much attention. By having his animals perform human tasks, Wallenda encouraged his audience to think about the relationship between humans and animals, and the capabilities of animals.

Related Sources

Humans and animals at the theatre

The emergence of Darwin's theory of evolution had fundamentally changed the way people viewed animals and the relationship between animals and humans. The extent to which animals possessed intelligence and what skills distinguished them from humans were hotly debated topics. Wallenda's performances addressed this in a playful way: By having animals perform human tasks, he bridged the gap between science and spectacle. Wallenda's shows presented animals as clever entertainers, as creatures that could learn, cooperate, and perform human tasks: marching like soldiers, putting out a fire, or delivering letters.

However, these shows were not an isolated phenomenon. Other fairground theatres and circuses were experimenting with similar formats, such as Delafioure's Théâtre des Animaux Savants, where dogs, monkeys, and cats in human attire performed daily tasks. At a time when society was grappling with new understandings of the natural world, animal theatre lent a visual and accessible form to these ideas. At the same time, the shows affirmed human superiority: However impressive the animals' feats were, they were also proof of human control over nature.

Related Sources

A European success story

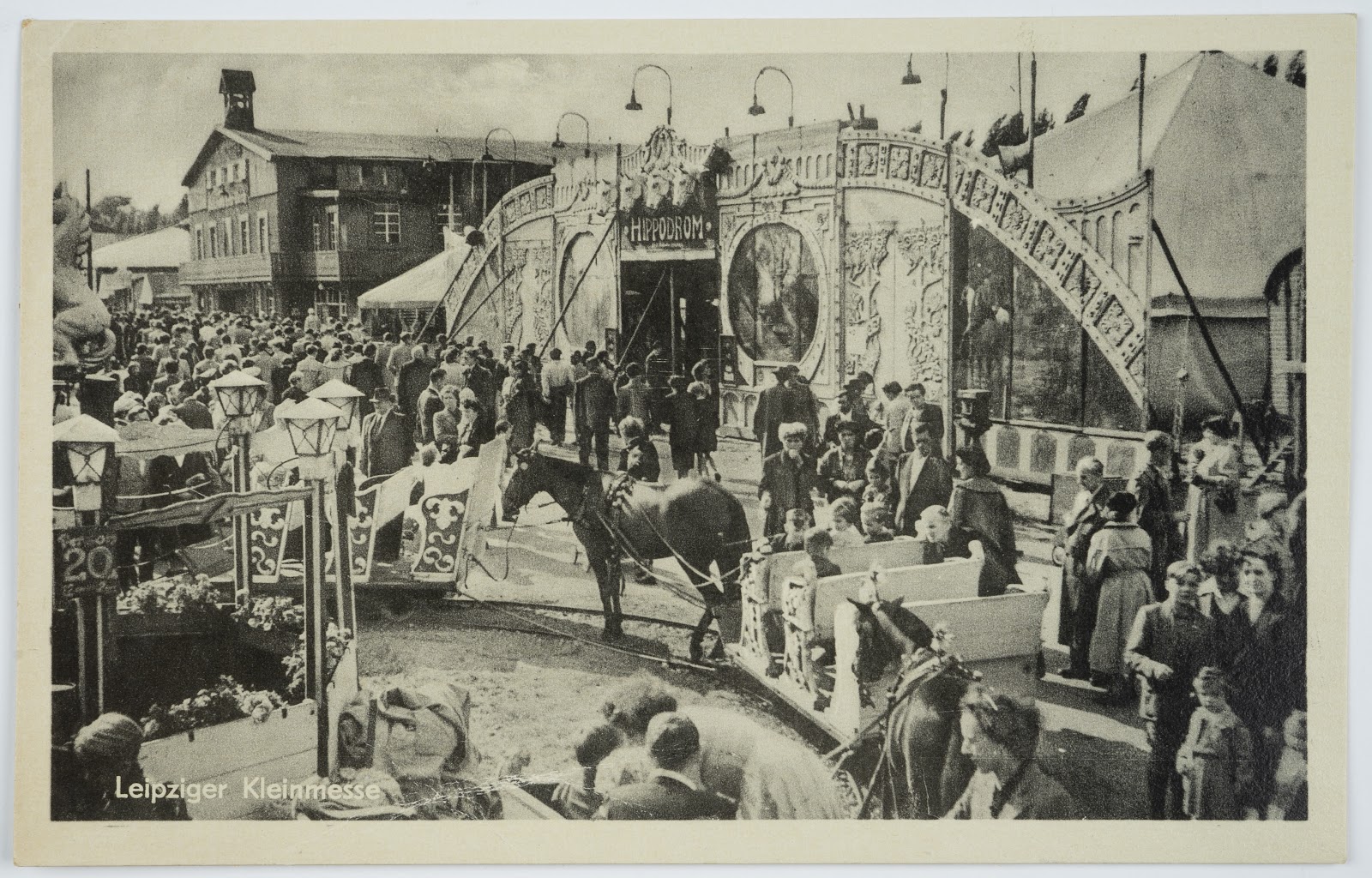

The Wallenda Theatre drew packed venues in cities such as Antwerp, Paris, London, Vienna, and Saint Petersburg. The shows' enormous popularity also had an economic impact: Local newspapers reported how the arrival of the Wallenda Theatre significantly increased the number of visitors, which in turn proved beneficial to local merchants. But Wallenda's success also had a downside. The intensive tours and reliance on complex logistics put Wallenda's business under pressure. For instance, on several occasions, he suffered heavy losses due to storms and fires, including a devastating blaze in Antwerp. Yet he managed to recover each time, driven by his passion for animals and entertainment.

Wallenda's programme was as diverse as his audience. Besides animal acts, it included theatrical and acrobatic feats. A show in Liège in 1896 opened with grand pantomime spectacle La fête du jour de l’an à Peking, which depicted an impressive Chinese New Year's celebration. With eighteen jugglers, soldiers in shining armour, and dazzling costumes made in Paris, Wallenda staged a spectacle that capitalized on audiences' fascination with exoticism. This was typical of nineteenth-century fairground culture, in which Western representations of other cultures were performed as educational entertainment.

Wallenda's legacy

Although Wallenda was less well-known after his death than contemporaries such as the American P.T. Barnum, his theatre leaves behind a complex cultural legacy. It shows the boundless imagination of the fairground, but also emphasizes how entertainment mirrors broader social developments. Wallenda's shows played a significant role in popularizing scientific ideas, explored the boundary between humans and animals, and affirmed cultural stereotypes.

His legacy invites us to reflect critically. The nineteenth-century fascination with 'smart animals' echoed a desire to place animals in human categories, just as new scientific insights were incorporated into a worldview that still relied heavily on tradition. This shows how popular culture influences how we think about science, ethics, and the role of entertainment. The performances of Wallenda and his contemporaries remind us that entertainment is never mere amusement, but says something about the time in which it originated and the ideas that were prevalent then, just as contemporary entertainment continues to do today.

Related Sources

Further Reading

Nele Wynants. "Wallenda's Wonderful Performing Dogs: Challenges and Opportunities for a Transnational Circus and Funfair Historiography", Circus: Arts, Life and Sciences, vol. 3, no. 2, 2024, pp. 49-82, doi.org/10.3998/circus.4273.