From zoos to universal exhibitions

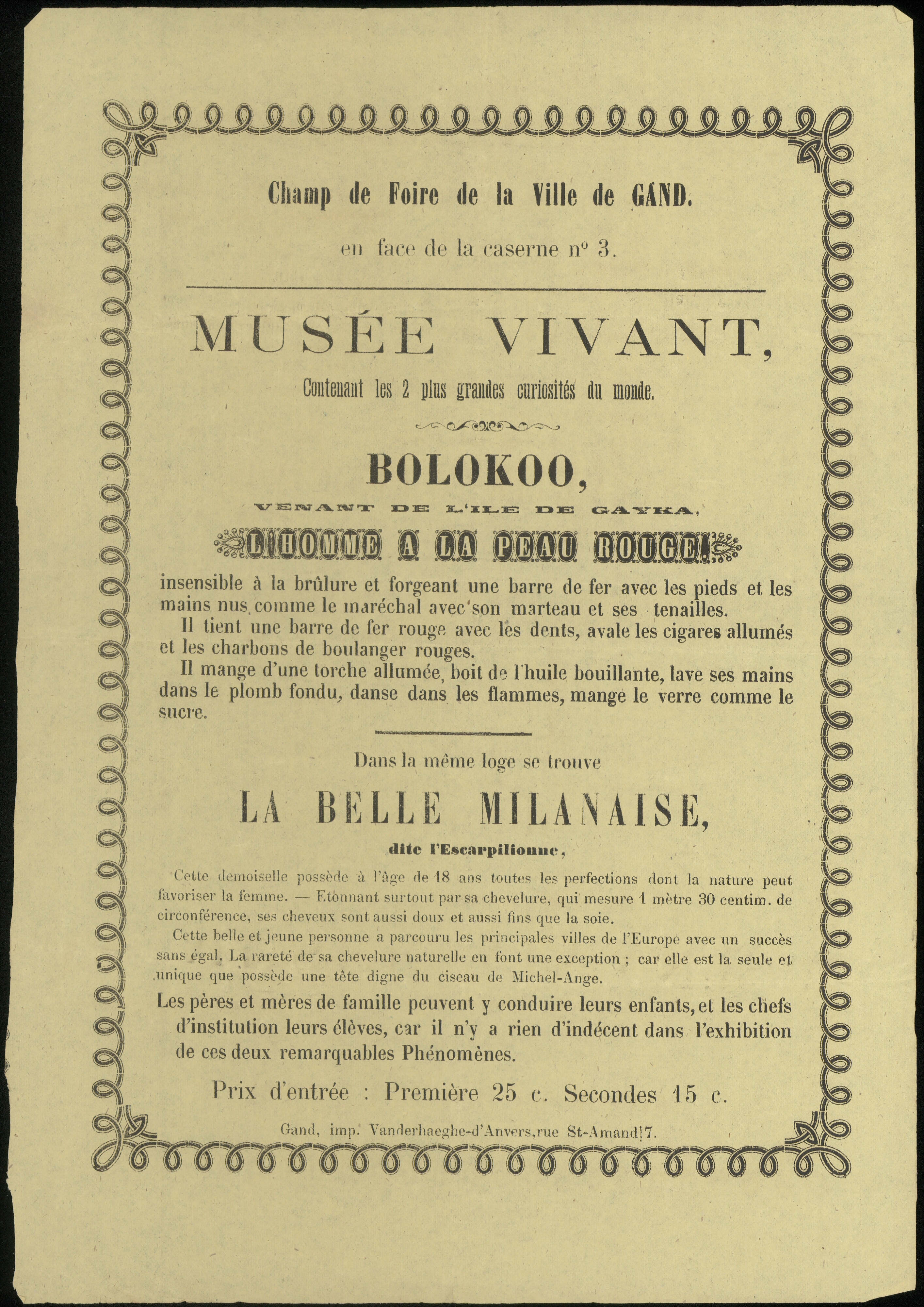

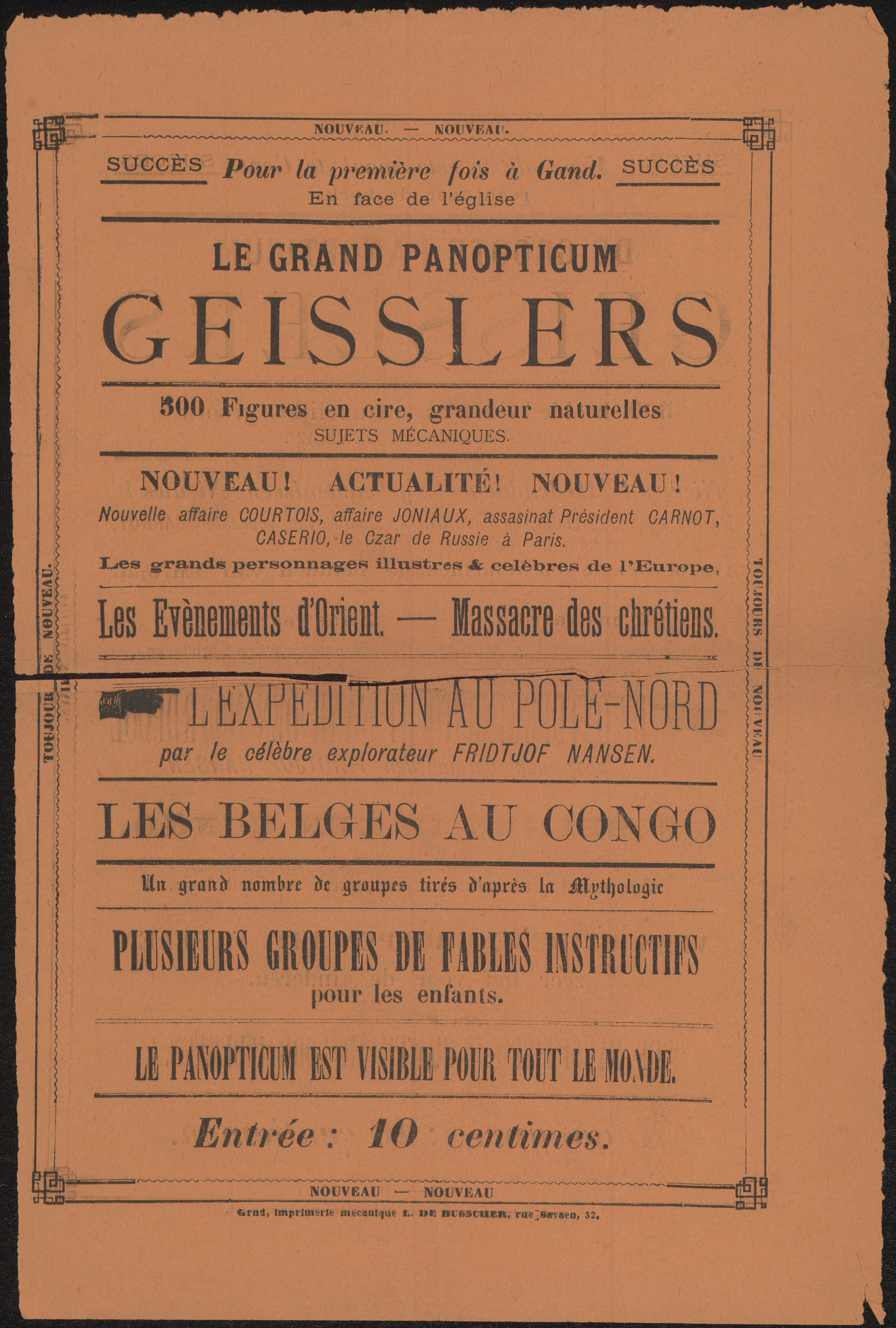

The programme of this fairground attraction reported that the artists were previously featured at the Paris Jardin d'Acclimatation: the Parisian amusement park of the same name in the Bois de Boulogne which still exists today. This park originated in 1860 as a zoo with mainly plants and animals from the French colonies but evolved into a space where humans were also exhibited. From 1877 to 1912, the park organized the ‘Acclimatation Anthropologique’, in which people from colonial territories were exhibited as a living attraction. This not only happened in France. German animal trader Carl Hagenbeck also travelled through Europe with his Völkerschauen: shows in which people from distant countries were presented ‘in their natural habitat’.

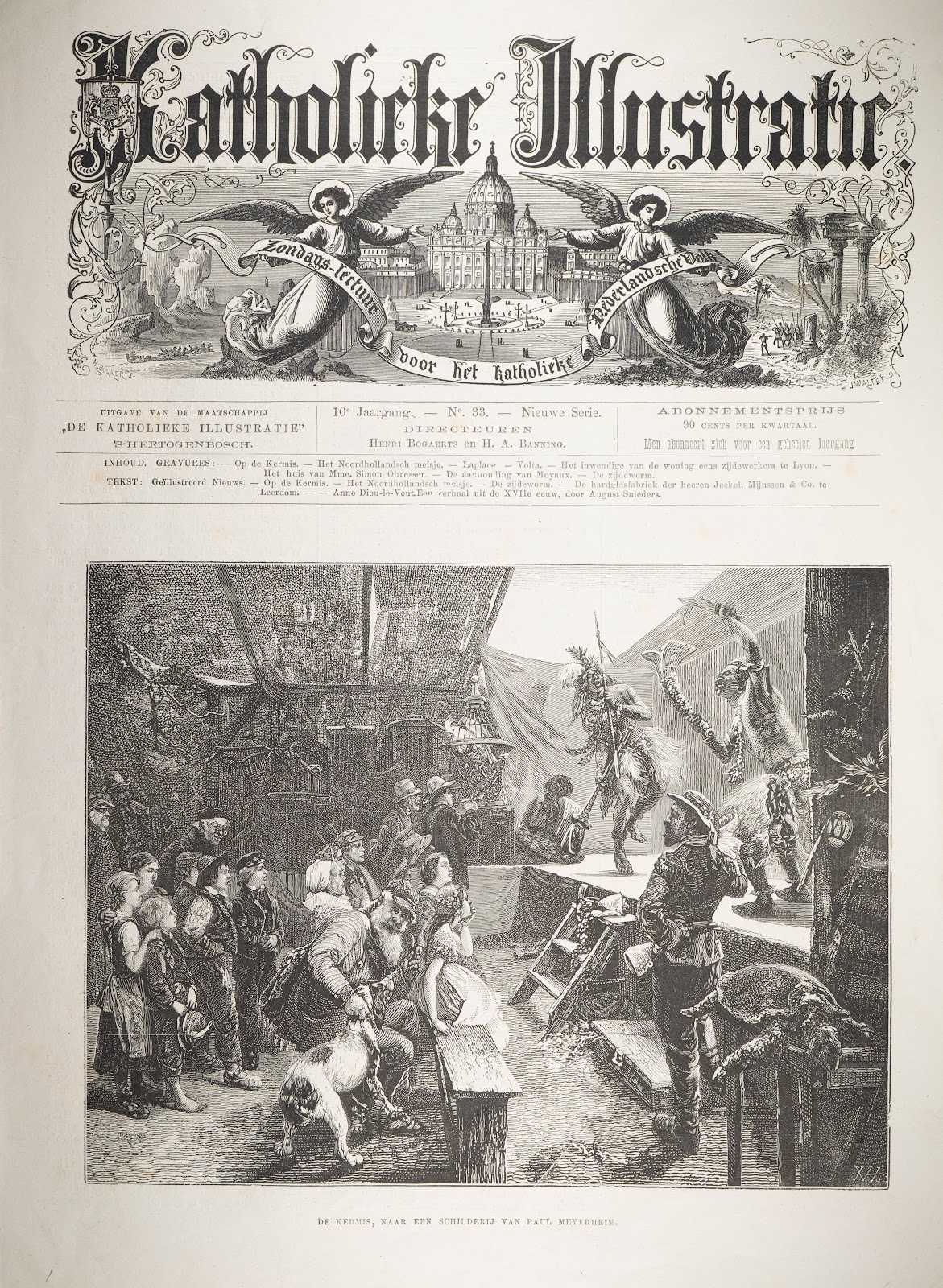

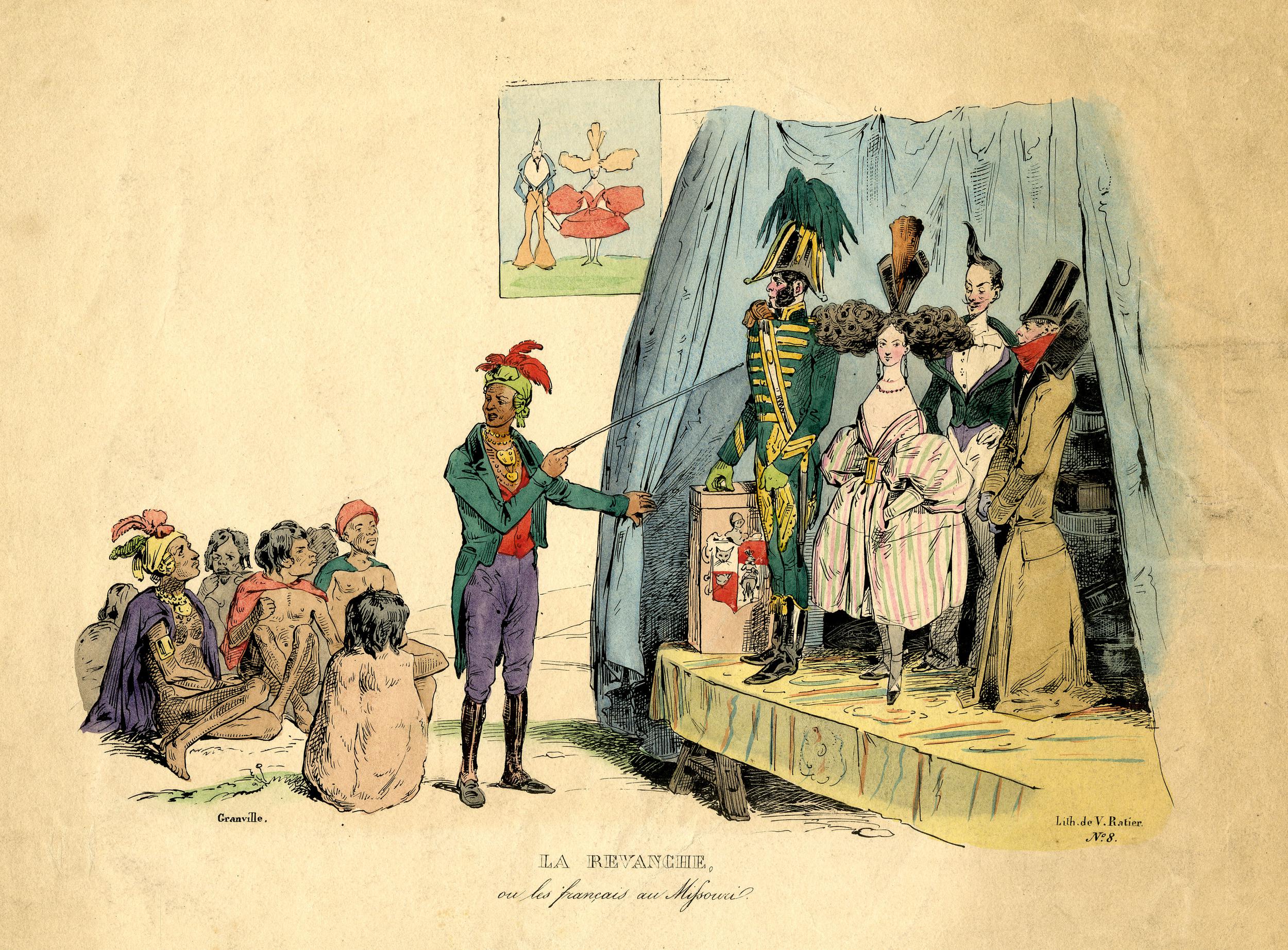

Exhibiting a so-called zoo humain had deep historical roots. Ever since the fifteenth century and during the transatlantic slave trade that followed, people from non-European cultures were forcibly transported to royal courts as novelties or diplomatic gifts. Chinese sailors also exhibited African residents in their homeland. The exhibition of people at the fair was part of a widespread show practice that responded to an insatiable craving for ‘curiosities’.

Although heavily criticized, especially in the first half of the nineteenth century, the practice exploded in the last decades of the nineteenth century. This was the direct result of increasing colonial trade. Showmen such as Carl Hagenbeck and P.T. Barnum cleverly capitalized on this interest. They built empires of ‘exotic’ animal and human trafficking, and in their wake a network of countless ‘impresarios’ emerged who travelled the world as managers of people from various colonies.

This ‘human spectacle’ could be seen at a range of locations: not only at the fairground or the zoo, but also at the circus, in bars, at the theatre, in popular museums, in amusement parks, and especially at the immensely popular universal, colonial, and regional exhibitions. The public was offered a fictitious view of ‘distant cultures’, which were often reduced to stereotypes that reinforced colonial ideas of superiority.

Related Sources

Grand théatre indien (Leaflet / poster, 1896)

Explore the database