Itinerant fair photographers: portraits for everyone

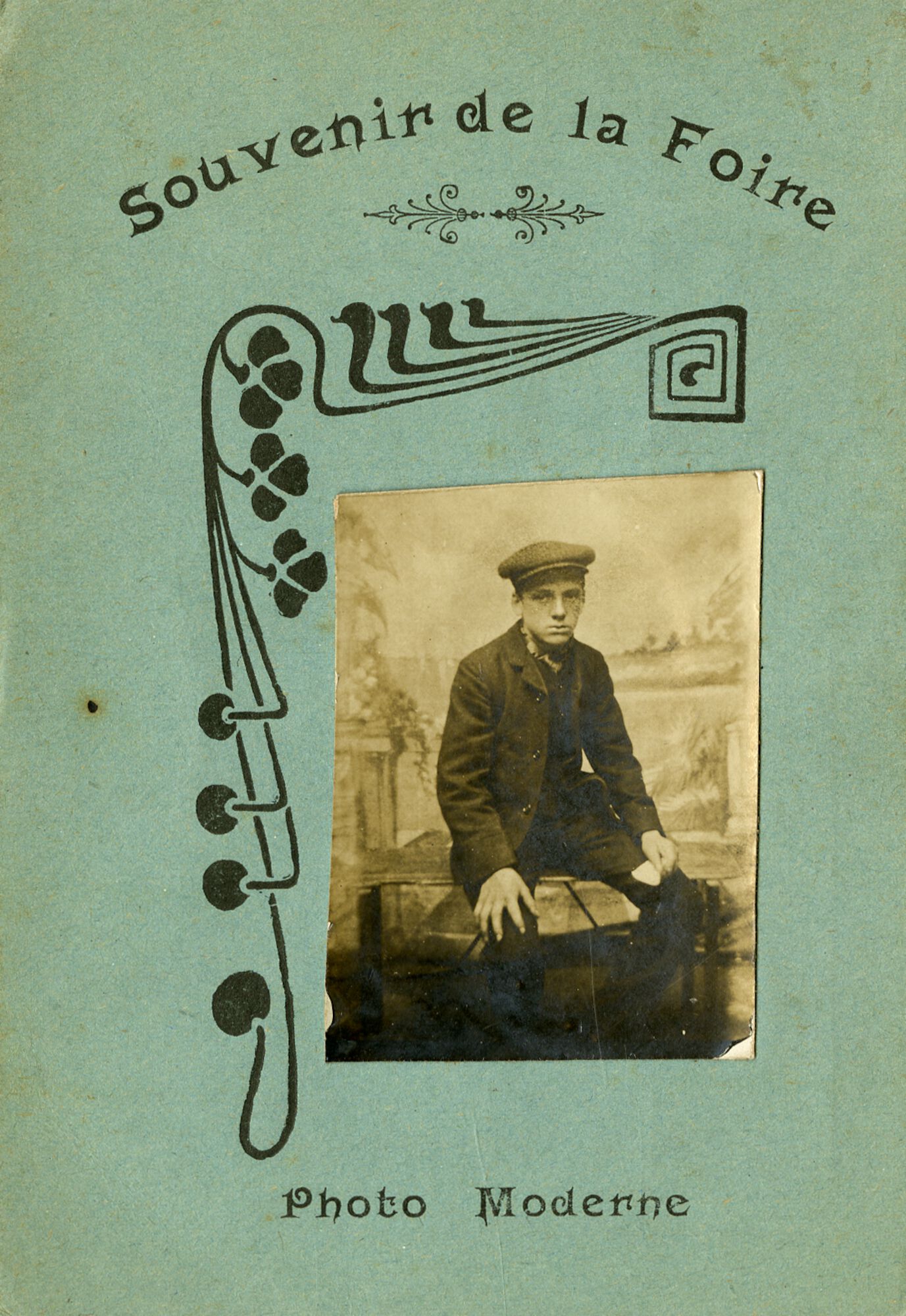

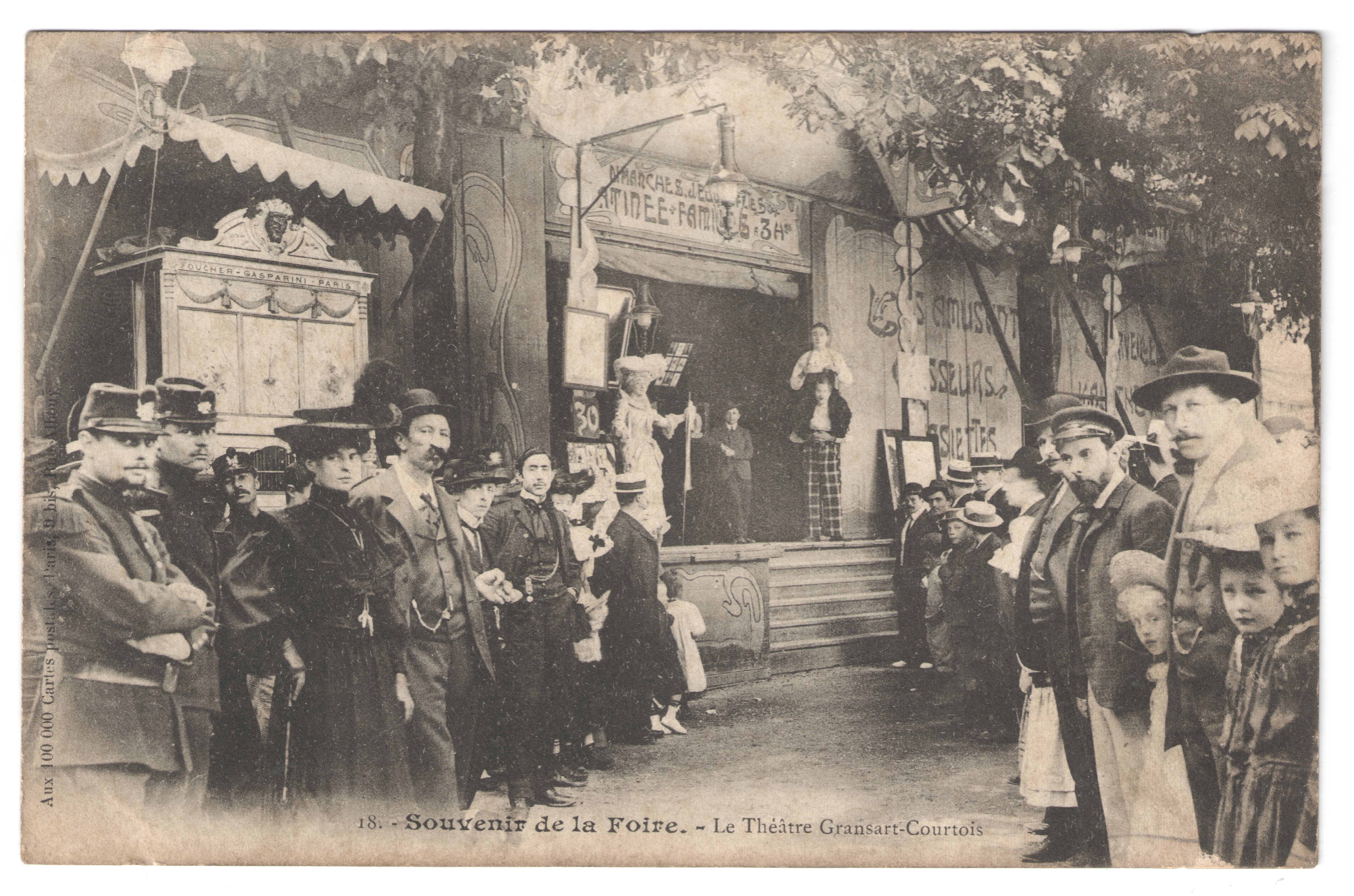

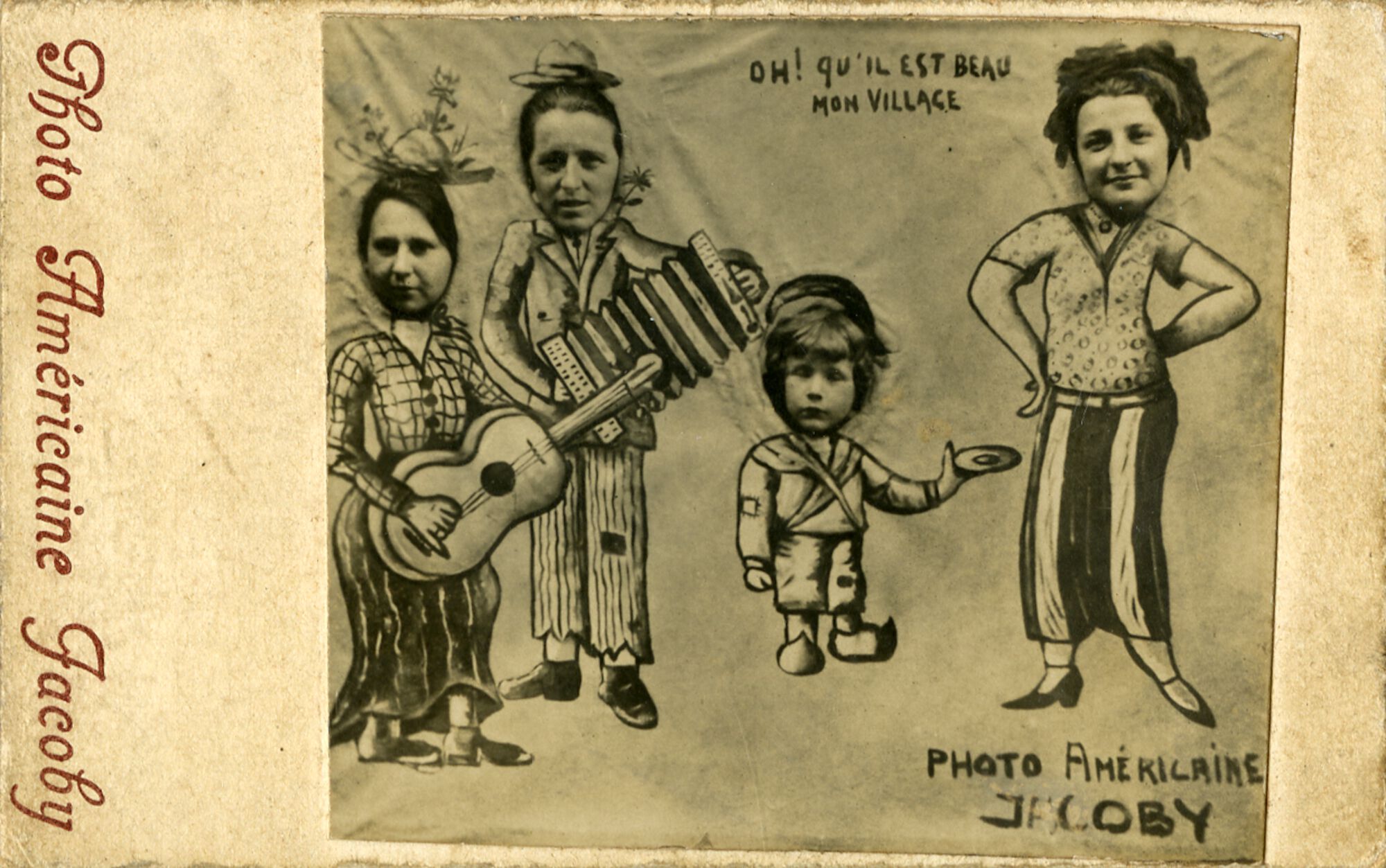

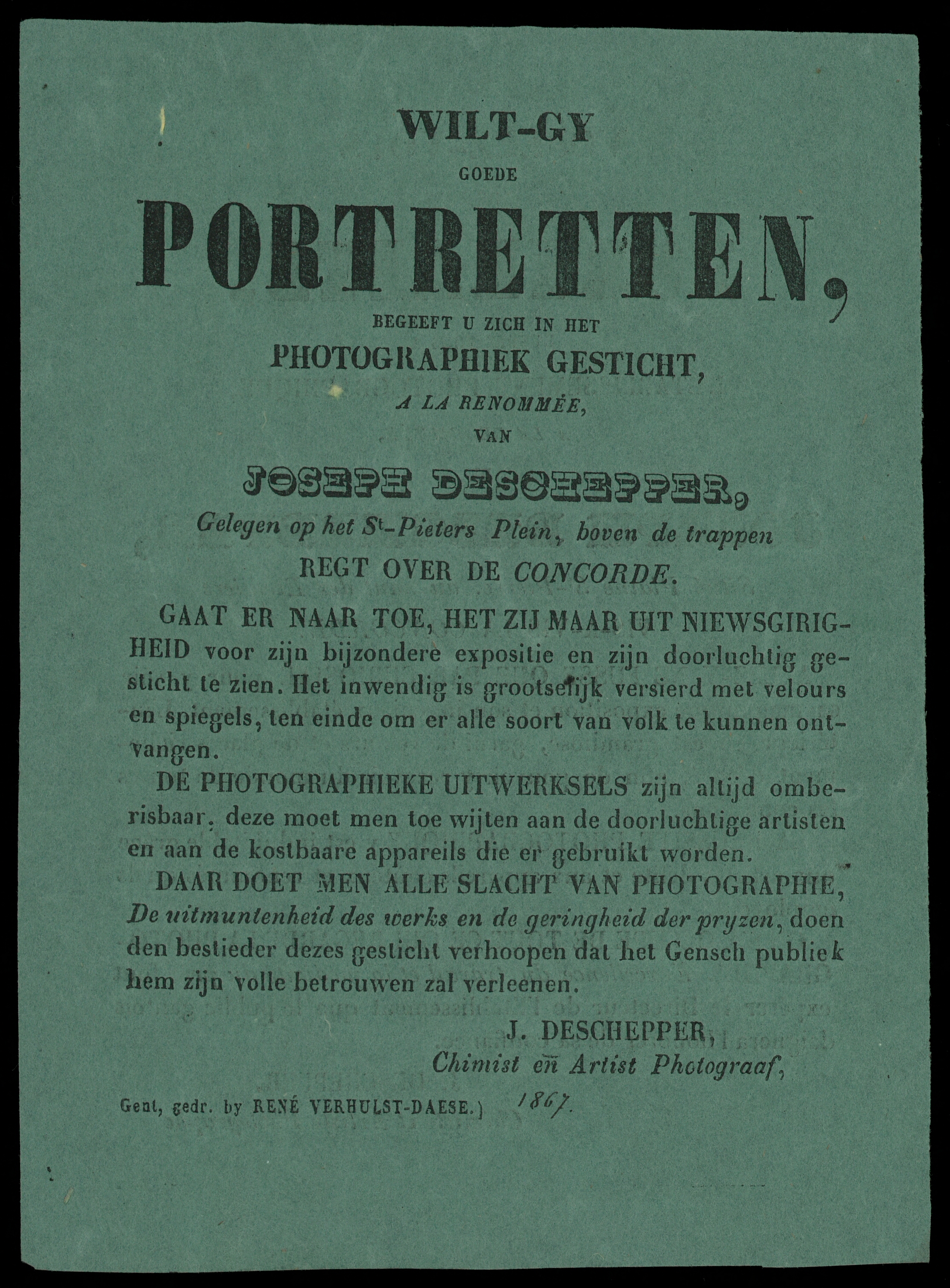

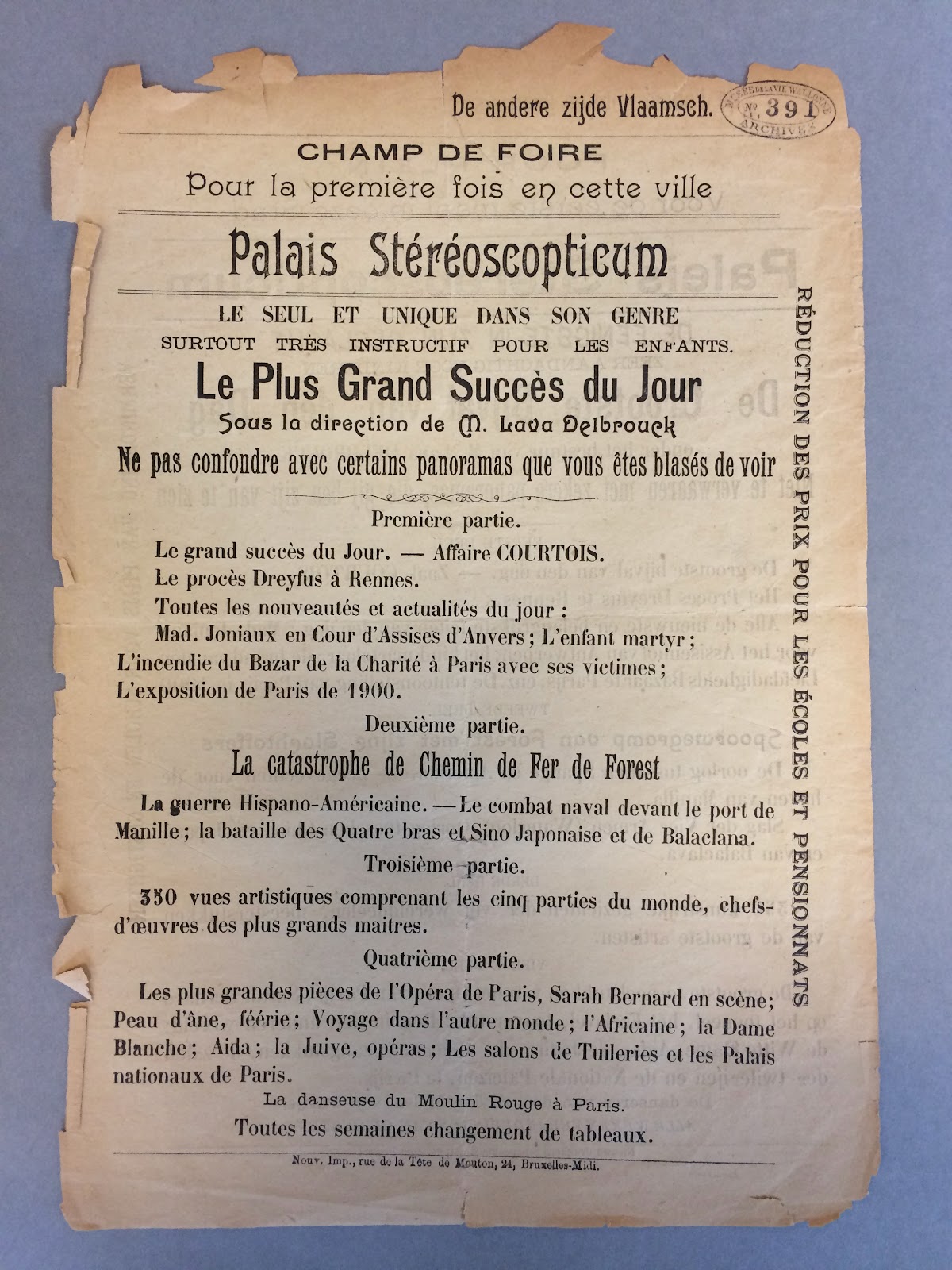

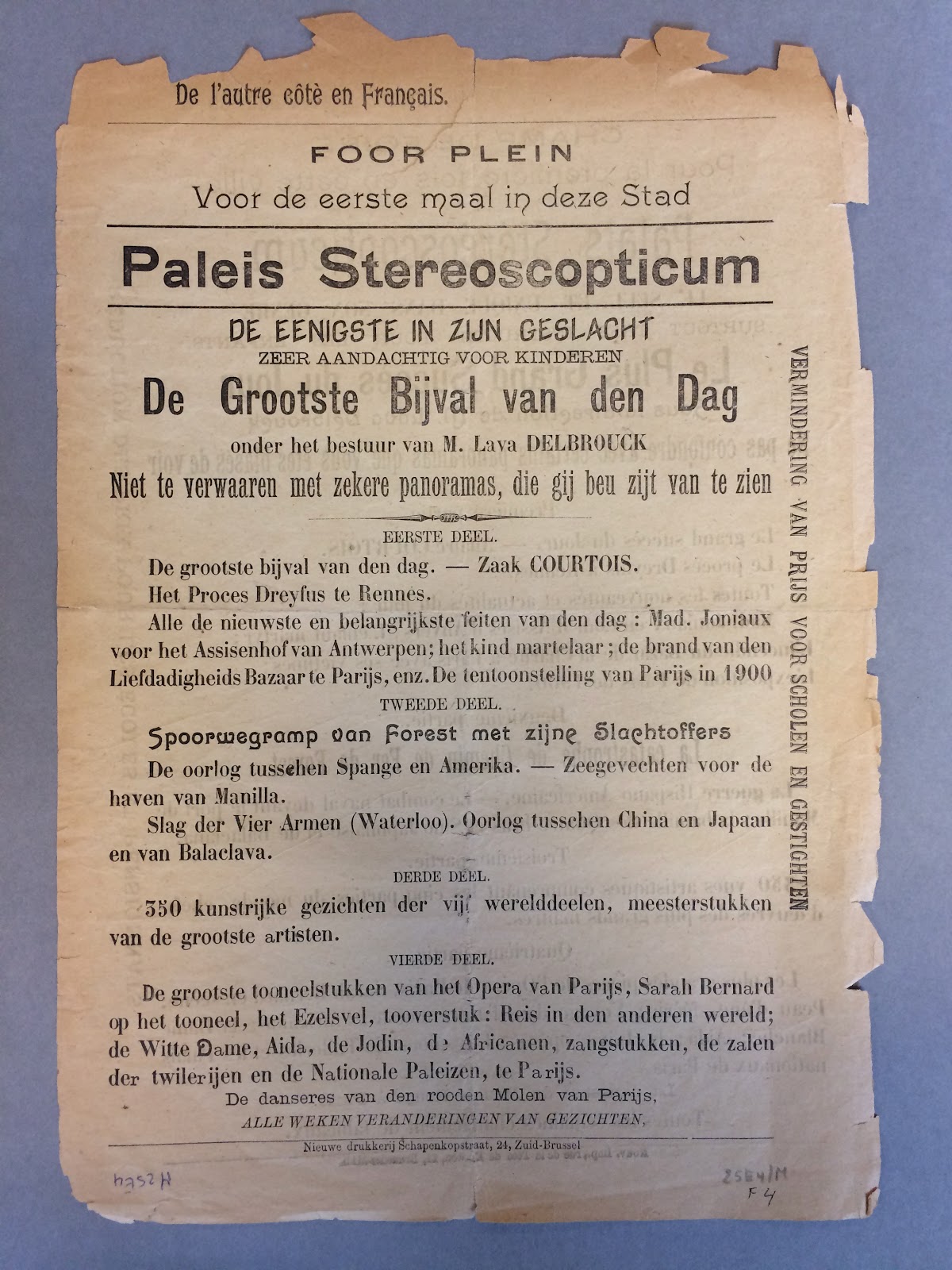

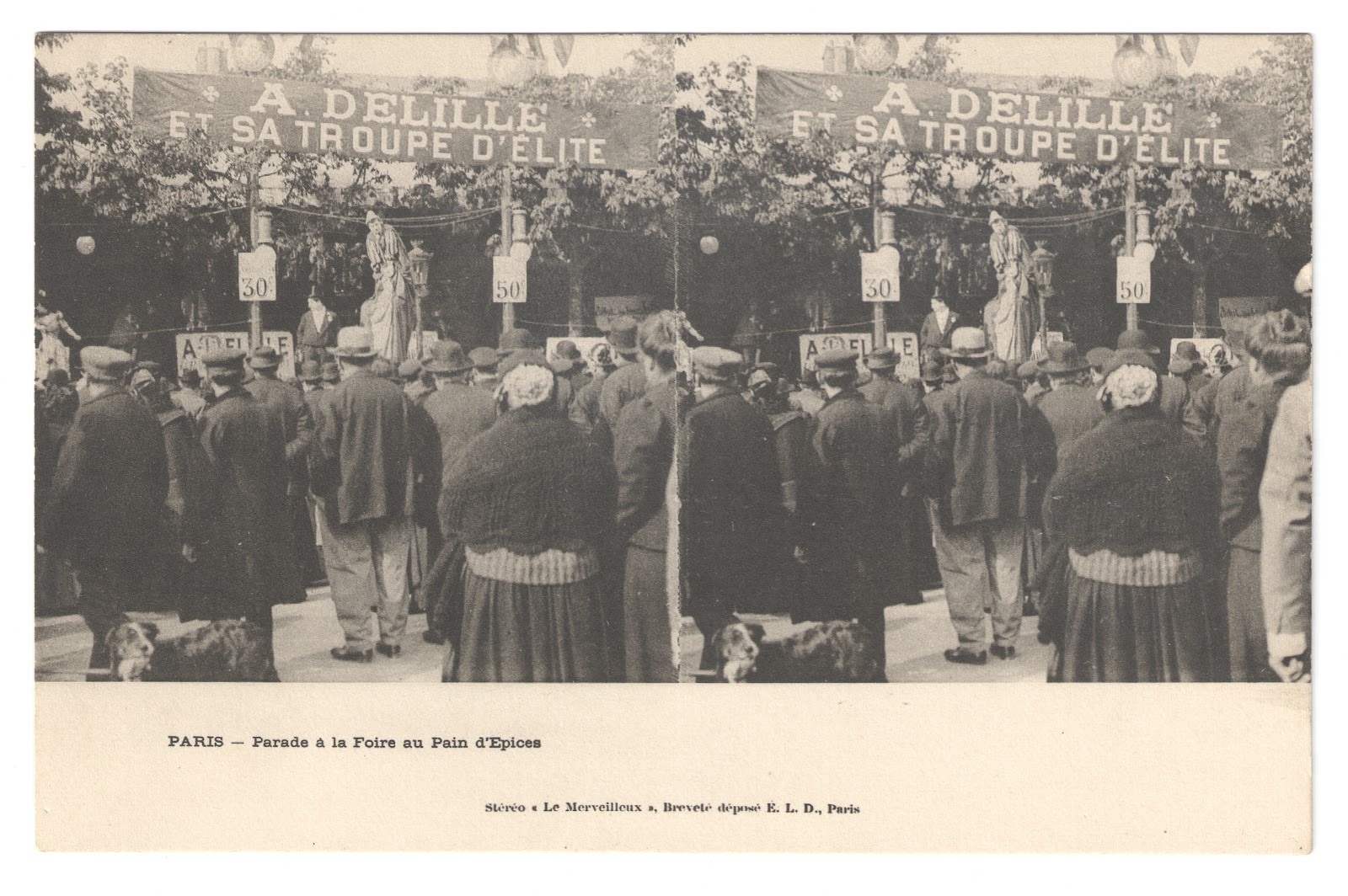

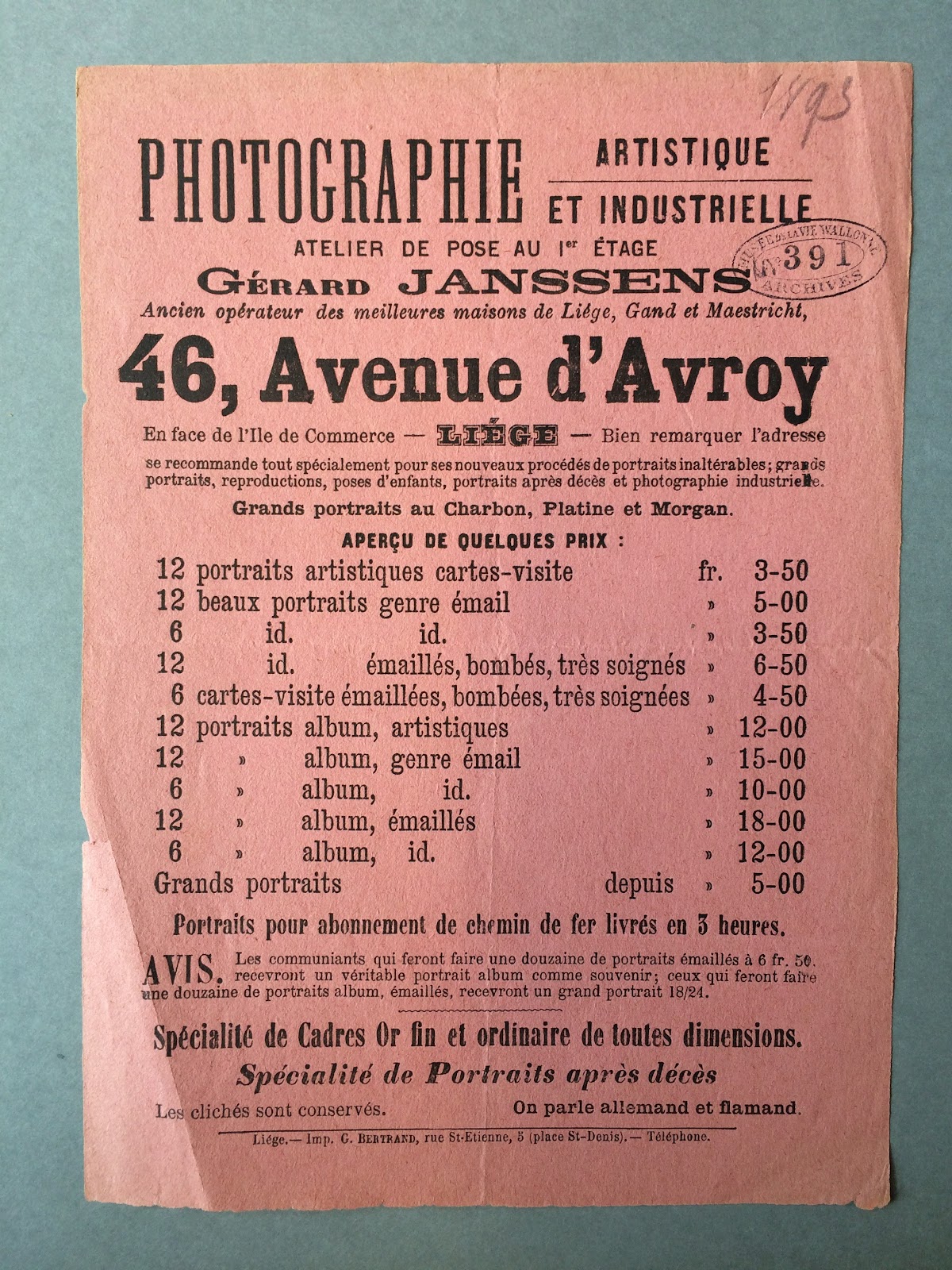

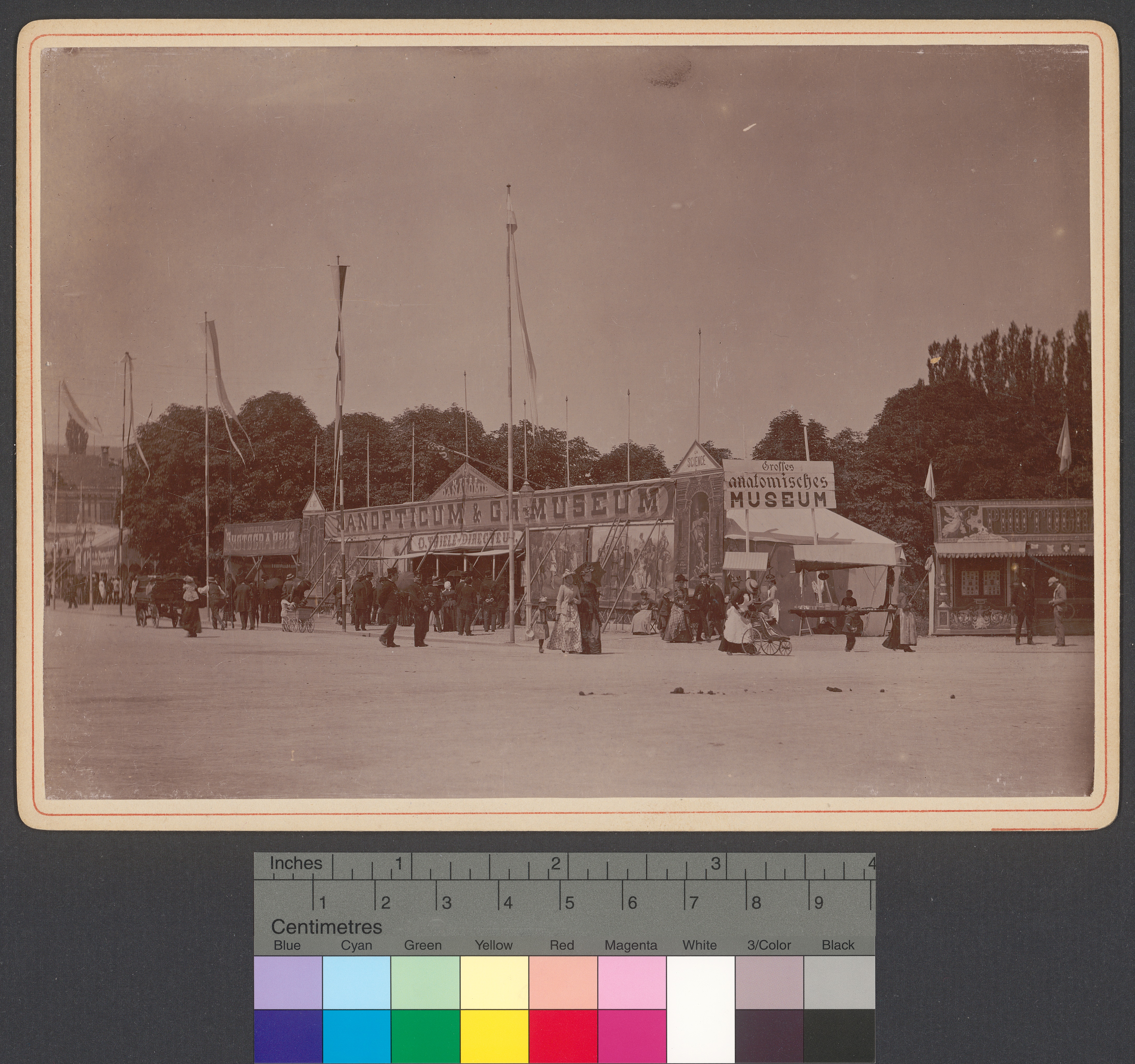

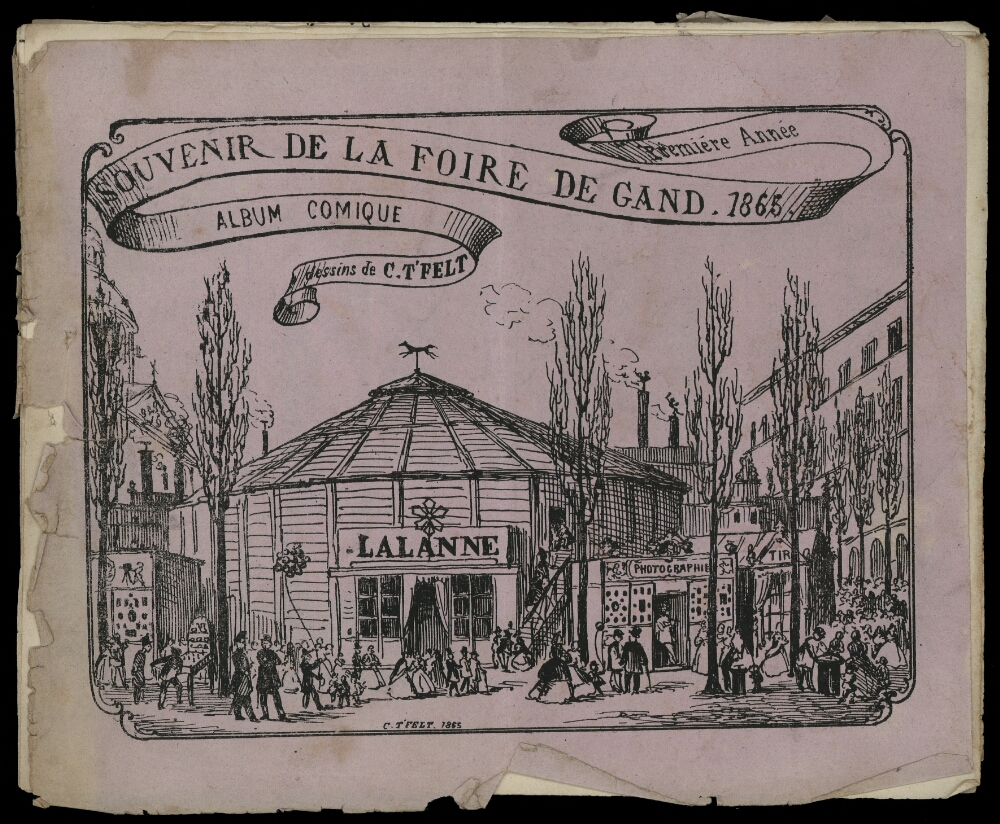

The photography barracks that first appeared at fairs from 1860 soon became one of the most visited attractions. They offered various techniques, such as ferrotyping, an early form of instant photography in which the image appeared directly as a positive on a metal plate. Although these early photographs were prone to rust and fading, their appeal was enormous. Photographers displayed their finest works on the facades of their barracks to tempt customers. Historical records show that the number of photographers present at the bigger fairs increased dramatically throughout the century. In Ghent, in the late nineteenth century, the city council granted licences to only eight photographers, while many more were active. Competition drove up the prices for stalls and forced photographers to stand out with new techniques and creative settings.

While the urban elite had their portraits taken in permanent studios, itinerant photographers offered an affordable alternative. In this way, they contributed to the democratization of the medium. The ferrotypes (or tintypes) are also called 'the photography of the poor' because they were cheaper than instant photos on glass. For people from out of town who only sporadically left their villages, the fair offered a great opportunity to have a portrait taken. For many, it was the first and only time they had their picture taken. An English correspondent wrote in 1898 that after a ride on the horse mill, the photo booth was always the next stop. Not only workers and peasants, but also factory girls in their Sunday clothes liked to be immortalized on a photograph.

Related Sources

Souvenir de la foire de Gand (Illustration)

Explore the database