Art, science, and progress!

Medicine enjoyed great social prestige from the early nineteenth century onwards. Through dissections, anatomy mapped the body and tried to unravel the secret of life. It transformed medicine from quackery and conjecture into a professional and scientific discipline. From 1850, the first large travelling anatomical cabinets appeared at the fairgrounds, converting public curiosity into a commercial enterprise.

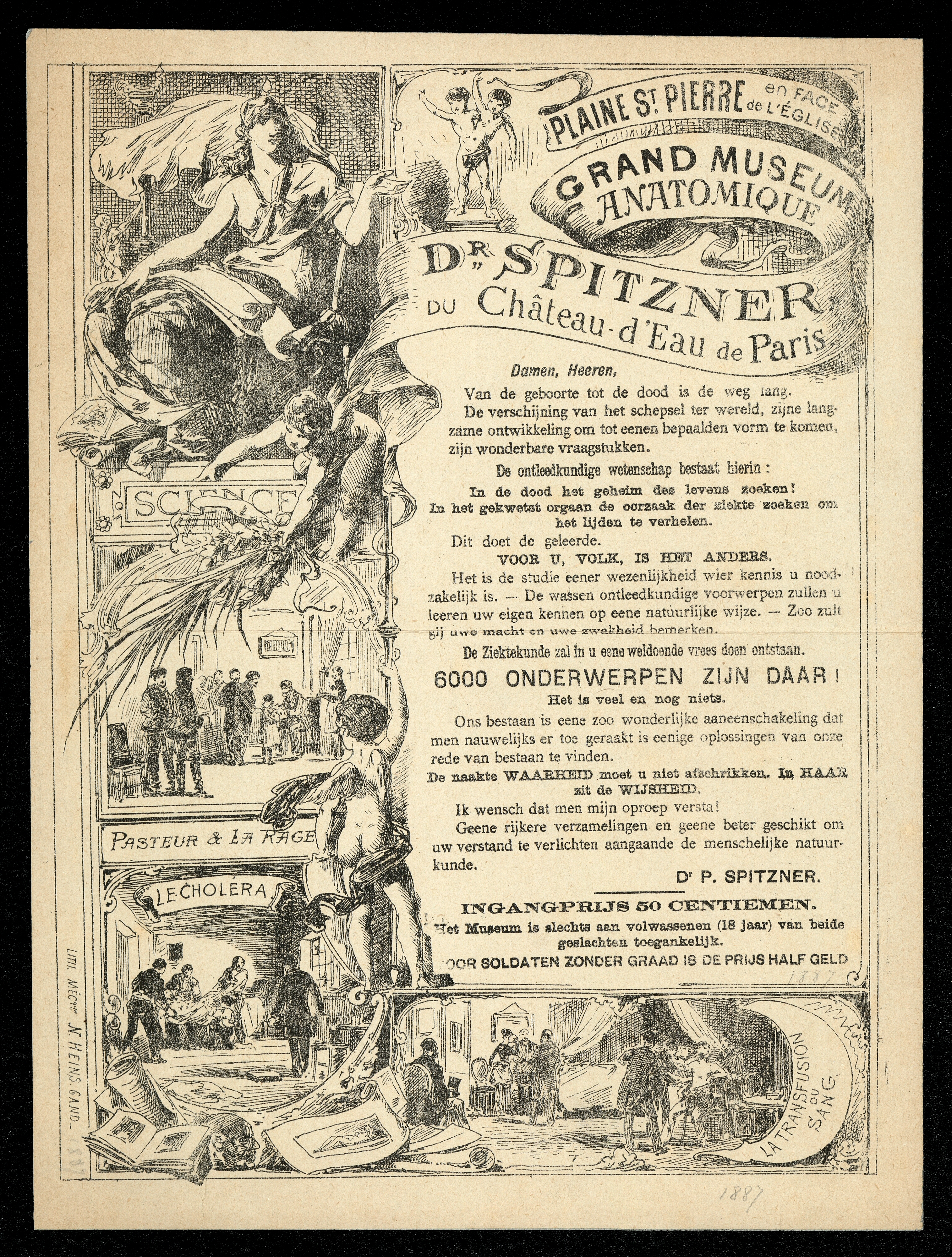

The German Pierre Spitzner founded his museum in France around 1870 and travelled with the exhibition. From 1878, he added Belgian fairs to his itinerary. Spitzner called himself 'doctor', but whether he had actually studied medicine is questionable. By using that title, he positioned himself as an expert who wanted to share his knowledge with the general public. Under his motto 'art, science and progress!', he preached the societal importance of medicine. Thanks to the arts, and especially wax models, Spitzner and his colleagues were able to convey medical knowledge in a comprehensible and aesthetic way.

From the eighteenth century onwards, anatomists had experimented with medical models in wax. Doctors saw these models as an alternative to studying real bodies, given the scarcity of human remains in medical schools. Soon, the artistic and lifelike models also aroused the interest of the general public. The versatility of wax allowed modellers to recreate realistic bodies, without the inevitable decay of real bodies. As dissection rooms and university cabinets increasingly became the exclusive domain of the scientist in the nineteenth century, travelling anatomy museums and wax models allowed the general public to learn about anatomy.

Related Sources

Anatomisch Museum dr. Kahn (Booklet / catalogue)

Explore the database

Musée anatomique de O. Thiele (Photo, 14-07-1890)

Explore the database

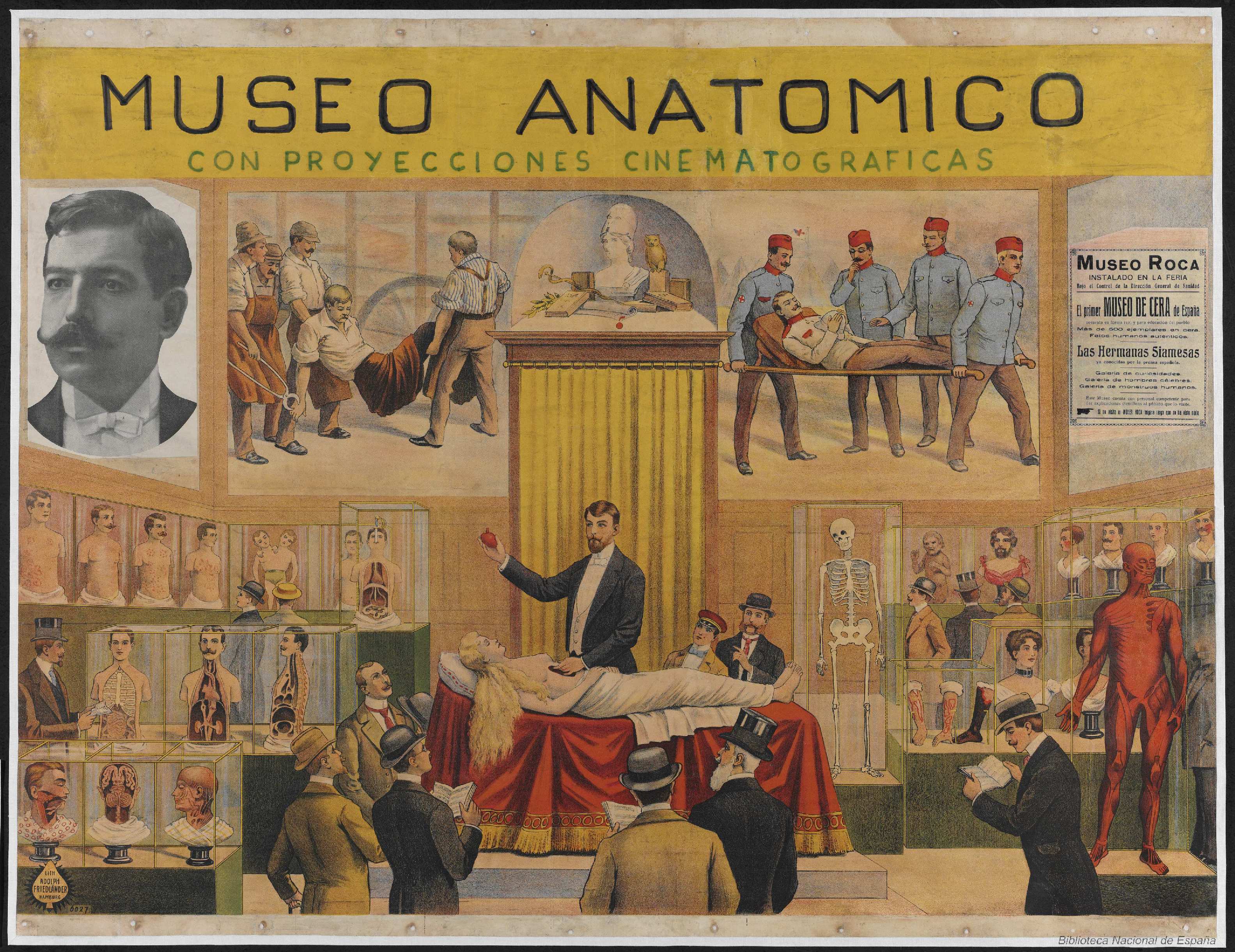

Museu Roca (Leaflet / poster, 1910)

Explore the database

Musée d'anatomie Spitzner (Leaflet / poster, 1887)

Explore the database