Occultism at the fair

An article published in the paper of the Belgian fairground union reported that in 1908 no fewer than 25 somnambules or 'sleepwalkers' — a common synonym at the time for fortune tellers and clairvoyants — were active at the Antwerp fair. Competition among these occult performers was fierce, especially at large urban fairs in cities like Ghent, Antwerp, and Bruges. To stand out amongst the many other fairground performers, fortune tellers had to find creative ways to distinguish themselves. They faced the dual challenge of promoting their talents and legitimizing their practices in an environment marked by both skepticism and fascination.

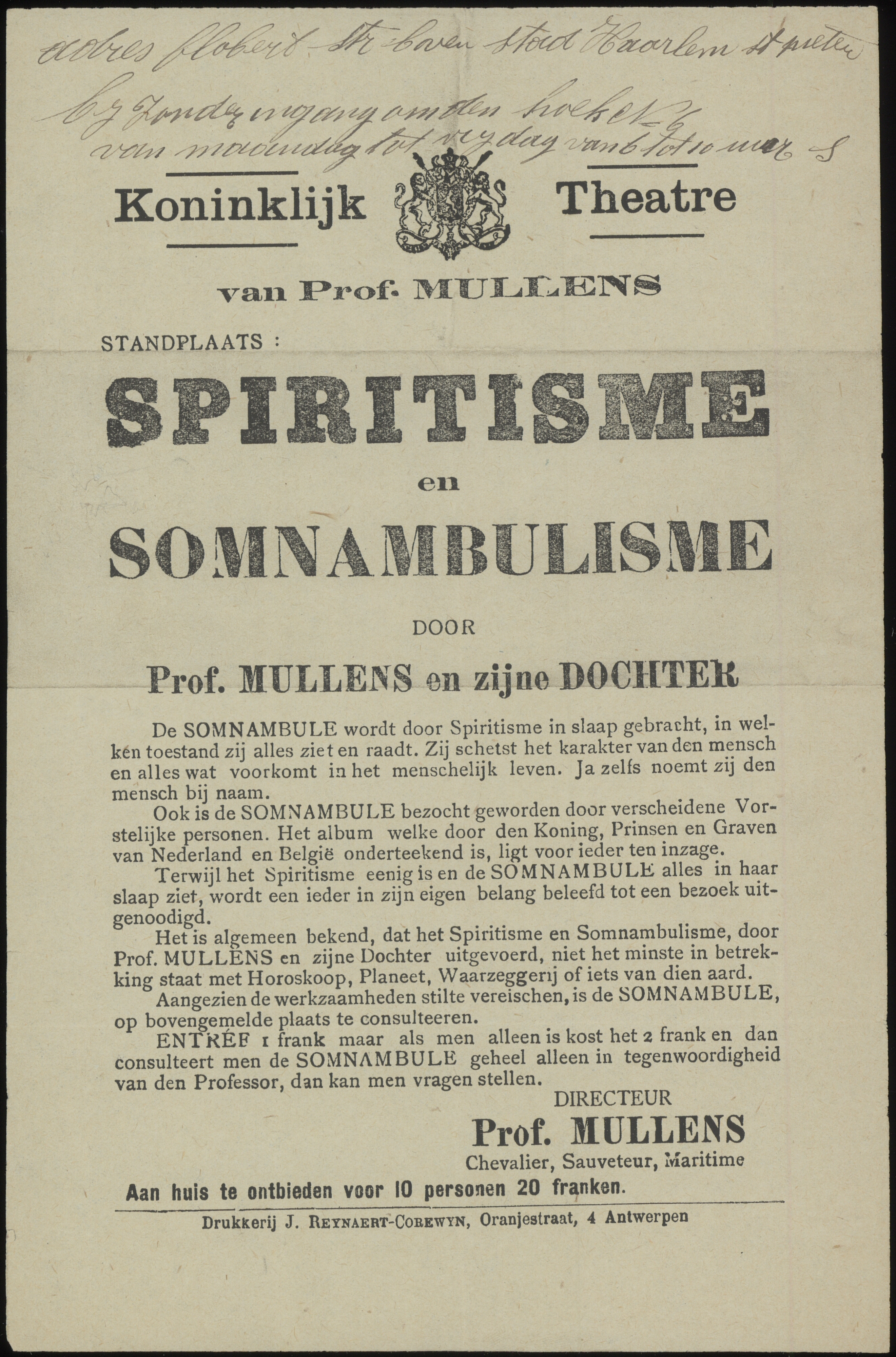

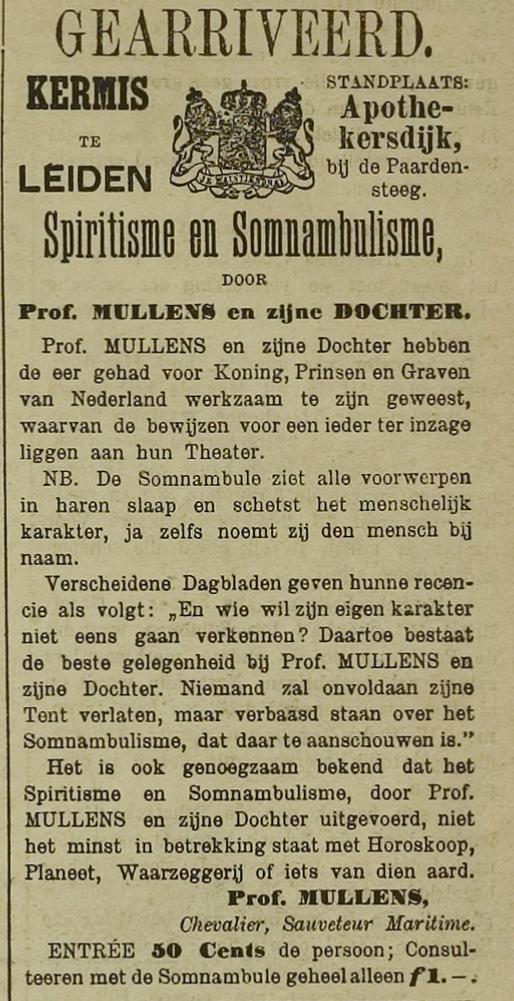

One recurring act on Flemish fairgrounds was the Dutch father-daughter duo Professor Mullens and his daughter. Hendricus Phillipus Mullens and his daughter Johanna Hendrika Mullens performed together in their so-called Royal Theatre and embraced a decidedly occult branding in their advertising. Their flyers sought to capture the public's attention with bold headlines proclaiming Spiritism and Somnambulism: terms carefully chosen to tap into the widespread interest in all things spiritual and supernatural.

Related Sources

Professor Mullens & dochter (Leaflet / poster, 1906)

Explore the database

Professor Mullens & dochter (Photo, 15-08-1910)

Explore the database

Professor Mullens & dochter (Leaflet / poster, 1889)

Explore the database