Mirrors and ghosts

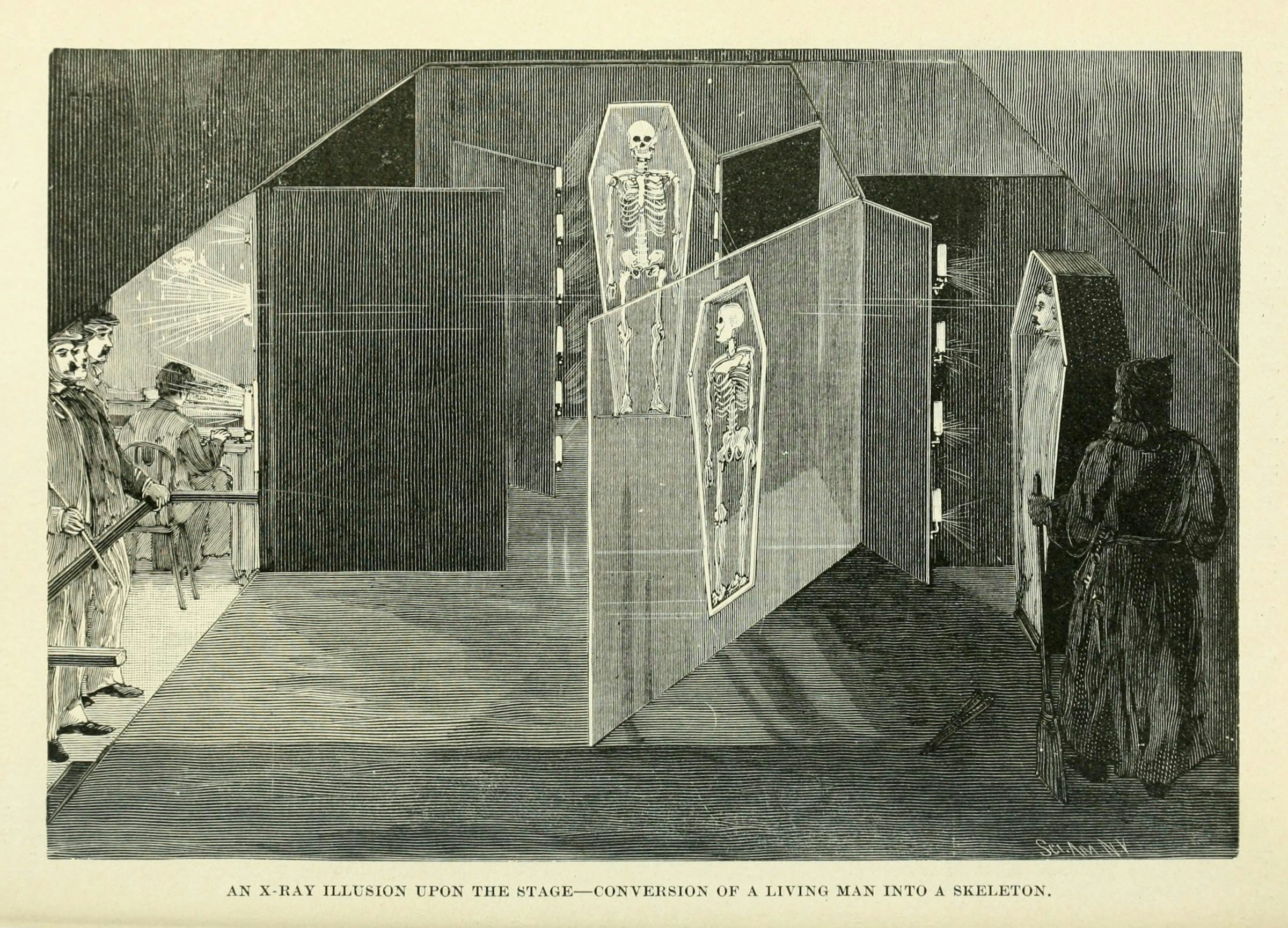

Manuals by late nineteenth-century illusionists and lighting technicians describe the illusion in detail. It appears to be the result of images reflecting off mirrors and morphing into one another. Behind the scenes, an ingenious game was played with light projected from different angles. To the viewer, it seemed as if the head itself was changing shape.

The interplay of alternating lighting on mirrors was a refined variation on the classic Pepper's Ghost by ‘Professor’ John Henry Pepper from 1862. The Brit was one of the first to conjure up a moving hologram in the theatre with the use of a magic lantern. A person under the stage – usually wrapped in a bright white sheet – was overexposed so that their reflection became visible via a slanted glass surface on the stage. The actors then interacted with that reflection, making it appear to the audience as if they were duelling with a ghost.

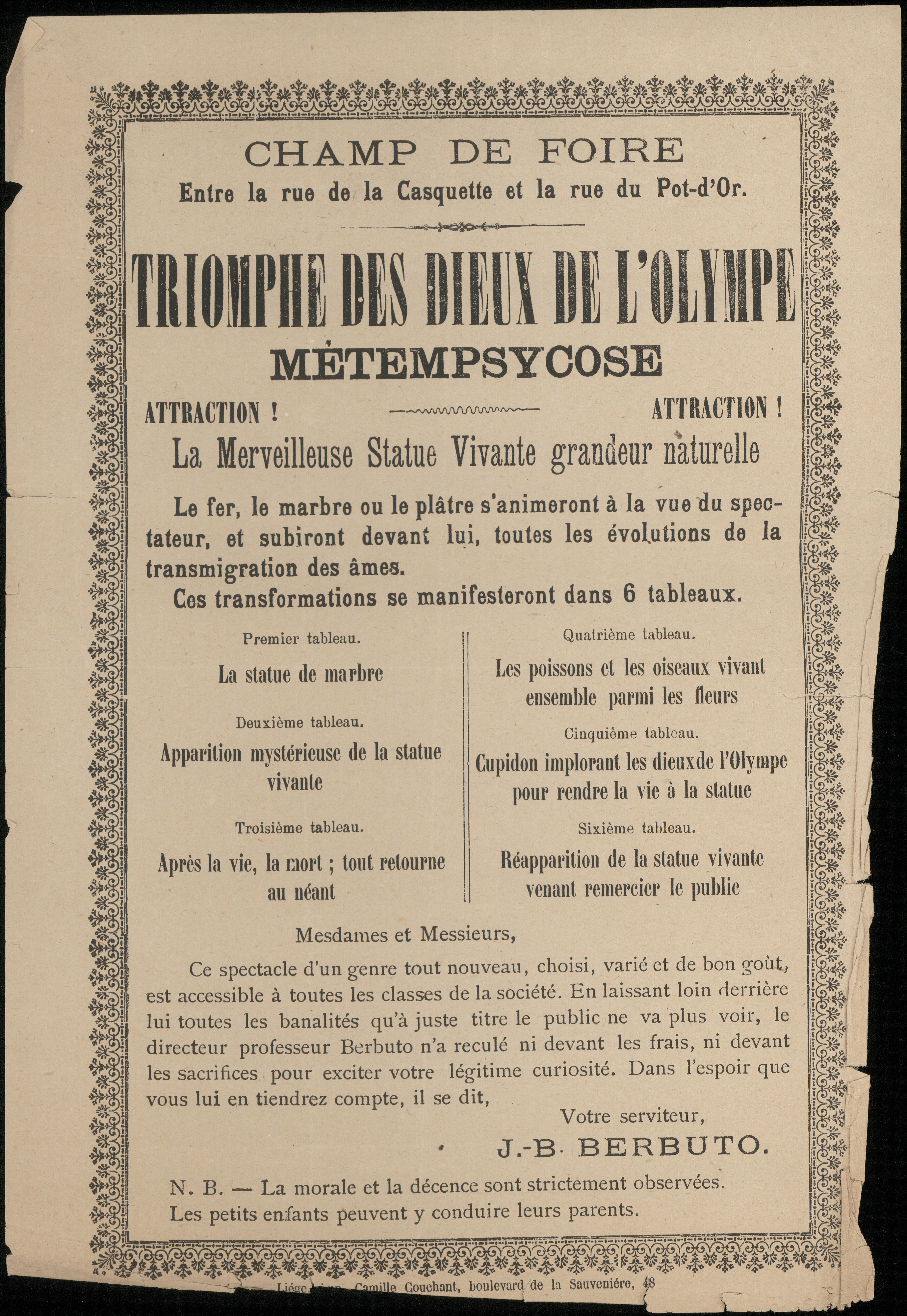

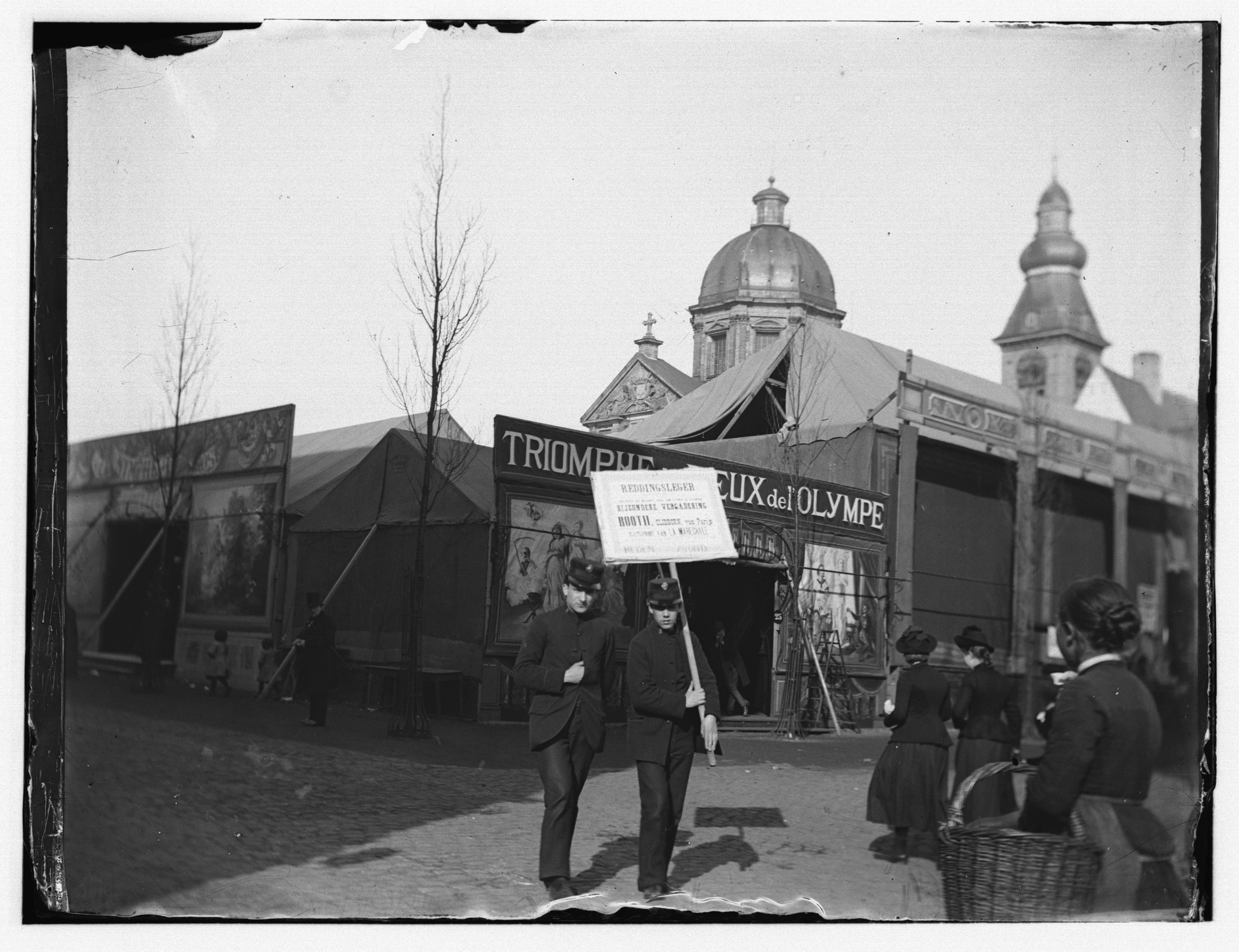

The Pepper’s Ghost act was hugely successful in the more famous theatres of Paris and London. Since the scenography consisted of large glass panels, it made the illusion both expensive and difficult to transport. Fairground operators succeeded in presenting a much more practical version with metempsychosis. Not only could they transport it over long distances, but they could also set it up at a fairground booth without much effort.

The metempsychosis illusion was in high demand. Technicians, producers, and artists competed for its performance and usage rights. A lawsuit between the well-known fairground illusionist Adrien Delille and Emile Voisin, a Parisian seller of magic tricks, made international headlines in 1887. Both parties accused the other of plagiarism. This shows that illusion was big business and an important source of income for many self-proclaimed fairground ‘professors’.

Related Sources

Le Triomphe des Dieux de l'Olympe (Photo, 1890)

Explore the database